All things arise from the infinite...

Anaximander

The idea of neutral matter

Thales, with his idea of the systematic development of the natural sciences, became for the Greeks a great pioneer in the field of thought. But modern scholars would rather choose his successor, the more poetic and passionate Anaximander, as their hero. He can truly be called the first true philosopher.

Anaximander went beyond the brilliant but simple assertion that all things are made of the same matter, and showed how deeply the means of objective analysis must penetrate into the real world. He made four well-defined major contributions to people's understanding of the world:

1. He realized that neither water nor any other ordinary substance like it can be the basic form of matter. He imagined this basic form - rather vaguely, though - as a more complex boundless something (which he called "apeiron"). His theory has served science for twenty-five centuries.

2. He transferred the concept of law from human society to the physical world, and this was a complete break with previous ideas about the capricious anarchist nature.

3. He was the first to use mechanical models to help understand complex natural phenomena.

4. He concluded in rudimentary form that the earth is changing over time and that higher forms of life could develop from lower ones.

Each of these contributions by Anaximander is a discovery of the first magnitude. We can get an idea of how important they are if we mentally remove from our modern method thinking everything that is connected with the concepts of what is neutral matter, the laws of nature, the computing apparatus of scales and models, and what is evolution. In this case, little would be left of science and even of our common sense.

Anaximander was from Miletus and was born about forty years after Thales (hence, his mature activity should have begun around 540 BC). They wrote about him that he was a student of Thales and replaced his teacher in the Milesian school of philosophy. But both the date and this information are based on later reports, which are not chronologically accurate and transfer the idea of schools organized according to a certain system to the early period of ancient Greek thought, when in reality there were no such formal associations of philosophers and scientists. However, we can be sure that Anaximander was a junior countryman of Thales, realized and highly appreciated the novelty of his ideas and developed them - exactly as has already been said. Anaximander was a philosopher in the sense that, among the things that interested him, he also dealt with philosophical questions; but in that early period philosophy and science were not yet divided into separate areas. It is better for us to consider Anaximander an amateur than to follow the assumptions of later historians, who carried back their idea of a professional philosopher.

To the already mentioned information about his hometown, time of life and acquaintance with Thales, we can add little. Anaximander was a versatile and practical man. The Milesians chose him as the head of the new colony, which indicates his important role in political life. It is believed that he traveled widely, and this may be confirmed by three facts of his biography: he was the first Greek geographer to draw a map; one of his trips - from Ionia to the Peloponnese - is confirmed by evidence that he created a new instrument in the form of sundial, which measured the length of the seasons; the fact that he saw fossilized fish high in the mountains suggests that he probably climbed the mountains of Asia Minor and carefully peered at what he saw around. Adding to this the tradition of Miletus, the birthplace of engineers, and the fact that Anaximander applied technological methods when he designed tools, maps and models, we can also assume that he, like Thales, was at least an expert in engineering, and possibly even professional engineer.

Anaximander's first major contribution to science was his new method analysis and the concept of "matter". He agreed with Thales that everything in the world consists of a single substance, but believed that it could not be any substance familiar to humans like water, rather it was a “limitless something” (apeiron), in which initially contained all the forms and properties of things, but which itself did not have any specific features characteristic of it.

At this point, Anaximander made an interesting move in his reasoning: if everything that exists in reality is matter with certain properties, this matter should be able to be hot in some cases, cold in others, sometimes wet, and sometimes dry. Anaximander believed that all properties of matter are grouped into pairs of opposites. If we identify matter with one property from such a pair, as Thales did when he said “all things are water”, then the conclusion will follow from this: “to be means to be wet. What then happens when things become dry? If the matter of which they are composed is always wet (as Anaximander defined the Thales word guidor), desiccation would destroy the matter in things, they would become immaterial and cease to exist. In the same way, matter cannot be identified with any one quality and thus exclude its opposite. From this it follows that matter is something boundless, neutral and indefinable. From this "reservoir" opposite qualities are singled out: all concrete things arise from the infinite and return to it when they cease to exist.

This is a movement of philosophical thought from the primitive definition of matter as guidor(water) to understanding matter as an infinite substance is a huge step forward. Indeed, until the 20th century, in the science and philosophy of modern times, matter was often described as a "neutral substance", which is very similar to Anaximander's "apeiron". But there is one fundamental difference between the modern idea and its ancient progenitor: Anaximander did not yet know the difference between the image that the imagination creates and the abstract mental construction. The truly abstract concept of matter did not appear until two hundred years after Anaximander, when the atomistic theory was created. Anaximander could well associate the infinite with the image of a gray fog or a dark haze at sunset, or hills of indefinite outlines on the horizon. Nevertheless, this attempt to define matter - the basis of all physical reality - led directly to those later, more perfect schemes that we find when materialism arises as a fully developed philosophical system.

Anaximander's introduction of models into astronomical and geographical research was an equally important turning point in the development of science. Very few people understand how important models are, although we all use them and cannot do without them. Anaximander tried to design objects by reproducing their inherent linear relationships, but on a smaller scale. One result of this was a pair of maps: a map of the earth and a map of the stars. The map shows the distances to various places and the direction in which you need to move to them. If people had to find out where other cities and countries are from the diaries of travelers and their own impressions, then travel, trade and geographical research would be very difficult activities. Anaximander also built a model that reproduced the movements of the stars and planets; it consisted of wheels rotating at different speeds. Like projections in our modern planetariums, this model made it possible to accelerate the apparent movement of the planets along their trajectories and find patterns and certain speed ratios in it. To briefly explain how much we owe to the use of models, it suffices to recall that Bohr's atomic model played a key role in physics and that even a chemical experiment in a test tube or an experiment on rats in biology is an application of modeling techniques.

