The considered problems relate to any cognitive activity. Of particular importance for science is scientific knowledge, the specificity of which deserves special analysis.

Scientific and non-scientific knowledge

Cognition (and, accordingly, knowledge) can be divided into scientific and non-scientific, and the latter - into pre-scientific, ordinary and extra-scientific, or para-scientific.

Pre-scientific knowledge is a historical stage in the development of knowledge that precedes scientific knowledge. At this stage, some cognitive techniques, forms of sensory and rational cognition are formed, on the basis of which more developed types of cognitive activity are formed.

Ordinary and parascientific knowledge exist along with scientific.

Ordinary, or everyday, is called knowledge based on the observation and practical development of nature, on the life experience accumulated by many generations. Without denying science, it does not use its means - methods, language, categorical apparatus, however, it gives certain knowledge about the observed natural phenomena, moral relations, principles of education, etc. A special group of everyday knowledge is the so-called folk sciences: folk medicine, meteorology, pedagogy, etc. Mastering this knowledge requires a lot of training and considerable experience, they contain practically useful, time-tested knowledge, but these are not sciences in the full sense of the word.

Extra-scientific (para-scientific) includes knowledge that claims to be scientific, uses scientific terminology, and is incompatible with science. These are the so-called occult sciences: alchemy, astrology, magic, etc. Having arisen in the era of late antiquity and developed in the Middle Ages, they have not disappeared even now, despite the development and dissemination of scientific knowledge. Moreover, at the critical stages of social development, when the general crisis is accompanied by a spiritual crisis, there is a revival of occultism, a departure from the rational to the irrational. Belief in sorcerers, palmists, astrological forecasts, in the possibility of communicating with the souls of the dead (spiritualism) and similar "miracles" is being revived. Religious and mystical teachings are widely spread.

So it was during the years of the crisis generated by the First World War, when the “theory of psychotransmutation” by G.Yu. Godzhieva, anthroposophy R. Steiner, theosophy E.P. Blavatsky and teachings. In the 60s. during the crisis in the countries of the West, esoteric teachings turned out to be fashionable (from the Greek - “directed inwards”. Knowledge intended only for the “chosen ones”, understandable only to them.).

The crisis in our country, generated by the perestroika processes, has created a spiritual vacuum, which is being filled by all sorts of ideas and "teachings" that are far from science. The existence of non-scientific ideas along with scientific ones is due not least to the fact that scientific knowledge cannot yet answer all the questions in which people are interested. Biology, medicine, agricultural and other sciences have not yet discovered ways to prolong a person's life, get rid of diseases, protect him from the destructive forces of nature, crop failure, etc. People hope to find simple and reliable means of curing diseases and solving other vital problems. These hopes are supported by some sensationalized media. Suffice it to recall the speeches on radio and television of psychics and psychotherapists or the "charged" issue of newspapers, "healing" from all diseases. And many people turned out to be receptive to these and similar “miracles”.

It cannot be denied that some parascientific theories contain elements of useful knowledge that deserve attention. The futile attempts of alchemists to find a "philosopher's stone" for the transformation of base metals into gold and silver were associated with the study of the properties of metals, which played a certain role in the formation of chemistry as a science. Parapsychology, exploring forms of sensitivity that provide ways of receiving information that cannot be explained by the activity of known sense organs, forms of influence of one living being on another, accumulates material that can receive further scientific justification.

However, the search for superintelligent means of cognition, supernatural forces, irrationalism and mysticism are not compatible with scientific knowledge, with science, which is the highest form of cognition and knowledge.

Science arose as a result of dissociation from mythology and religion, from the explanation of phenomena by supernatural causes. It relies on a rational explanation of reality, rejecting faith in superintelligent means of knowledge - mystical intuition, revelation, etc.

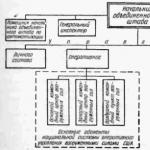

Science is a sphere of research activity aimed at the production of knowledge about nature, society, and man. Along with scientists with their knowledge and abilities, qualifications and experience, it includes scientific institutions with their experimental equipment and instruments, with the total amount of knowledge achieved, methods of scientific knowledge, conceptual and categorical apparatus.

Modern science has powerful material and intellectual means of cognition; it not only opposes various non-scientific teachings, but also differs from ordinary cognition.

These differences are as follows.

The object of everyday knowledge is predominantly observable phenomena, and the knowledge gained is a collection of information that is not given in the system, they are not always justified and often coexist with obsolete prejudices. Scientific knowledge deals not only with observable, but also with unobservable objects (elementary particle, gene, etc.). It is characterized by consistency, systematicity, the desire to substantiate its provisions with laws, special methods of verification (scientific experiment, rules of inferential knowledge).

The purpose of ordinary knowledge is limited mainly by immediate practical tasks, it is not able to penetrate into the essence of phenomena, discover laws, form theories. Scientific knowledge poses and solves fundamental problems, puts forward well-founded hypotheses, and develops long-term forecasts. Its goal is the discovery of the laws of nature, society, thinking, knowledge of the essence of phenomena, the creation of scientific theories.

The means of everyday knowledge are limited by the natural cognitive abilities that a person has: the sense organs, thinking, forms of natural language, relies on common sense, elementary generalizations, and the simplest cognitive techniques. Scientific knowledge also uses scientific equipment, special research methods, creates and uses artificial languages, special scientific terminology.

Science differs from other types of knowledge (ordinary, religious, artistic, ideological) in the following characteristics:

a) By subject. The subject of science is not all the infinitely diverse connections and phenomena of the world, but only essential, necessary, general, recurring connections - laws. A scientist in the midst of suddenness is looking for necessity, in single, concrete facts - the general.

b) According to the method. In science, special methods and techniques of cognition are developed - methods. In the system of science, disciplines are being developed that are specifically involved in the study of methods of cognition: methodology, logic, history of science, linguistics, computer science, etc. Logic is the science of generally valid forms and means of thought necessary for rational cognition. Methodology - the doctrine of the methods of cognition, the principles and limits of the application of methods, their relationship (system of methods). General principles of knowledge and general scientific methods are traditionally studied in philosophy. Any developed science is characterized by methodological reflection, that is, substantiation and systematization of its own research methods. Modern natural science and scientific and technical knowledge are characterized by the widespread use special tools and devices (there is even the concept of "industry of science"). The methods of science are divided into philosophical (metaphysical, dialectical, the principle of general connection, the principle of historicism, the principle of contradiction, etc.), general scientific and specifically scientific, as well as empirical and theoretical (See Table 6).

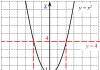

c) language. Science creates and uses a specific language. Language is a system of signs that serves as a means of human communication, thinking and expression. Language is a specific means of conveying information. There are natural and artificial languages. The unit of natural language is the word. As part of artificial languages - the process of formalization. Formalization is the procedure for replacing the designation of a real object or its verbal description with a sign. For example, the same phenomenon expressed in natural language (three plus two equals five) and formalized language (3 + 2 = 5). Formalized languages of science contribute to the brevity, clarity of expression of thought, avoid ambiguity, carry out complex operations with iconic object models. Education (especially the humanities) is also used in natural language, but even here there are special requirements: consistency, rigor, and clarity in the definition of terms. In science, the process of international unification of the language is gradually going on. Mathematicians or cyberneticians from different countries today do not need a translator, they understand each other thanks to universal formalized languages. Obviously, representatives of all other sciences will follow them. According to the results. Scientific knowledge is systematic, substantiated, proven and presented in the form of specific forms. The main forms of scientific knowledge are an idea, a problem, a hypothesis, a scientific law, a concept, a scientific picture of the world.

e) By subject. Scientific activity presupposes a special preparation of the subject. A scientist must have certain qualities: S broad erudition; S deep knowledge in their field; S ability to use scientific methods; S creativity;

v a certain system of goals and value orientations

(truth is the top of the scientist's hierarchy of values) S strong will.