The first astronomical model was quite simple and unsophisticated, but for all its primitiveness, it was the progenitor of the modern planetarium, mechanical clocks, and many other related inventions. Anaximander suggested that the earth is disc-shaped, located in the center of the world and surrounded by hollow tubular rings ( modern chimney- a good semblance of what he had in mind) of different sizes, which rotate at different speeds. Each tubular ring is full of fire, but itself consists of a hard shell like a shell or bark (this shell Anaximander calls floyon), which allows the fire to burst out only from a few holes (breathing holes from which the fire bursts out as if blown by blacksmith bellows); these holes are what we see as the sun, moon and planets; they move across the sky as the circles revolve. Between the round wheels and the earth are dark clouds that cause eclipses: an eclipse occurs when they close the holes in the pipes from our eyes. This whole system as a whole rotates, making a revolution in one day, and, in addition, each wheel moves by itself.

It is not entirely clear whether this model had such an interpretation for fixed stars as well. It appears that Anaximander constructed the globe of the sky, but we do not know how this expansion of the technique of maps and models was connected with the moving mechanism of rings and fire.

Anaximander. First card

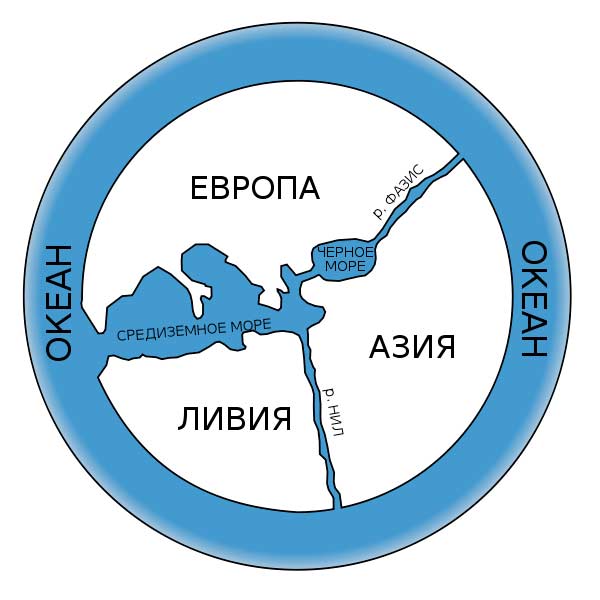

This map is a reconstruction of what is believed to be the first geographical map ever drawn. Its center is Delphi, where a stone called "the navel of the earth" (in Greek "omphalos") marked the exact center of the earth. The cartographer who created it was Anaximander, a Greek philosopher who lived from about 611 to 547 BC. e. Early maps were all round. Half a century later, Herodotus commented as follows: “I find it funny to see that so many people still draw maps of the Earth, but not one of them depicted it even tolerably: after all, they drew the Earth round, as if it were made with a compass, and surrounded it ocean river.

Anaximander's great contribution to science was the general conception of models, which he applied in the same way that we apply them now. In drawing the first map of the world known to him, he showed the same combination of technical ingenuity and scientific intuition. Just as a moving model can show the ratios of long astronomical periods on a smaller scale in which they are easy to observe and control, a map is a model of the distances between objects and their relative positions on a smaller scale, so that a person can capture it all at a glance; the map saves him from having to travel for long months or trying to sort through scattered notes where travelers described their routes in order to determine the location of places, distances and direction of movement.

The idea of a map is in itself an indication of the love of clarity and symmetry that was characteristic of Greek science and of later classical maps and models. Anaximander's world had the form of a circle centered on Delphi (where the sacred stone omphalos, as the Greeks believed, marked the exact center of the universe) and was surrounded by the ocean. Like the wheels - "chimneys", this map became the primitive ancestor of a huge offspring: it is the progenitor of maps and drawings that made possible the existence of modern navigation, survey work in geography and geology. The "Map of the Stars" is perhaps an even clearer example of how this original, scientific, ancient mind worked: the idea of mapping the sky instead of looking at the patterns the stars form as omens or ornaments implies, that terrestrial and celestial phenomena are of the same nature, and signifies an attempt to understand the world not through aesthetic fantasy and not through the irresponsible way of religious superstition.

But this use of models to duplicate the laws of nature under study, no matter how great their role has been over the centuries since then, is just a side addition to more common idea that nature is regular and predictable. Anaximander expressed this idea in his definition of natural law: "All things arise from the infinite ... they compensate each other for damage, and one pays the other for her guilt before her when she commits injustice, according to the account of time."

Although Anaximander seems to be repeating the ideas of high tragedy, in which "hybris" (excess of pride) inevitably leads to "nemesis" (fall-retribution), he speaks in purely legal language, borrowed from judicial practice, where the harm that one person causes to another , is compensated by the payment of money. Here he uses as a model for the periodic change of natural phenomena not a clock, but a pendulum. “All the things” that break the law in turn and pay the price for it are those opposite qualities that are “singled out” from the infinite. Events in nature, in fact, often take the form of a constant movement from one extreme state to another, opposite, and back; illustrative examples of this - ebb and flow, winter and summer. This movement became the model for Anaximander's "laws of nature": one quality tries to develop more than it should, displacing its opposite, and therefore "justice" throws it back, punishing for intrusion into someone else's territory. But over time, that of the opposites that lost at the beginning becomes stronger, in turn crosses the forbidden line and, "according to the account of time", must be returned to its legal limits.

This was a huge advance compared to the world of Thales, where the individual "psyches" of things were responsible for change and movement, although the tendency to endow everything with human properties and mythological thinking did not completely die out. From a historical point of view, it is interesting that the definition of the law of nature arose as a transfer to another area of \u200b\u200ba concept of judicial law already established in society: we would rather expect the opposite, since nature seems to us much more ordered than human society. However, the code of laws seemed to Anaximander the best model he could find to explain his new intuitive idea of exact periodicity and patterns of natural order.

The idea of evolution of Anaximander was led by acquaintance with the fossilized remains of fossil animals and observation of babies. High in the mountains of Asia Minor, he saw fossilized marine animals in the thickness of the stone. From this, he concluded that these mountains were once in the sea, under water, and that the level of the ocean was gradually lowering. We see what it was special case his law of alternation of opposites: spilling and drying up spilled water. He correctly reasoned that if once the whole earth was covered with water, then life must have originated in this ancient ocean. He said that the first and simplest animals were "sharks". We have no explanation why they were, but probably because, firstly, sharks seemed to him similar to the fossil fish that he saw, and, secondly, the very tough skin of sharks seemed to him a sign of primitiveness. Looking at human children - he had at least one son of his own - he came to the conclusion that no such helpless living creature could survive in nature without a protective environment. Life on land evolved from sea life: as the water dried up, the animals adapted to it by growing spiny hides. But people, because of their long helplessness in childhood, needed some additional process. But before this task, Anaximander was at an impasse: he could only assume that people, perhaps, developed inside the sharks and were released from them when the sharks died, and by that time they themselves had become more capable of independent living.

In his reflections on biological and botanical topics, Anaximander expressed another original idea: that in all nature beings that grow do so in the same way. They grow in concentric rings, the outermost of which hardens and turns into "bark" - tree bark, shark skin, dark shells around fiery wheels in the sky. It was a way to bring together developmental phenomena found separately in astronomy, zoology and botany; but this "shell" theory, unlike the other ideas we have considered here, has never been taken seriously. Later philosophers and men of science, from ancient Greeks to modern Americans, took either physics or zoology as their model of what science should be (extreme cases: respectively the simplest and most difficult subject to study). And Anaximander's statement is more like a generalizing conclusion from botany.

Anaximander, who combined the curiosity of a scientist, the rich imagination of a poet and the ingenious audacious intuition, can undoubtedly share with Thales the honor of standing at the origins of Greek philosophy. After Anaximander, Greek thinkers were able to see that the new questions posed by Thales implied something that went far beyond the answers offered by both Thales and Anaximander himself. We seem to see how science and philosophy froze for a moment in front of a new world that had just opened up for them - the world of abstract thought, which was waiting for its researchers.

The origins of European science and philosophy must be sought in Ancient Greece. It was there that the main approaches to understanding reality were born. One of the most ancient schools is the direction of natural philosophy of Thales of Miletus and his students. A prominent representative of this pre-Socratic period was Anaximander, whose philosophy belongs to the so-called elemental materialism. Let's talk about how the views of this philosopher differ. And also consider a brief biography of Anaximander and the main provisions of his philosophical and scientific views.

ancient greek philosophy

A small area on the Asia Minor coast of Ancient Greece, Ionia, is the birthplace of ancient, and hence European philosophy. This place was unique because it was at the crossroads of East and West. 12 famous Greek cities were located here, in which the culture of Ancient Greece was born. Numerous ships from the East were unloaded in the ports of Ionia. They brought to the cities not only goods, but also information about life in other countries, the knowledge that Eastern scientists had obtained, as well as foreign ideas about the structure and origin of the world. The inquisitive Greeks themselves visited the East a lot and could get acquainted with Indian, Persian, Egyptian religious and philosophical worldviews.

Under the influence of Eastern cultures, as well as due to the special socio-economic conditions in Greece, a new type of character is being formed. The Greeks respected other people's opinions and knowledge, were interested in the structure of the world and the causes of all things, and they were also characterized by common sense, a penchant for logical reasoning, and attentiveness to the world around them. At that time in the East there were already harmonious systems of ideas about how the world works, about the divine principles of life, about the meaning of human existence. There, ideas were formulated about the absolute beginning, about the divine origin of people and the world around, about the need for self-improvement and self-knowledge, about the moral foundations of human society. All this knowledge was taken up by representatives of the Milesian school, who also began to think about how the world works, what are its laws. So in the 6th century BC. e. ancient Greek philosophy began to take shape. This was not a borrowing of Eastern ideas, but original thinking, which included Eastern knowledge.

The main questions of ancient philosophy

The economic heyday of Ancient Greece, the emergence of Greek policies among free citizens a large number free time contributed to the development of ancient Greek art and philosophy. Unencumbered by the need to spend all their time and energy on survival, the Greeks began to think at their leisure about everything that surrounds them. In ancient Greece, an independent social stratum appeared - philosophers who led discussions, revealed to citizens the meaning of everything that exists. It was in such conditions that Anaximander lived, whose main ideas grew out of reflections on the main questions of being, which the ancient Greek philosophers set for themselves and the world. The main questions that interested people in ancient times include:

- Where did the world come from?

- What underlies the world?

- What is the main law of the world, logos?

- How can natural phenomena be explained?

- What is truth and how can it be known?

- What is a person and what place does he occupy in the world?

- What is the purpose of man, what is good?

- What is the meaning of human life?

- How is the soul arranged and where did it come from?

All these questions worried the Greeks, and they diligently sought answers to them. As a result, there were two main approaches to explaining the world and its origin: idealistic and materialistic. Philosophers have discovered the main ways of knowing: empirical, logical, sensual, rational. The earliest period of ancient philosophy is called natural philosophy, since in this era thinkers were most interested in the Cosmos and the world around them. Anaximander of Miletus also made a significant contribution to understanding these problems. In this regard, the main object of study in ancient philosophy is the origins of cosmology and cosmogony.