In scientific knowledge, as a rule, empirical and theoretical levels are distinguished. Comparative analysis of them will be presented in the form of a table (see table 6).

Table 6. Empirical and theoretical levels of scientific knowledge.

The differences presented are, of course, not absolute. In real scientific activity, empiricism and theory are inextricably linked and complement each other.

Enrich your vocabulary with the following concepts: cognition, object of cognition, subject of cognition, image, objectivity of the image, subjectivity, resentment, agnosticism, sensory cognition, sensation, perception, representation, sensationalism, rationalism, abstraction, concept, judgment, conclusion, truth, dogmatism, relativism, scientific knowledge, method of cognition, concrete, abstract, observation, measurement, description, experiment, analysis, synthesis, induction, deduction, analogy, hypothesis, idealization.

Do the following creative exercises:

Exercise 1

Which epistemological position is expressed in the following fragment of a poetic text: "comprehension of the universe, Know everything, and not selecting: What is inside, you will find in the outside; What is outside, you will find inside. So accept the intelligible riddles without looking back at the World."

Task 2

What is the name of the philosophical direction, reflected in the following thesis: "The knowledge of a person never achieves more than the feelings give him. Everything that is inaccessible to the senses is also inaccessible to the mind." K. Helvetius.

Task 4

Which epistemological position is accounted for by the philosopher: "All thoughts and actions of our soul stem from its own essence and cannot be known to it ... feelings." G. Leibniz.

Task 5

Describe the position of agnosticism, provide arguments or examples to prove the thesis: "The world is unknowable."

Task 6

How do you understand the reasoning of F. Bacon: "Empiricists, like ants, only collect and are content with what they have collected. Rationalists, like a spider, make fabric from themselves. The bee chooses the middle way: it collects material from garden and wild flowers, but arranges and changes it in his skill, the real work of philosophy does not differ from this. F. Bacon.

Task 7

How can one answer the question from different epistemological positions: is it given to a person when he sees red, feels solid, etc., is it an objective reality or not?

Task 8

What arguments can you give to substantiate the thesis: "The world is recognizable." How to combine with this statement the well-known paradox of the process of cognition, the more we know, the greater the limit of the unknown.

Task 9

It has been proven that in nature there is no red, green, yellow ... Why do we all define colors the same?

Task 10

Which epistemological position is reflected in the following reasoning: "Since external objects, as they appear by feeling, do not give us, through their operations in individual cases, the idea of force, or the necessary connection, let's see if it is not our own spirit and whether it is NOT copied by any inner impression?" D. Yum.

How does the visual image of an object in the mind differ from a photograph? Which image is more accurate, adequately reflects the object? Justify your answer.

If the world around us is contradictory, then its knowledge must be contradictory, only in this case it will be true. Does it follow from this that consistent knowledge is a mistake?

The world is in constant change, movement, development: we strive to present the results of the knowledge of the developing world in complete, statistical positions - truths. How is this contradiction resolved in various epistemological concepts?

Analyze the epistemological position of the philosopher: "I see this cherry, I perceive it by touch, I taste it ... So, it is real. Remove the feeling of softness, moisture, redness, astringency - and you will destroy the cherry. Because it is not a being, different from sensations, then cherry ... is nothing but a combination of sensory impressions or ideas perceived by different senses. J. Berkeley.

After all, you create the mind

And it can even inhabit the planets of creation, brighter than all living, And give them the image of a durable raft. ... Immensely thought,

After all, a drowsy thought Holds years, Condenses long life into one time.

D.J. Byron

What characteristic feature of thinking is noted here? How is this feature interpreted in various epistemological concepts?

"Truth is that which simplifies the world, not that which creates chaos." A. de Saint-Exupery.

What feature of true knowledge is noticed here? What interpretations of truth do you know?

Define the term "objective truth". If all people disappear and only books remain on the "bare" Earth, will truths remain?

Justify your answer.

Opposite epistemological positions are confronted by M. Gorky in the following text: "... In everything, the Meshchanin makes the existence of a person useful or amusing for himself. He likes to have strong, comfortable furniture in his house, and strong, reliable truths in his head, according to which he could well hide himself from the onslaught of new trends of thought. And therefore he is always in a hurry to make bold conjectures. For a person, something useful for his life - it is his work of life - is due to such a mass of errors and prejudices, which he considers to be truths of tested strength It is much more convenient for him to believe - he wants to live in peace - and he does not like to think, because Opinion tirelessly seeks and creates, explores what it has created and - destroys, and creates again. " M. Gorky.

"And what measure of truth can be clearer and more certain than the true idea itself? As light reveals both itself and the surrounding darkness, so truth is the measure of both itself and falsehood." B. Spinoza.

Do you agree with the philosopher? What are the criteria for true knowledge?

"It should not be forgotten that the criterion of practice can never, by its very nature, confirm or refute completely any human idea." VLenin

Practice is both an absolute and a relative criterion of truth. Explain this thesis.

They say that the English scientist DzhThomson, who discovered the electron in 1897, was confused and even amazed by what he found, because he could not believe in the existence of bodies that would be smaller than an atom. Not without hesitation, they gave him the first speeches to colleagues and the first publications, especially since they received his message, to put it mildly, without enthusiasm. Give a philosophical commentary on this historical fact.

“What is true is absolutely true in itself, the truth is identically one, people or monsters, angels or gods perceive it in judgments ... Even if all the masses subject to attraction disappeared, the law of attraction would not be destroyed, but simply remained limits of possible application. £ Husserl.

Analyze the epistemological position of the author.

Do you agree with A. Poincaré's subsequent remark about "unusual" geometries: "The more these constructions move away from the most ordinary concepts and, consequently, from nature

the more clearly we see what the human mind can do when it is freed more and more by the tyranny of the outside world."

Analyze the following statement by M. Born: "Observation or measurement does not refer to the phenomenon of nature as such, but only to the aspect under which it is considered in frames of reference, or to projections onto the frame of reference, which, of course, is created by the entire applied installation ".

What geoseological problems are reflected in the following reasoning by E. Mach: "In ordinary thinking and in everyday speech of course, they oppose the apparent, the illusory to reality. Holding a pencil in front of us in the air, we see it in a straight position; lowering it in an inclined position into the water, we see it bent. In the latter case, they say: "The pencil seems to be curved, but in reality it is straight." To speak of an illusion in such cases makes sense from a practical point of view, but not from a scientific point of view. To the same extent, it makes no sense ... the often discussed question is there really a world, or is it just an illusion ... ".

What contradiction of the process of cognition is referred to in the following statement: "Dialectics - as Hegel explained - includes the moment of relativism, negation, skepticism, but is not reduced to relativism"? V. Lenin.

What feature of the process of cognition is noticed in the following statement: “Both day and night the sun walks before us, but the stubborn Galileo is right!”?

What feature of knowledge did F. Bacon pay attention to, arguing that Truth is the daughter of Time, and not Authority?