Milesian school

The very first scientific and philosophical school appeared in Greece at the beginning of the 6th century BC. e. It is called Milesian and belongs to the Ionic direction in ancient philosophy. The main representatives of the Milesian school are Thales and his students Anaximenes, Anaximander, Anaxagoras and Archelaus. Miletus in those days was a large, developed city, educated people came here not only from the coast of Asia Minor, but also from the countries of the East. Milesian philosophers were interested in how the world works, from which everything came. Milesian thinkers were the founders of many European sciences: physics, astronomy, biology, geography and, of course, philosophy. Their views were based on the thesis that nothing arises from nothing, and the idea that only the cosmos is eternal and infinite. Everything that a person sees around him has a divine origin, but primary sources lie at the basis of everything. The main reflections of Thales and his students, including the philosophy of Anaximander, were devoted to the problem of searching for the original primordial substance.

Thales and his students

Thales of Miletus is considered to be the founder of European science and ancient Greek philosophy. The years of his life are determined approximately: 640/624 - 548/545 BC. e. The Greeks revered Thales as the father of philosophy, he is included among the seven famous ancient Greek sages. His biography can be judged from different sources, the validity of which is not absolutely certain. It is believed that Thales was of Phoenician origin, he was from a noble family and received a good education. He was engaged in trade and sciences, traveled a lot, visited Egypt, Memphis, Thebes. He studied the causes of floods, mathematics, the experience of priests. Found a way to measure the height of the Egyptian pyramids. He is considered the founder of Greek geometry. There is no single version about the occupation of Thales in Greece. Some sources say that he was close to the local ruler and was involved in politics, according to another version, he lived ordinary life away from public affairs. The assumptions about his marital status also vary. According to some sources, he was married and had several children, according to others he was single and lived in solitude. Thales became famous after he predicted a solar eclipse in 585 BC. e. This is the only exact date that is known from the life of Thales.

The works of the scientist have not been preserved; in the Greek tradition, two main works are attributed to him: “On the Solstice” and “On the Equinoxes”. It is believed that he was the first to discover the constellation Ursa Major for the Greeks, and also made a number of astronomical discoveries. Answering the question about the primary world substance, he argued that the beginning of everything is water. She, in his opinion, is a living, active principle. When it hardens, dry land appears, and when it evaporates, air appears. The cause of all transformations of water is the spirit. Thales also has a number of accurate physical observations, as well as many fantastic assumptions. For example, he believed that the stars are made up of earth, and it, in turn, floats in water. The earth, in his opinion, is the center of the world, if it disappears, the whole world will collapse.

But the merit of Thales was that he tried to understand the structure of the universe, asked many important questions that laid the foundations of science. The activities of the scientist attracted several students to him, who formed the basis of the Milesian school of natural philosophy. There is no information left about the interaction of Thales with his followers, just as none of his works have been preserved. Today we learn about his thoughts and activities only from the memoirs of the next generations of scientists and thinkers, and there is no certainty in their accuracy. The closest students were Anaximenes and Anaximander. Philosophy has become a matter of life for them. The followers of this direction were Anaxagoras, Archelaus, who created their own schools of philosophy. Archelaus is considered the teacher of Socrates. Thus, the Milesian school became the foundation on which the whole philosophy of ancient Greece grew.

Anaximander: biography and interesting facts

Unfortunately, there is even less information about the students of Thales than about himself. Even whether Anaximander was actually a student of Thales has not been proven. Also, only approximately the years of Anaximander's life are known. He was born approximately in 610 BC. e., presumably in a wealthy merchant family. Contemporaries recall that he was engaged in a variety of activities: traded, traveled, engaged in science and reflection.

For some time he lived in Sparta. Anaximander of Miletus studied and state structure, it is known that he took part in the organization of one of the Milesian colonies. Like his teacher Thales, he studied natural phenomena and even predicted an earthquake in Sparta and saved many residents. He is also considered the founder of scientific geography. The philosopher lived for 55 years and died in the same year as his teacher Thales. There were many myths and legends, and even anecdotes about prominent people of early Greek history. Anaximander, interesting facts from whose life also turned into tales, is forever associated with the fact that he first drew a map of Greece on a sheet: “he dared to draw an oecumene,” as scientists of much later years wrote about him. He is also known as the first creator of the globe.

Treatise "On Nature"

The original tests of Anaximander have not been preserved; we learn about his works and thoughts from the later retellings of Greek scholars, as well as from the interpretations of early Christian scholars, who treated the primary sources very freely. Christian authors generally used quotations from the works of Anaximander solely to ridicule the pagan notions of the ancient Greeks. The only work of the philosopher that has come down to us is the treatise "On Nature". It is familiar to modern readers from paraphrases and the only surviving fragment of the original text. In this essay, the scientist outlined his thoughts about the structure of the world and its origin. His analysis shows that Anaximander went far from his teacher in his views on the Cosmos and its structure and was able to make many serious discoveries.

Cosmology of Anaximander

The main area of \u200b\u200bthought of the philosopher was connected with space. He believed that the stars are windows in the firmament. Inside the star, a fire burns, clad in shells.

Apparently, Anaximander, whose works are inaccessible to us for direct study, understood the structure of the Earth in a very peculiar way. He imagined her as a cylinder; we walk on one side, but there is another plane opposite to it. The earth is the center of the world, it does not rest on anything, but floats in space. The philosopher explained the reason for hovering by the fact that it is equidistant from all other objects in space. The earth is surrounded by giant rings with holes inside which fire burns. Small tubes end with stars, there is less fire in them, which is why the light of the stars is so dim. The second ring is larger and the fire in it is brighter, the Moon is visible through its hole. It sometimes overlaps - this is how the lunar phases are explained. The farthest ring is the brightest, and through its hole we see the Sun. Thus, the universe, according to Anaximander, ends with heavenly fire.

Anaximander's cosmological theory was incredibly innovative for its time. He placed the Earth at the center of the world, thus creating the first geocentric concept. She stands still, she has no reason to move. And the heavenly bodies move around the Earth in their orbits - in this way the scientist was able to explain the movement of space objects, which required powerful, unorthodox thinking.

Cosmogony of Anaximander

Reflections on the origin of the universe were also a big part of the scientist's activities. The philosophy of Anaximander was based on the denial of the participation of the Olympian gods in the creation of the universe. He believed that it develops on its own, according to its own laws, and it does not have a moment of occurrence, since the Cosmos is eternal. In his opinion, everything that exists begins to appear from some non-material beginning. At the first stage, everything is divided into physical entities: dry, wet, hard, soft, etc. The interaction of these substances forms the cosmos in the form of a ball, and already inside this shell various physical processes begin to occur. As a result of cooling, the earth and air around it appear, and hotter remains outside - fire. As a result of the influence of fire, the substance hardens so much that it creates a shell in which the universe exists. At the final stage of the formation of the universe, living beings appear. Anaximander believed that life originated in the remnants of the dried seabed. Moisture evaporates, and all living things are born from heat and silt. That is, he believed that there is a natural origin of life, without divine intervention. He also believed that the universe, like everything in the world, has its own life span, it is born, dies, and then reappears.

New ideas of Anaximander

In the field of cosmology, the scientist made many discoveries. His version that the earth stands motionless in the center of the world without any support was revolutionary for its time. Then all the thinkers still believed in the presence of the earth's axis, which holds the planet in place. The source of all things is something infinite, immaterial and eternal. The philosopher called this essence apeiron. This is a kind of substance that is elusive, as it is in constant motion. Apeiron constantly arises from something and transforms into something; it is incomprehensible to the human mind. The philosophical doctrine of Anaximander is built on the idea of apeiron as an attribute of something. In those days, this word was an adjective, only later Aristotle transforms it into a noun. From apeiron, as from a substrate, four elements appear, which organize everything that exists. The concepts of apeiron and substrate are the most important achievements of Anaximander. His ideas about the origin of all life without the participation of the gods became another innovative contribution to the baggage of human thought. These views will develop much later, already in modern times. The philosopher also became the progenitor of the dialectical approach to understanding the world. He talked about the fact that essences can flow into one another, wet things can dry out, and vice versa. He argued that the opposite has a single beginning, this became an anticipation of future dialectics.

Scientific views

One should remember the contribution of Anaximander to geography. In fact, he became the founder of this science in the European tradition. Thinking about the structure of the universe, he also thinks about how the earth works and tries to depict it graphically. Anaximander's land map is very naive: three continents - Europe, Asia and Libya - are washed by the ocean. And they are separated by the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. He was the first European to draw a map of his world (it has not been preserved, we can judge it only by fragments). Of course, so far there are very few geographical objects on it, but this was already a breakthrough, since the next generations of scientists and travelers were able to expand and supplement this map.

Another important scientific achievement of Anaximander is the installation of the first gnomon in Greece - a sundial and the improvement of the skafis, the Babylonian clock. Among the astronomical achievements of Anaximander, whose discoveries were a breakthrough for his time, one can name an attempt to compare the magnitudes of known celestial bodies with the Earth.

Disciples of Anaximander: Anaximenes

Anaximander became one of the important steps in the evolution of ancient Greek philosophy. His main student Anaximenes continued and developed the views of his teacher, he also belongs to the Milesian school. The main merit of the philosopher in the continuation of reflections on the movement of the universe. As the fundamental principle of all things, he put forward air. He is unlimited and has no qualities. Its particles interact with each other, and from here everything that exists is born, the characteristics of the material world appear. Anaximenes became the closing link in the flow of spontaneous materialism.

He wrote a philosophical work in prose, one excerpt from which has come down to us in the transmission of Theophrastus. The doxographer writes: “Of those who taught about the one, moving and infinite [beginning], Anaximander ... said that the beginning and element of being is the infinite, the first to use such a name for the beginning. He says that the beginning is neither water, nor any of the so-called elements in general, but some other infinite nature from which all the heavens and all the worlds in them arise. “And from what [beginnings] existent [things] arise, into the same they are destroyed according to necessity. For they bear punishment and receive retribution from one another for their wickedness, according to the order of time,” he says in overly poetic terms. Obviously, noticing that the four elements turn into one another, he did not consider it possible to recognize any one of them as a substratum, but accepted something different from them. The emergence of things does not come from a qualitative change in the elements, but as a result of the separation of opposites due to perpetual motion ... Opposites are warm, cold, dry, wet, etc. ” (DK 12 A 9, V 1).

Anaximander. Fragment of Raphael's painting "The School of Athens", 1510-1511

This fragment from Theophrastus' Opinions of the Physicists, preserved in the text of Symplicius's commentary on Aristotle's Physics and, in turn, containing a fragment of Anaximander, caused a fierce controversy. First of all, regarding the volume of the fragment. The minimum is limited to the words: “... according to need. For they bear punishment and receive retribution from one another.” The preceding part of the text of the fragment adopted by Diels is regarded as a stereotyped description of the general position of the "physiologists" borrowed from Aristotle; the next one is like a theophrastic paraphrase of Anaximander's text. And yet, even if we reduce the original text of Anaximander to this obscure passage, Theophrastus gives a lot.