What feature of cognition and what are the contradictions of the process of cognition referred to in the following remark: "In order to cognize, a person must separate what should not be separated ...". /. Goethe

3D task

The absolutization of which side of the process of cognition is ironically criticized by the philosopher in the following question: "If the moth corroded and ate the whole fur coat, does this mean that it understood and studied this coat?" A. Losev.

Most agree that scientific knowledge is the highest form of knowledge. Science has a huge impact on the life of modern man. But what is science? How does it differ from such types of knowledge as ordinary, artistic, religious, and so on? This question has been answered for a long time. Even ancient philosophers were looking for the difference between true knowledge and changeable opinion. We see that this problem is one of the main ones in positivism. It was not possible to find a method that would guarantee the receipt of reliable knowledge or at least distinguish such knowledge from unscientific one. But it is possible to single out some common features that would express the specifics of scientific knowledge.

The specificity of science is not its accuracy, since accuracy is used in technology, in public administration. The use of abstract concepts is not specific either, since science itself also uses visual images.

The specificity of scientific knowledge is that science exists as a system of theoretical knowledge. Theory is a generalized knowledge that is obtained using the following methods:

1. Universalization- extension of the general moments observed in the experiment to all possible cases, including those not observed. ( « All bodies expand when heated.

2. Idealization- in the formulations of laws, ideal conditions are indicated, which in reality do not exist.

3. Conceptualization- in the formulation of laws, concepts borrowed from from other theories having exact meaning and meaning.

Using these techniques, scientists formulate the laws of science, which are generalizations of experience that reveal recurring, necessary essential connections between phenomena.

Initially, based on the classification of empirical data ( empirical level of knowledge) generalizations are formulated in the form of hypotheses (beginning theoretical level knowledge). A hypothesis is a more or less substantiated but unproven assumption. Theory- it's a proven hypothesis, it's a law.

Laws make it possible to explain already known phenomena and predict new phenomena without resorting to observations and experiments for the time being. Laws limit their scope. Thus, the laws of quantum mechanics are applicable only to the microworld.

Scientific knowledge is based on three methodological guidelines (or principles):

· reductionism- the desire to explain the qualitative originality of complex formations by the laws of lower levels;

· evolutionism- assertion of the natural origin of all phenomena;

· rationalism- as opposed to irrationalism, knowledge based not on proof, but on faith, intuition, etc.

These principles make science distinct from religion:

a) supranational, cosmopolitan;

b) she strives to become the only one;

c) scientific knowledge is transpersonal;

d) science is open in nature, its knowledge is constantly changing, supplementing, etc.

In scientific knowledge, empirical and theoretical levels are distinguished. They fix the differences in the way, methods of cognitive activity of scientists and the nature of the extracted material.

The empirical level is the subject-tool activity of scientists, observations, experiment, collection, description and systematization of scientific data and facts. There are both sensory cognition and thinking as characteristics of cognition in general. The theoretical level is not all thinking, but that which reproduces internal, necessary aspects, connections, the essence of the phenomenon under study, hidden from direct perception.

Empirical methods include:

Observation - connected with testing the hypothesis systematically, systematically;

measurement - a special type of observation, in which a quantitative characteristic of an object is given;

· modeling - a type of experiment, when direct experimental research is difficult or impossible.

The theoretical methods of scientific knowledge include:

induction - a method of transition from knowledge of individual facts to knowledge of the general (Types of induction: analogy, model extrapolation, statistical method etc.);

· deduction - a method when other statements (from the general to the particular) are logically deduced from the general provisions (axioms).

Along with other methods, historical and logical methods of cognition operate in science.

The historical method is the study real history object, reproduction of the historical process to reveal its logic.

The logical method is the disclosure of the logic of the development of an object by studying it at the highest stages of the historical process, since at the highest stages the object reproduces its historical development in a compressed form (ontogenesis reproduces phylogeny).

What kind of knowledge does a person have that is not included in science?

Is it a lie, delusion, ignorance, fantasy? But isn't science wrong? Isn't there some truth in fantasy, in deceit?

Science has an area of intersection with these phenomena.

a) Science and fantasy. Jules Verne - out of 108 ideas, 64 have come true or will soon come true, 32 are feasible in principle, 10 are recognized as erroneous. (HG Wells - out of 86 - 57, 20, 9; Alexander Belyaev - out of 50 - 21, 26, 3, respectively.)

b) Science and culture. At the present time, criticism of science has been deployed. The historian Gilanski says this about the scientists: “If it were their will, they would turn magnificent flowering into botany, into meteorology the beauty of sunsets.”

Ilya Prigogine also argues that science reduces the wealth of the world to monotonous repetition, removes reverence for nature and leads to domination over it. Feyerabend: “Science is the theology of scientists, emphasizing the general, science coarsens things, opposes itself to common sense, morality. Life itself is to blame for this, with impersonal relationships through writing, politics, money. Science must be subordinated to morality.Criticism of science should be considered fair only from the standpoint of a person who has refused to use its results. Humanism implies the right of every person to choose the meaning and way of life. But the one who enjoys its fruits has no moral right to criticism. The development of culture is already unthinkable without the development of science. To eliminate the consequences of the development of science, society uses science itself. The rejection of science is the degradation of modern man, a return to the animal state, to which a person is unlikely to agree.

So knowledge is a complex process. The highest form of cognition is scientific cognition, which has a complex structure, its own specificity, which elevates science, makes its knowledge generally accepted, but at the same time separates science from the individual, from morality, and common sense. But science does not have impenetrable boundaries with non-science, and should not have them in order not to cease to be human.

Review questions:

1. How did the materialists of antiquity show the difference between the phenomena of consciousness and material things?

2. What is the qualitative difference between the phenomena of consciousness and material things?

3. How to define the ideal, how does it differ from the material?

4. How is consciousness related to matter? What are the possible answers?

5. What is a psychophysiological problem?

6. What is a psychophysical problem?

7. Dialectical materialism believes that all matter has a property that has a different development at different levels of matter, and at the highest level becomes human consciousness. What is this property?

8. What problem in dialectical materialism should the theory of reflection in dialectical materialism solve?

9. What problem in the explanation of consciousness arises in dialectical materialism with the acceptance of the theory of reflection?

10. Why did consciousness arise only in humans? Could it not have happened?

11. Is it possible to say that thinking and speech are one and the same, that there is no thought without words? Do animals have a mind?

12. What is the subconscious?

13. What is the unconscious in the human psyche?

14. What is "superconsciousness" in the human psyche?

15. What is parapsychology?

16. What is telepathy?

17. What is telekinesis?

18. What is clairvoyance?

19. What is psychic medicine?

20. What is knowledge?

21. What problem in cognition did the Eleatics (Parmenides and Zeno) discover and what solution did they propose?

22. What question do agnostics answer in the negative?

23. We have two sources of knowledge. One source is the mind, the other - feelings, sensations. What is the source of reliable knowledge?

24. From what idea of R. Descartes did the materialistic sensationalism of D. Locke and the subjective-idealistic sensationalism of D. Berkeley follow?

26. G. Helmholtz believed that our sensations are symbols of things (not at all similar), G.V. Plekhanov compared sensations with hieroglyphs (slightly similar), V.I. Lenin called them copies of photographs of things (very similar). Who was closer to the truth?