(one). There is no doubt that Anaximander recognized the "beginning" of being as something unified and boundless (infinite, indefinite - to apeiron). It is possible that he introduced this name, "apeiron", as according to a long and venerable tradition, the "original principle" of Anaximander is called. However, it is possible that this is a term that does not belong to him himself, but developed by doxography.

(2). According to the logic of Theophrastus, who sees a monist in Anaximander, the phrase “And from which ... to the same ones” should have been in singular(from the infinite... to the infinite). It is also in the plural (ex hon ... eis tayta), which testifies to the authenticity, if not of the text, then of the thought expressed by it. Theophrastus' subsequent explanation shows that plural most likely refers to the "opposites", as a result of the isolation of which things are formed.

(3). Anaximander's appeal to the "infinite" is interesting in that to apeiron can mean both qualitatively indefinite and quantitatively infinite. So, we have conflicting evidence about Thales. In one place, Simplicius says that Thales recognized his beginning - water - as final. In another place, he writes: “those who took any one element as a basis, considered it infinite in magnitude, like Thales, for example, water” (DK R A 13). For his part, Aristotle argued that "none of the physicists did not make fire or earth single and infinite, but only water, air, or the middle between them" (Phiz, III, 5, 205a). From this we can conclude that the first evidence of Simplicius speaks of the qualitative certainty of the Thales "beginning" (water), and the second - of quantitative infinity, as the doxographer writes. Anaximander then turns out to be a man who introduces the concept of a qualitatively indefinite and quantitatively infinite beginning. The birth of things from it is their qualitative definition and limitation.

(4). Sometimes Anaximander's "infinite" is identified with the mythological Chaos. But this is contradicted by the recognition of the temporal orderliness of emergence and destruction, moreover, the necessary orderliness.

Is it possible to go further? It is sometimes believed that Anaximander's "infinite" is "infinite in general", a concept formed by abstraction from everything concrete. However, Aristotle specifically stipulated that this was not the case. The recognition of the infinite or the infinite as such is peculiar only to the Pythagoreans and Plato, while “natural philosophers (“physicists”) always consider as the carrier of infinity some other nature from the so-called elements, for example, water, air, or the average between them” (Phys., III, 4, 203a). This clearly applies to Anaximander, and his "other nature" - the bearer of the predicate of infinity (infinity) - should be characterized in some way. The following points of view are usually put forward on this matter: firstly, it can be an “indefinite nature”, which in principle does not allow definition; secondly, the future "matter" (hyle) of Plato and Aristotle, potentially containing all things, but devoid of actual qualities and subject to registration from the side of the ideal beginning, "idea" or "form"; thirdly, a mechanical mixture of all things or elements, from which things are then separated; finally - something "middle" between elements or elements (metaxy).

Each of these solutions, relying on certain evidence from Aristotle and doxographers, has its weak points. "Indeterminate nature" (physis aoristos) is hardly a solution at all, since it is a purely negative concept. Meanwhile, Anaximander has specific definitions of the "substance of the infinite." We will talk about them below. The same can be said about "matter" in the sense of Aristotle and Plato. They characterize "matter" as "non-existence" (me on Plato), as pure possibility and "deprivation". But this view is incompatible with the fact that Anaximander's "infinite" is an active creative force that "rules everything." He completely lacks an idea of the “idea” external to the beginning, in relation to which the “infinite” would act as “nature that is different from the idea” (Plato. Parmenides, 158c). “Mixture” is a characteristic of the beginning, which belongs to physiologists of the 5th century, in particular to Anaxagoras. But even if the original mixture can be represented as a single and homogeneous mass, then it can no longer be understood in the sense of a living, organic whole, the "nature" of the early Greek philosophers. Most likely, perhaps, the fourth solution. But even here there is no certainty. In various places in Aristotle's writings, without reference to the name (or names?) of a thinker who holds one point of view or another, the "infinite" is spoken of as the mean between fire and air or between air and water. The context in all these cases suggests the name of Anaximander, but some other name, unknown to us, is not excluded. In any case, the question of whether apeiron belongs to Anaximander as a metaxy remains open.

However, we can speak with good reason about the following "properties" of the Anaximander principle. As Aristotle says, it does not arise and is not destroyed, “it does not have a beginning, but it itself appears to be a beginning, encompasses everything and governs everything, as those say who do not recognize other fundamental causes besides the infinite... And it is divine, for immortal and indestructible as Anaximander and most natural philosophers say” (Phys. III, 4, 203 b). Hippolytus retained a slightly different characterization: Anaximander's boundless "eternal and ageless" (DK 12 A 11). Finally, we read from Plutarch: “... Anaximander ... argued that the whole reason for the universal emergence and destruction lies in the infinite ... When our world arose from the eternal [beginning], something capable of producing hot and cold stood out, and formed from it the fiery sphere enveloped the air surrounding the earth, just as the bark envelops a tree. When the fiery sphere broke through and closed into several rings, the sun, moon and stars arose” (DK 12 A 10).

Based on these evidence, one can construct the following scheme of changes in the apeiron that generates things: the eternal, ageless, immortal and indestructible "infinite nature", or "nature of the infinite" - apeiron - highlights the "producing beginning" (to gonimon - perhaps the term of Anaximander himself , formed similarly to apeiron), giving rise to the opposites of warm and cold, dry and wet, from which, in turn, things are formed. Unfortunately, one can only guess what is the meaning of the relationship of opposites, expressed by the words "... they are punished and receive retribution from each other", but here the dialectic of the struggle, the clash of opposite principles, which will flourish in Heraclitus, is clearly emerging.