27. “One hand is cold, the other is hot, we lower them into normal water. One hand feels warm, the other cold. What is water, really? - asks D. Berkeley.

What is the philosophical problem they posed?

28. What options are generally possible for understanding the truth, if we are talking about the correspondence of knowledge and what this knowledge is about?

29. How did the ancient materialists understand the truth?

30. How should the understanding of truth differ between metaphysicians and dialecticians?

31. What did objective idealists understand by truth? Which side of the truth did they emphasize?

32. What does dialectical materialism consider to be true? Which side of the truth is he pointing to?

33. What is the criterion of truth for pragmatists? Which side of the truth is he exaggerating?

34. What side of our knowledge does irrationalism point to?

35. What is the criterion of truth in subjective idealism? Which side of the truth is exaggerated?

36. What is considered truth in conventionalism? Which side of the truth is being emphasized?

37. What definition of truth can be considered correct?

39. Is the use of abstract concepts specific to science?

40. In what form does scientific knowledge exist?

41. What is a scientific theory?

42. Soviet psychologist P.P. Blonsky explained the origin of a human smile from the grin of animals at the sight of food. What scientific principle did he follow?

43. What is the difference between scientific knowledge and religious and artistic?

44. In scientific knowledge, empirical and theoretical levels are distinguished. They fix the differences in the way, methods of cognitive activity of scientists and the nature of the extracted material.

What level does it belong to?

- classification of facts (for example, classification of plants, animals, mineral samples, etc.);

- creation of a mathematical model of the phenomenon under study?

45. The theoretical methods of scientific knowledge include induction and deduction. What is their difference?

46. Is there anything scientific in lies, delusions, fantasies?

In general, we can talk about the plurality of forms of knowledge: scientific, artistic, religious, everyday, mystical, etc. Science differs from other areas of human spiritual activity in that the cognitive component in it is dominant. distinguish the following features of scientific knowledge:

- rationality of scientific cognitive activity. Traditionally, rationality is understood as a predominant appeal to the arguments of reason and reason and the maximum exclusion of emotions, passions, personal opinions - when making decisions. Rationality is usually associated with following certain rules. Although classical rationality is usually opposed to empiricism and sensationalism, scientific rationality includes sensory experience and experiment. However, they, in turn, are subject to the arguments and laws of scientific logic.

- allocation of theoretical and empirical components of scientific knowledge

- conceptual activity

- evidence

- consistency

This allows science to perform basic cognitive functions:

- description

- explanation

- prediction of phenomena (based on identified patterns)

There are the following stages in the development of ideas about scientific rationality:

- classical S → O (until the middle of the 19th century)

- non-classical S ↔ O (until the middle of the 20th century)

- post-non-classical S →↔ O (today)

Classical rationality is associated with the deductive model (Euclid, Aristotle, Descartes) and the inductive model (F. Bacon). Its possibilities have exhausted themselves by the middle of the nineteenth century.

The emergence of non-classical ideas about rationality was facilitated by both the development of irrational philosophy (in the second half of the 19th century) and the development of positivism.

The post-non-classical stage is connected with the fact that the problems of scientific knowledge have acquired a new perspective in the new paradigm of rationality, in connection with the development of scientific and technological civilization and the identification of the inhumane consequences of such development. This gave rise to active opposition to the cult of scientific rationality and manifested itself in a number of approaches of the schools of modern irrationalism. In irrationalism, the main principles of the epistemology of rationalism are criticized for their abstract, inherently inhuman nature. In rationalism, the subject of knowledge is alien to the consciousness of the researcher. the mental activity of the subject is perceived only as a method for obtaining a specific result. Moreover, the cognizing subject does not care what application this result will find. The search for objective truth in rationalism has a tinge of anti-subjectivity, anti-humanity, a soulless attitude to reality. On the contrary, representatives of irrationalism oppose the rupture of cognitive action into subject-object relations. For example, in the personalistic concept of cognition (N. A. Berdyaev), cognition is seen as involvement, as an all-encompassing movement that unites the subject with the entire surrounding world. The theory of knowledge includes the emotional-sensory and emotional-volitional factors of love and faith as the main cognitive means. Personalists emphasize personal, value, emotional and psychological moments of knowledge, the presence in it of moments of volitional choice, satisfaction, etc.

Since positivism has a special role in the development of the methodology of scientific knowledge, we will consider this philosophical trend in more detail. Positivism arises in the 30s and 40s. 19th century France. Ancestor - O. Comte. Positivism (from Latin positivus - positive) is considered by him as the highest stage in the development of thinking, moving along the path from the mythological to the metaphysical and reaching the highest level - in positivism. Positivism calls for abandoning metaphysical abstractions and turning to the study of positive, real knowledge, precise and concrete. Positivism proceeds from the recognition of a given, that is, positive reality, that which can be verified by empirical or logical-mathematical means. This verification (verification) should be of a generally significant nature. Positivism seriously claimed to be the "philosophy of science". The positivist systems of Comte, Spencer, Mill created a certain scientific picture of the world based on the principle of a mechanical interpretation of reality.

But the development of quantum physics at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries. called into question the mechanistic methodology based on the principles of Newtonian physics and destroyed the old picture of the world. The empirical methodology of scientific knowledge was also called into question, since the research revealed the dependence of the results of scientific experiments on instruments and human senses. The intensive development of psychological research has put on the agenda the question of the relationship of this science with other sciences that study a person and the world around him. A new picture of the world began to take shape. When, for example, R. Feynman developed ideas about the interactions of charges without "field mediators", he was not embarrassed by the fact that it was necessary to introduce into the theory being created, along with retarded potentials, which in the physical picture of the world corresponded to the emergence of ideas about the influence of interactions of the present not only for the future, but also for the past. “By this time,” R. Feynman wrote, “I was already sufficiently a physicist not to say:“ Well, no, this cannot be. After all, today, after Einstein and Bohr, all physicists know that sometimes an idea that seems completely paradoxical at first glance can turn out to be correct after we understand it to the smallest detail and to the very end and find its connection with experiment. But "to be a physicist" of the XX century. - something other than "being a physicist" in the 19th century.

As a result of the ongoing changes, positivism is experiencing a serious crisis, which coincides with the crisis of classical rationality in general, thus contributing to the transition to non-classical and post-non-classical ideas about rationality.

There is a second stage in the development of positivism - empirio-criticism (criticism of experience) E. Mach, R. Avenarius, which soon outgrows

in the third stage, in a serious course - neopositivism associated with the logical analysis of language (B. Russell, L. Wittgenstein). Here again the principle of verification (testing for truth) is applied, but now in relation to scientific statements and generalizations, that is, to linguistic expressions. This stage made a great contribution to the philosophical study of language.

The fourth stage of positivism, neo-positivism - "critical rationalism" is associated with the names of K. Popper, T. Kuhn, I. Lakatos, P. Feyerabend. It is characterized by the fact that the subject of study is science as an integral developing system. The authors proposed various models for the development of science, the main ones we will consider in the next question.

2. Scientific revolutions and changing types of rationality

Considering the patterns of development of science as an integral system, the founder of critical rationalism K. Popper came to the conclusion that the laws of science are not expressed by analytical judgments and are not reducible to observations, that is, they are not verifiable. Therefore, science does not need the principle of verification (since there is always a temptation to take into account the facts that confirm the theory, and not to take into account the facts that refute it), but the principle of falsification, that is, not a confirmation of the truth, but a refutation of the truth.

The principle of falsification is not a method of empirical verification, but a certain attitude of science to a critical analysis of the content of scientific knowledge, to the constant need for a critical review of all its achievements. Popper argues that science is a constantly changing system in which the process of theory restructuring is constantly taking place, and this process needs to be accelerated.

Further, this idea was developed by T. Kuhn, who emphasized that the development of science is carried out by a community of professional scientists acting according to unwritten rules that regulate their relationship.

The main unifying principle of the community of scientists is a single style of thinking, the recognition by this community of certain fundamental theories and research methods. These provisions that unite communities of scientists, Kuhn called the paradigm. “By paradigm, I mean scientific advances that are universally recognized and that, over time, provide the scientific community with a model for posing problems and solving them.” Each scientific theory is created within the framework of a particular scientific paradigm.

Kuhn presents the development of science as a spasmodic revolutionary process, the essence of which is expressed in a change of paradigms.

The period of "normal science" with a certain paradigm is replaced by a period of scientific revolution, during which a new scientific paradigm is established and science is again in the state of "normal science" for some time. The transition from the old paradigm to the new one cannot be based on purely rational arguments, although this element is significant. It also requires volitional factors - conviction and faith. It is necessary to believe that the new paradigm will succeed in solving a wider range of problems than the old one.

The most radical position in critical rationalism is taken by the American philosopher P. Feyerabend. Based on the assumption that the old theory is sooner or later refuted by the new one, he put forward the methodological principle of the proliferation (reproduction) of theories, which, in his opinion, should contribute to criticism and accelerate the development of science: new theories should not be compared with the old ones, and each of them should establish their own norms. He also affirms the principle of methodological anarchism, according to which the development of science is irrational and that theory wins, the propaganda activity of whose supporters is higher.

1. Integrative(synthetic) function of philosophy is a systemic, holistic generalization and synthesis (unification) of various forms of knowledge, practice, culture - the entire experience of mankind as a whole. Philosophical generalization is not a simple mechanical, eclectic unification of particular manifestations of this experience, but a qualitatively new, general and universal knowledge. For philosophy, as for all modern science, it is precisely synthetic, integrative processes that are characteristic - intradisciplinary, interdisciplinary, between natural science and the social sciences and humanities, between philosophy and science, between forms of social consciousness, etc. 2. critical the function of philosophy, which in this function is focused on all spheres of human activity - not only on knowledge, but also on practice, on society, on the social relations of people. Criticism- a method of spiritual activity, the main task of which is to give a holistic assessment of the phenomenon, to identify its contradictions, strong and weak sides. There are two main forms of criticism: a) negative, destructive, "total negation", rejecting everything and everything; b) constructive, creative, not destroying everything “to the ground”, but preserving everything positive of the old in the new, offering specific ways to solve problems, real methods of resolving contradictions, effective ways overcoming delusions. In philosophy, both forms of criticism are found, but the most productive is constructive criticism. Criticizing ideas existing world, the philosopher criticizes voluntarily or involuntarily - this world itself. The absence of a critical approach inevitably turns into apologetics - a biased defense, praising something instead of an objective analysis. 3. Philosophy develops certain "models" of reality, through the "prism" of which the scientist looks at his subject of study ( ontological function). Philosophy gives the most general picture of the world in its universal objective characteristics, represents material reality in the unity of all its attributes, forms of movement and fundamental laws. This holistic system of ideas about the general properties and patterns of the real world is formed as a result of generalization and synthesis of the main private and general scientific concepts and principles. Philosophy gives a general vision of the world not only in the form it was before (past) and what it is now (present). Philosophy, carrying out its cognitive work, always offers humanity some possible options his life world. And in this sense, it has predictive functions. Thus, the most important purpose of philosophy in culture is to understand not only what the present human world is like in its deep structures and foundations, but what it can and should be. 4. Philosophy “arms” the researcher with knowledge of the general laws of the cognitive process itself, the doctrine of truth, ways and forms of its comprehension ( epistemological function). Philosophy (especially in its rationalistic version) provides the scientist with initial epistemological guidelines about the essence of the cognitive relationship, about its forms, levels, initial premises and general grounds, about the conditions for its reliability and truth, about the socio-historical context of cognition, etc. Although everything private sciences carry out the process of cognition of the world, none of them has as its direct subject the study of the laws, forms and principles of cognition in general. Philosophy (more precisely, epistemology, as one of its main sections) is specially engaged in this, relying on data from other sciences that analyze certain aspects of the cognitive process (psychology, sociology, science of science, etc.). In addition, any knowledge of the world, including scientific, in each historical era is carried out in accordance with a certain "network of logical categories". The transition of science to the analysis of new objects leads to a transition to a new categorical grid. If a culture has not developed a categorical system corresponding to a new type of objects, then the latter will be reproduced through an inadequate system of categories, which does not allow revealing their essential characteristics. By developing its categories, philosophy thus prepares for natural science and the social sciences a kind of preliminary program for their future conceptual apparatus. The application of the categories developed in philosophy in a concrete scientific search leads to a new enrichment of the categories and the development of their content. However, as the modern American philosopher notes R. Rorty, "we must free ourselves from the notion that philosophy (with its entire "network of categories" - V. K.) can explain what science leaves unexplained "*. 5. Philosophy provides science with the most general methodological principles formulated on the basis of certain categories. These principles actually function in science in the form of universal regulators, universal norms, requirements that the subject of knowledge must implement in his research ( methodological function). By studying the most general patterns of being and cognition, philosophy acts as the ultimate, most general method of scientific research. This method, however, cannot replace the special methods of the particular sciences, it is not a universal key that reveals all the secrets of the universe, it does not a priori determine either the specific results of the particular sciences or their peculiar methods. The philosophical and methodological program should not be a rigid scheme, a “template”, a stereotype according to which “facts are cut and reshaped”, but only a “general guide” for research. Philosophical principles are not a mechanical "set of norms", "a list of rules" and a simple external "overlay" of a grid of universal categorical definitions and principles on a specially scientific material. Aggregate philosophical principles- a flexible, mobile, dynamic and open system, it cannot "reliably provide" pre-measured, fully guaranteed and obviously "doomed to success" moves of research thought. Nowadays, an increasing number of specialists are beginning to realize that in the conditions of the information explosion that our civilization is experiencing, considerable attention should be paid to methods of orientation in the vast factual material of science, methods of its research and application. 6. From philosophy, a scientist receives certain worldview, value orientations and life-sense orientations, which - sometimes to a large extent (especially in the humanities) - influence the process of scientific research and its final results ( axiological function).Philosophical thought reveals not only intellectual (rational), but also moral-emotional, aesthetic and other human universals, always related to specific historical types of cultures, and at the same time belonging to humanity as a whole (universal values). 7. To the greatest extent, philosophy influences scientific knowledge in the construction of theories (especially fundamental ones). This selective (qualifying) function most actively manifested during periods of "abrupt break" of concepts and principles in the course of scientific revolutions. Obviously, this influence can be both positive and negative - depending on what philosophy - "good" or "bad" - the scientist is guided by, and which philosophical principles he uses. In this regard, W. Heisenberg's statement that "bad philosophy gradually destroys good physics" is well known. BUT. Einstein rightly believed that if philosophy is understood as the search for knowledge in its fullest and broadest form, then philosophy is undoubtedly “the mother of all scientific knowledge”. More specifically, the influence of philosophy on the process of special scientific research and the construction of theory lies, in particular, in the fact that its principles, in the transition from speculative to fundamental theoretical research, perform a kind of selective function. The latter consists in in particular, in the fact that out of many speculative combinations, the researcher implements only those that are consistent with his worldview. But not only with him, but also with the philosophical and methodological orientations of the scientist. The history of science provides many examples of this. Philosophical principles as selectors “work”, of course, only when the very problem of choice arises and there is plenty to choose from (certain speculative constructs, hypotheses, theories, various approaches to solving problems, etc.). If there are many options for solving a specific scientific problem and it becomes necessary to choose one of them, then experimental data, previous and coexisting theoretical principles, “philosophical considerations”, etc. * 8. Philosophy has a significant impact on the development of knowledge speculatively -predictive function. It's about Such, in particular, are the ideas of ancient atomism, which became a natural scientific fact only in the 17th-18th centuries. Such is developed in philosophy Leibniz categorical apparatus expressing some general features of self-regulating systems. This is also the Hegelian apparatus of dialectics, which "anticipated" the essential characteristics of complex self-developing systems - including the ideas of synergetics, not to mention quantum mechanics (complementarity, activity of the subject, etc.). Pointing to this circumstance, M. Born emphasized that "much of what physics thinks about, was foreseen by philosophy." That is why it is a very useful thing to study philosophy (in its most varied forms and directions) by representatives of the particular sciences, which was done by the great creators of science. 9. Philosophical and methodological principles - in their unity - perform in a number of cases function auxiliary, derivative The impact of philosophical principles on the process of scientific research is always carried out not directly and directly, but in a complex indirect way - through the methods, forms and concepts of "underlying" methodological levels. The philosophical method is not a "universal master key", it is not possible to directly obtain answers to certain problems of particular sciences from it through a simple logical development of general truths. It cannot be an "algorithm of discovery", but gives the scientist only the most general orientation of research, helps to choose the shortest path to the truth, to avoid erroneous trains of thought. Philosophical Methods do not always make themselves felt in the process of research in an explicit form, they can be taken into account and applied either spontaneously or consciously. But in any science there are elements of universal significance (for example, laws, categories, concepts, principles, etc.), which make any science "applied logic". Philosophy rules in each of them, because the universal (essence, law) is everywhere (although it always manifests itself specifically). The best results are achieved when the philosophy is "good" and applied in scientific research quite consciously. It should be said that the wide development in modern science intrascientific methodological reflections does not "abolish" philosophical methods, does not eliminate them from science. These methods are always present in the latter to some extent, no matter how mature its own methodological means may be. Philosophical methods, principles, categories "penetrate" science at each stage of its development. The implementation of philosophical principles in scientific knowledge means at the same time their rethinking, deepening, development. Thus, the way of realizing the methodological function of philosophy is not only a way of solving fundamental problems science, but also a way of developing philosophy itself, all its methodological principles. |