Summing up the exposition of the philosophical teachings of Anaximander, let us say that in it, although “in too poetic terms” (Theophrastus), the most important features of the “beginning” are formulated in prose (arche - it is possible that the term itself was introduced in this sense by Anaximander, although Theophrastus' indication of this fact is now disputed): its all-encompassing, creative and productive character, its eternity and indestructibility in contrast to finite, arising and perishing things and worlds, its infinity in time and space, like the eternity of its movement, its internal necessity and self-direction. Hence its "divinity" as the highest value characteristic of the "infinite". Finally, although it is hardly possible to say with certainty that everything consists of apeiron, it is certain that everything comes from it (is born) and everything returns to it again, dying. Here we are even further from the myth than in the case of Thales, and there is no doubt that the concrete scientific ideas of Anaximander played their role in this.

The content of these concepts is as follows. Anaximander is credited with the invention of the sundial, the compilation of the first geographical map among the Greeks, and the systematization of geometric statements. But, of course, the cosmology and cosmogony of Anaximander, restored according to the testimonies of the ancients, are of paramount importance. Picture of the world, according to Anaximander, in in general terms is. The earth, like a cylindrical section of a column or a drum, whose height is equal to one third of the width, rests in the center of the world "due to the equal distance from everywhere" (A 11). Above the Earth (the question of whether it arises from the “encompassing” (apeiron) or exists forever remains open) there are, in the process of the formation of the “sky”, water and air shells, then a shell of fire. When the fiery sphere breaks, it simultaneously closes into several rings surrounded by dense air. In the air shell of the rings there are holes, through which the fire is visible and appears to us as luminaries. Eclipses of the Sun, as well as the phases of the Moon, are explained by the opening and closing of these openings. Above all is the solar ring (it is 27 times larger than the Earth), below is the lunar ring (19 times larger than it), just below is the stellar one. There are an infinite number of worlds, but it is not clear from the evidence whether they replace each other in the course of the eternal circulation “in the order of time” or whether they coexist.

The earth was originally covered with water. The latter gradually dries up, and the water remaining in the recesses forms the sea. Drying out from excessive heat or soaking due to heavy rains, the earth forms cracks, penetrating into which the air moves it from its place - this is how earthquakes occur. The first animals arose in a humid place (in the sea) and were covered with prickly scales. When they reached a certain age, they began to go out onto land, and from them terrestrial animals and people arose. This is how Anaximander's global outlook is concretized. Here, as in all the first philosophical teachings, fantastic attitudes borrowed from mythology are combined with attempts at rational (including mathematical) “decoding” of them. The result is a striking synthesis that is not reducible to these original constituent elements.

Ancient Greek philosophy.

Milesian school: Thales, Anaximander and Anaximenes

- Find the invisible unity of the world -

The specificity of ancient Greek philosophy, especially in the initial period of its development, is the desire to understand the essence of nature, space, the world as a whole. Early thinkers are looking for some origin from which everything came. They consider the cosmos as a continuously changing whole, in which the unchanging and self-identical origin appears in various forms experiencing all sorts of transformations.

The Milesians made a breakthrough with their views, in which the question was clearly posed: “ What is everything from?» Their answers are different, but it was they who laid the foundation for the actual philosophical approach to the question of the origin of beings: to the idea of substance, that is, to the fundamental principle, to the essence of all things and phenomena of the universe.

The first school in Greek philosophy was founded by the thinker Thales, who lived in the city of Miletus (on the coast of Asia Minor). The school was named Milesian. The disciples of Thales and the successors of his ideas were Anaximenes and Anaximander.

Thinking about the structure of the universe, the Milesian philosophers said the following: we are surrounded by completely different things (essences), and their diversity is infinite. None of them is like any other: a plant is not a stone, an animal is not a plant, the ocean is not a planet, air is not fire, and so on ad infinitum. But after all, despite this variety of things, we call everything that exists the surrounding world or the universe, or the Universe, thereby assuming the unity of all things. The world is still one and whole, which means that the world's diversity there is a certain common basis, the same for all different entities. Despite the difference between the things of the world, it is still one and whole, which means that the world's diversity has a certain common basis, the same for all different objects. Behind the visible diversity of things lies their invisible unity. Just as there are only three dozen letters in the alphabet, which generate millions of words through all sorts of combinations. There are only seven notes in music, but their various combinations create an immense world of sound harmony. Finally, we know that there is a relatively small set of elementary particles, and their various combinations lead to an infinite variety of things and objects. These are examples from modern life and they could be continued; the fact that different things have the same basis is obvious. The Milesian philosophers correctly grasped this regularity of the universe and tried to find this basis or unity, to which all world differences are reduced and which unfolds into an infinite world diversity. They sought to calculate the basic principle of the world, ordering and explaining everything, and called it Arche (the beginning).

The Milesian philosophers were the first to express a very important philosophical idea: what we see around us and what really exists are not the same thing. This idea is one of the eternal philosophical problems - what is the world in itself: the way we see it, or is it completely different, but we do not see it and therefore do not know about it? Thales, for example, says that we see various objects around us: trees, flowers, mountains, rivers, and much more. In fact, all these objects are different states of one world substance - water. A tree is one state of water, a mountain is another, a bird is a third, and so on. Do we see this single world substance? No, we do not see; we see only its state, or production, or form. How then do we know what it is? Thanks to the mind, for what cannot be perceived by the eye can be comprehended by thought.

This idea about the different abilities of the senses (sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste) and the mind is also one of the main ones in philosophy. Many thinkers believed that the mind is much more perfect than the senses and more capable of knowing the world than the senses. This point of view is called rationalism (from Latin rationalis - reasonable). But there were other thinkers who believed that one should trust the senses (sense organs) to a greater extent, and not the mind, which can fantasize anything and therefore is quite capable of being mistaken. This point of view is called sensationalism (from Latin sensus - feeling, feeling). Please note that the term “feelings” has two meanings: the first is human emotions (joy, sadness, anger, love, etc.), the second is the sense organs with which we perceive the world around us (sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste). On these pages it was about feelings, of course, in the second meaning of the word.

From thinking within the framework of myth (mythological thinking), it began to be transformed into thinking within the framework of logos (logical thinking). Thales freed thinking both from the fetters of mythological tradition and from the chains that tied it to direct sensory impressions.

It was the Greeks who managed to develop the concepts of rational proof and theory as its focus. The theory claims to receive a generalizing truth, which is not simply proclaimed from nowhere, but appears through argumentation. At the same time, both the theory and the truth obtained with its help must withstand public tests of counterarguments. The Greeks had the ingenious idea that one should look for not only collections of isolated fragments of knowledge, as was already done on a mythical basis in Babylon and Egypt. The Greeks began to search for universal and systematic theories that substantiated individual fragments of knowledge from the point of view of generally valid evidence (or universal principles) as the basis for the conclusion of specific knowledge.

Thales, Anaximander and Anaximenes are called Milesian natural philosophers. They belonged to the first generation of Greek philosophers.

Miletus is one of the Greek policies located on the eastern border of the Hellenic civilization, in Asia Minor. It was here that the rethinking of mythological ideas about the beginning of the world first of all acquired the character of philosophical reasoning about how the diversity of phenomena surrounding us arose from one source - the primordial element, the beginning - arche. It was natural philosophy, or the philosophy of nature.

The world is unchanging, indivisible and immovable, represents eternal stability and absolute stability.

Thales (7th-6th centuries BC)

1. Everything starts from water and returns to it, all things originated from water.

2. Water is the essence of every single thing, water is in all things, and even the sun and heavenly bodies are nourished by the vapors of water.

3. The destruction of the world after the expiration of the "world cycle" will mean the immersion of all things in the ocean.

Thales argued that "everything is water." And with this statement, as it is believed, philosophy begins.

Thales (c. 625-547 BC) - the founder of European science and philosophy

Thales pushing the idea of substance - the fundamental principle of everything , having generalized all the diversity into a consubstantial and seeing the beginning of everything is in WATER (in moisture): because it permeates everything. Aristotle said that Thales first tried to find a physical beginning without the mediation of myths. Moisture is indeed an ubiquitous element: Everything comes from water and turns into water. Water as a natural principle is the carrier of all changes and transformations.

In the position “everything from water”, the Olympian, that is, pagan, gods were “resigned”, ultimately mythological thinking, and the path to a natural explanation of nature was continued. What else is the genius of the father of European philosophy? He first came up with the idea of the unity of the universe.

Thales considered water to be the basis of all things: there is only water, and everything else is its creations, forms and modifications. It is clear that its water is not quite similar to what we mean by this word today. He has her a certain universal substance from which everything is born and formed.

Thales, like his successors, stood on the point of view hylozoism- the view that life is an immanent property of matter, being itself is moving, and at the same time animated. Thales believed that the soul is poured into everything that exists. Thales considered the soul as something spontaneously active. Thales called God the universal intellect: God is the mind of the world.

Thales was a figure who combined an interest in the demands of practical life with a deep interest in questions about the structure of the universe. As a merchant, he used trade trips to expand his scientific knowledge. He was a hydroengineer, famous for his work, a versatile scientist and thinker, an inventor of astronomical instruments. As a scientist, he became widely famous in Greece, making a successful prediction of a solar eclipse observed in Greece in 585 BC. e. For this prediction, Thales used the astronomical information he obtained in Egypt or in Phoenicia, which goes back to the observations and generalizations of Babylonian science. Thales tied his geographical, astronomical and physical knowledge into a coherent philosophical idea of the world, materialistic at the core, despite clear traces of mythological ideas. Thales believed that the existing arose from some kind of wet primary substance, or "water". Everything is constantly born from this “single source. The Earth itself rests on water and is surrounded on all sides by the ocean. She is on the water, like a disk or a board floating on the surface of a reservoir. At the same time, the material principle of “water” and all the nature that originated from it are not dead, not devoid of animation. Everything in the universe is full of gods, everything is animated. Thales saw an example and proof of universal animation in the properties of a magnet and amber; since the magnet and amber are able to set bodies in motion, therefore, they have a soul.

Thales belongs to an attempt to understand the structure of the universe surrounding the Earth, to determine in what order the celestial bodies are located in relation to the Earth: the Moon, the Sun, the stars. And in this matter, Thales relied on the results of Babylonian science. But he imagined the order of the luminaries to be the reverse of that which exists in reality: he believed that the closest to the Earth is the so-called sky of fixed stars, and the farthest away is the Sun. This error was corrected by his successors. His philosophical view of the world is full of echoes of mythology.

“Thales is believed to have lived between 624 and 546 BC. Part of this assumption is based on the statement of Herodotus (c. 484-430/420 BC), who wrote that Thales predicted a solar eclipse of 585 BC.

Other sources report Thales traveling through Egypt, which was quite unusual for the Greeks of his time. It is also reported that Thales solved the problem of calculating the height of the pyramids by measuring the length of the shadow from the pyramid when his own shadow was equal to the size of his height. The story that Thales predicted a solar eclipse indicates that he possessed astronomical knowledge that may have come from Babylon. He also had knowledge of geometry, a branch of mathematics that had been developed by the Greeks.

Thales