ON THE VALUE OF PHILOSOPHY

According to Kant, the dignity of philosophy is determined by the "world concept" of it, as the science of the ultimate goals of the human mind. In the context of the above, it is the knowledge of the ultimate goals of our mind by the human mind itself that determines the "absolute value" of philosophy. Consequently, it is philosophy as a science that has an absolute intrinsic value that can act as a kind of “qualification” for other types of knowledge. The latter, in turn, will dictate, and in systemic philosophy it dictated in one way or another, the three-dimensional organization of philosophy as a “censoring” science: knowledge, their systematic unity, the expediency of this unity in relation to ultimate goals. The specified organization of the structure of philosophy will also give rise to its own, purely internal problems, which in general terms can be defined as a discrepancy between knowledge taken systematically and the final goals.

It should be noted that goals, depending on the level of development of the mind, its culture, can act as "higher" and "ultimate" and only in a narrowly objective sense. In this case, we will talk about the goals that form the philosophy of everyday consciousness, and, accordingly, the ordinary logic of actions. The internal value of these goals and the philosophy that expresses them can be characterized as a single-subjective value, which can acquire the features of an “absolute” value only for a concrete, professing consciousness.

Higher subjective goals may appear as another kind of subjective goals. Accordingly, here we will talk about the ultimate and higher goals of personality and individuality, setting the problematic field of ethics and aesthetics. The highest subjective goals, in principle, should be thought of as goals associated with the ultimate goals of world philosophy, since the latter, according to Kant's views, is also a practical science, a science of the principles of the application of reason, or the "highest maxim" of the latter's application.

The search for a systematic unity for renewing knowledge and the search for conformity to higher purposes can be seen as the dynamic components of philosophy. Knowledge of ultimate goals - as its internal constant. Hence, ignorance of higher goals is a situation that deprives world philosophy of its "absolute" foundation and world dignity. In addition, in this situation, the organization of the internal structure of philosophy as values and a systematizing discipline breaks down.

What does it mean that the mind does not strive to know its ultimate goals?

Knowledge of higher and final goals by the human mind, according to Kant, is its freedom. Consequently, the absence of the desire of our mind to know its ultimate goals is nothing but the death of the freedom of reason, and as a consequence, the death of philosophy as such.

But Kant speaks not only of the freedom of reason, but also of its free use. The free application of reason is its application not as an analogue of instinct in the sphere of natural certainty, but its application in the field of freedom as an autonomous principle. Consequently, the free use of reason is also the determination by the latter of the will to "action" for the creation of the "object" of the ultimate goal. Thus, the knowledge of final goals should be understood not only as a free determination, but always also as a determination of the will to create them. And thus, we must speak both of the highest qualitative definiteness of thinking, and of the highest "qualitative" definiteness of will.

Thus, the knowledge of final ends turns out to be, in principle, a positing in the supersensible. Accordingly, the philosophy that defines these goals must necessarily be thought of as metaphysics. But metaphysics, in its definition by Kant in relation to our mind, is the level of the highest culture of the organization of the latter. Consequently, it is metaphysics that will correspond to the status of the highest qualitative certainty of thinking. In addition, since within the framework of the above provisions we think at the same time a volitional orientation, then metaphysics itself appears as a "discipline" as well as a practical one. Moreover, based on the initial data, metaphysics as a purely theoretical discipline is not possible at all.

If in terms of the reflexive subject of determining the final goals is the "I" of the philosopher, then in terms of metaphysical consideration, this subject, in theory, should be the personality as an intelligible person and the subject of practical freedom. Hence the very fact of the mind's striving for knowledge of higher goals is a manifestation of volitional orientation, and the definition of these goals, their vision is an intelligible action.

Further, if we accept that the knowledge of final ends is always also an intelligible action, then metaphysical reasoning will be a reasoning not about "metaphysical" constants or "realities", but about the "becoming" supersensible. Or, metaphysical discourse is a reflection, which is preceded by a certain vision of what is not given, the clarity of contemplation of the “unearthly” increases with the course of reflection. Accordingly, a decrease in the degree of clarity of what is being seen will indicate that the course of reasoning is destructive. Thus, the ultimate goals of the human mind can also be thought of as an eternally determined, but indefinite supersensible, having only the creative mind as its “absolute” reality and sphere of freedom.

From the foregoing, we can conclude that metaphysics will encounter the deepest contradictions, and, as a result, the deepest internal problems, not from the side of knowledge about the phenomenal or physical world, but from the side of “knowledge” about the supersensible world, unless, of course, we admit that these may take place.

Representations that claim to be characterized as knowledge about the supersensible, world philosophy meets in the face of religious experience and esoteric practices. Both those and other representations provide information about the specifics of the supersensible, one way or another defined. But the specificity of the supersensible, taken in terms of philosophical consideration, is the area of immanent metaphysics, with all the "incomprehensibility", and in the language of philosophy - the false transcendence of its content. In this situation, the metaphysics of final goals must not only comprehend the "givens" of the supersensible, but also link a certain organization of "other worlds" with the possibility of higher goals of reason. However, both religious philosophy and esoteric views touch on the same controversy on their part, and, one way or another, also claim to know the ultimate goals. Consequently, both of these "disciplines" will challenge philosophy's claims to both world dignity and, accordingly, its "absolute" intrinsic value.

Disadvantages: This concept cannot answer the question of how consciousness arises. Positivism denies almost all the previous development of philosophy and insists on the identity of philosophy and science, and this is not productive, since philosophy is an independent field of knowledge based on the entire array of culture, including science.

Philosophy of Auguste Comte (1798-1857) (the founder of positivism, introduced this concept in the 30s of the XIX century), Mill, Spencer - 1 historical form of positivism. According to Comte: in science, the description of phenomena should come first. The methods of the natural sciences are applicable to the analysis of society, sociology is a basic science in which positivism can show all its possibilities, contributing to the improvement of the language of science and the progress of society, a look at the general mental development of mankind, the result of which is positivism, indicates that there is a basic law . According to this law, three stages of human development are distinguished:

1. theological (state of fiction) - the necessary point of departure of the human mind.

2. metaphysical (abstract). An attempt to build a general picture of being, the transition from the first to the third.

3. positive (scientific, positive). - solid and final state.

Disadvantages: not a critical approach to science, its praise, hasty conclusions are typical.

The second form of positivism combines Machism (Mach) and empirio-criticism (Avenarius) under the general name "the latest philosophy of natural science of the 20th century." The main attention of the Machists was given to explaining the "physical" and "mental" elements of the world in the experience of people, as well as "improving the" positive "language of science. Avenarius tried to build a new philosophy as a rigorous and exact science, similar to physics, chemistry and other specific sciences, substantiating philosophy as a method of saving thinking, the least waste of energy. Mach paid more attention to the liberation of the natural sciences from metaphysical, speculative-logical philosophy.

Neoposite of the concept of f n. The teachings on phn by the outstanding thinkers of the 20th century L. Wittgenstein and K. Popper belong to the 3rd stage of philo-positivism, which is called “linguistic positivism” or “neo-positivism”. The main ideas of the thinker in the field of ph are as follows: n needs to purify his language. L. Wittgenstein put forward the principle of "verification", according to which any statement in n is verifiable, i.e. subject to experimental verification.

K. Popper, in the course of studying the essence of n, its laws and methods, came to ideas that are incompatible with the principle of verification. In his works Logic and Discoveries (1959), Assumptions and Refutations (1937) and others, he puts forward the idea that it is impossible to reduce the content of n, its laws only to statements based on experience, i.e. to observation, experiment, etc. H cannot be reduced to verifiable propositions. H knowledge, the thinker believed, acts as a set of guesses about the laws of the world, its structure, and so on. At the same time, the truth of conjectures is very difficult to establish, and false conjectures are easily proved. PR, the fact that the Earth is flat and the Sun walks above the Earth is easy to understand, but the fact that the Earth is round and revolves around the Sun was difficult to establish, in the struggle with the church and with a number of scientists.

Post-positivist fiction of the 20th century is represented by the works of T. Kuhn, I. Lakatos, P. Feyerabend, M. Polanyi. general installation on the analysis of the role of socio-cultural factors in the dynamics of n. T. Kuhn managed to overcome some of the shortcomings inherent in the positivist views on n. In n there is no continuous progress and cumulation of knowledge. Each paradigm forms a unique understanding of the world and has no special advantages over the other paradigm. Progress is better understood as evolution - the growth of knowledge within the paradigm. H is always socioculturally conditioned. To understand n, a new historical-evolutionary approach is needed. Truths are rather relative, they operate within the framework of a paradigm. These ideas have influenced modern philosophy of science.

Modern fn speaks on behalf of natural science and humanitarian knowledge, trying to understand the place of modern civilization in its diverse relationship to ethics, politics, religion. Thus, f n also performs a general cultural function, preventing scientists from becoming ignorant, absolutizing a narrowly professional approach to phenomena and processes. It calls to pay attention to the phil plan of any problem, to the relation of thought to reality in its entirety and multidimensionality, appears as a detailed diagram of views on the problem of growth and knowledge.

3. Science (from Lat - knowledge) as a part of culture. The relationship of science with art, religion and philosophy. Science in the modern world can be considered in various aspects: as knowledge and activities for the production of knowledge, as a system of personnel training, as a direct productive force, AS A PART OF SPIRITUAL CULTURE.

Philosophy. Philosophical problems of scientific knowledge

Notes |

Questions and answers on philosophy, namely the courses "Philosophical problems of scientific knowledge".

What is science?

The science is an activity aimed at obtaining true knowledge.

What does science include?

Science includes:

1. Scientists in their knowledge, qualifications and experience.

2. Scientific organizations and institutions, scientific schools and communities.

3. Experimental and technical base of scientific activity.

4. Well-established and efficient system of scientific information.

5. The system of training and certification of personnel.

The functions of science.

Science performs the following functions:

1. Determines social processes.

2. Is the productive force of society.

3. Performs an ideological function.

What are the types of knowledge?

1. Ordinary

2. Scientific

3. mythological

4. religious

5. philosophical

6. artistic

Most characteristics ordinary knowledge

1. It develops spontaneously under the influence of daily experience.

2. Does not involve setting tasks that would go beyond everyday practice.

3. Due to the social, professional, national, age characteristics of the carrier.

4. The transfer of knowledge involves personal communication with the carrier of this knowledge

5. Consciously not in in full

6. Low level of formalization.

What is mythological knowledge?

mythological knowledge- this is a special kind of holistic knowledge within which a person seeks to create a holistic picture of the world based on a set of empirical information, beliefs, various forms of imaginative exploration of the world.

Mythological knowledge has an ideological character.

The source of myths is incomplete knowledge.

What is religious knowledge?

religious knowledge- this holistic worldview knowledge is due to the emotional form of people's attitude to the higher forces (natural and social) dominating them.

Religious knowledge is based on belief in the supernatural. Religious knowledge is dogmatic.

What is artistic knowledge?

artistic knowledge- this is knowledge based on artistic experience - this is visual knowledge.

Features of scientific knowledge

1. Strict evidence, validity, reliability of results

2. Orientation to objective truth, penetration into the essence of things

3. Universal transpersonal character

4. Reproducibility of the result

5. Logically organized and systematic

6. Has a special, highly formalized language

Structure of scientific knowledge

In the structure of scientific knowledge, depending on the subject and method of research, there are:

1. Natural science or the science of nature

2. Social science or social and humanitarian knowledge

3. Engineering sciences

4. Mathematics

5. Philosophy

By distance from practice, science can be divided into:

1. Fundamental

2. Applied

Levels of Scientific Research

1. metatheoretical

2. Theoretical

3. Empirical

Features of the empirical level of knowledge

1. Subject of study: external aspects of the object of study

2. Research methods: observation, experiment

3. Epistemological orientation of the study: the study of phenomena

4. The nature and type of knowledge gained: scientific facts

5. Cognitive functions: descriptions of phenomena

What is observation?

Observation- this is a systematic, purposeful, systematic perception of objects and phenomena of the external world.

Observation can be:

1. Direct

2. Indirect (using various devices)

Observation Method Limitations:

1. Narrowness of the range of perception of various senses

2. Passivity of the subject of knowledge, i.e. fixing what happens in a real process without interfering with it.

What is an experiment?

Experiment is a research method by which phenomena are studied under controlled and controlled conditions.

A scientific experiment involves:

1. Existence of research purpose

2. Based on certain initial theoretical assumptions

3. Requires a certain level of development of technical means of knowledge

4. Carried out by people who have a fairly high qualification

Benefits of the experiment:

1. It is possible to isolate the object from the influence of side objects that obscure its essence

2. Systematically change the conditions of the process

3. Repeat playback

Types of experiment:

1. Search engine

2. Checking

3. Demonstrative

Experiment types:

1. Natural

2. Mathematical

3. Computing

What is a scientific fact?

scientific fact- it is always reliable, objective information - a fact expressed scientific language and included in the system of scientific knowledge.

Features of the theoretical level of scientific knowledge

1. Subject of study: idealized objects formed as a result of idealization.

2. Epistemological orientation: knowledge of the essence, causes

3. Methods: simulation

4. Cognitive functions: explanation, prediction

5. The nature and type of knowledge obtained: hypothesis, theory

The main forms of knowledge at the theoretical level of knowledge

1. Hypothesis

2. Theory

What is a hypothesis?

Hypothesis- an unproven logical assumption based on facts.

Hypothesis is a scientifically based assumption based on facts.

Hypothesis- probabilistic knowledge, a conjectural solution to a problem.

Ways to form a hypothesis:

1. Based on sensory experience

2. Using the method of mathematical hypotheses

Basic requirements for a hypothesis

1. A hypothesis must be compatible with all the facts it concerns

2. Should be accessible to empirical verification or logical proof

3. Must explain facts and have the ability to predict new facts

What is a theory?

Theory- this is a system of reliable knowledge, objective knowledge, proven, practice-tested knowledge, essential characteristics of a certain fragment of reality.

Theory is a complex system of knowledge, which includes:

1. Initial empirical basis - a set of recorded facts in a given area.

2. The initial theoretical base - a set of assumptions, axioms, laws that describe an idealized object.

3. Rules of inference and proof, admissible within the framework of the theory

4. Laws of varying degrees of generality, which express essential, stable, recurring, necessary connections between phenomena covered by this theory

The relationship between theoretical and empirical levels research

1. Empirical knowledge is always theoretically loaded

2. Theoretical knowledge is empirically verified

Metatheoretical level of scientific knowledge

Metatheoretical knowledge is a condition and a prerequisite for determining the type of theoretical activity to explain and systematize empirical material.

Metatheoretical knowledge- this is a set of norms of scientific thinking for a given era, ideals and norms of scientific knowledge, acceptable ways of obtaining reliable knowledge.

The structure of the metatheoretical level of knowledge

1. Ideals and norms of research

2. Scientific picture of the world

3. Philosophical foundations

The ideals and norms of research are a set of certain conceptual value methodological guidelines inherent in science at each specific historical stage of its development.

Research ideals and norms include:

1. Ideals and norms of evidence and substantiation of knowledge.

2. Description explanation knowledge

3. Building knowledge

The ideals and norms of research are due to:

1. The specifics of the objects under study

2. The image of cognitive activity - the idea of mandatory procedures that ensure the comprehension of truth.

3. Worldview structures that underlie the foundation of the culture of a particular historical era.

What is the scientific picture of the world (SCM)?

Scientific picture of the world is an integral system of ideas about the general properties and patterns of reality.

The scientific picture of the world is built as a result of generalization of fundamental scientific concepts.

The scientific picture of the world ensures the systematization of knowledge within the framework of the relevant science, sets the system of attitudes and priorities for the theoretical development of the world as a whole, and changes under the direct influence of new theories and facts.

Types of scientific picture of the world:

1. classical

2. Non-classical

3. post-non-classical

Most salient features philosophical knowledge

1. Purely theoretical.

2. Has a complex structure (includes ontology, epistemology, logic, and so on).

3. The subject of study of philosophy is wider than the subject of study of any science, it seeks to discover the laws of the entire world whole.

4. Philosophical knowledge is limited by human cognitive abilities. Those. has unresolvable problems that today cannot be resolved in a logical way.

5. He studies not only the subject of knowledge, but also the mechanism of knowledge itself.

6. Bears the imprint of the personality and worldview of individual philosophers.

What is the difference between philosophical knowledge and scientific knowledge?

There are two major differences between them:

1. Any science deals with a fixed subject area (physics discovers the laws of physical reality; chemistry - chemical, psychology - psychological).

Philosophy, unlike science, makes universal judgments and seeks to discover the laws of the entire world.

2. Science searches for truth without discussing whether what it has found is good or bad, and whether there is any sense in all this. In other words, science primarily answers the questions “why?” "how?" and “from where?”, does not ask questions “why?” and for what?".

Philosophy, solving the eternal problems of being, is focused not only on the search for truth, but also on the knowledge and affirmation of values.

Philosophical foundations of science

Philosophical foundations of science is a system of philosophical ideas that set general guidelines for cognitive activity.

Philosophical foundations of science provide "docking" of new scientific knowledge with the dominant worldview, including its socio-cultural context of the era.

What is the name of the historically first form of the relationship between science and philosophy?

Natural philosophy.

What is natural philosophy?

Natural philosophy- this is a way of understanding the world, based on certain speculatively established general principles and giving a general picture that covers all of nature as a whole.

Natural philosophy is a form of interconnection between science and philosophy (culture Western Europe before the beginning of the 19th century)

Natural philosophy- an attempt to explain nature, based on the results obtained by scientific methods, in order to find answers to some philosophical questions.

For example, such sciences as cosmogony and cosmology, which in turn are based on physics, mathematics, and astronomy, are trying to answer the philosophical question about the origin of the Universe.

The main reasons for the death of natural philosophy:

1. The formation of science as social institution

2. Formation of the disciplinary organization of sciences

3. Criticism of the speculativeness of philosophical constructions by major naturalists.

What is positivism?

Positivism- this is philosophy which in the 19th century declared concrete empirical sciences the only source of true knowledge and denied the cognitive value of traditional philosophical research.

Positivism seeks to reduce all scientific knowledge to the totality of sensory data and eliminate the unobservable from science.

According to positivism, the task of philosophy is to find a universal method for obtaining reliable knowledge and a universal language of science. All the functions of science are reduced to description, not explanation.

The initial thesis of positivism: metaphysics, as the doctrine of the essence of phenomena, must be discarded. Science should be limited to describing the external appearance of phenomena. Philosophy must fulfill the task of systematizing, ordering and classifying scientific conclusions.

Founders of Positivism: Comte, Spencer, Mill

What is metaphysics?

Metaphysics- This is the doctrine of the first causes, primary essences.

What is Machism?

Machism or empiriocriticism- this is a modified form of positivism (60-70 years of the XIX century).

What is neopositivism?

Neopositivism is a form of positivism modified in the 1920s.

Reasons for changing the form of positivism: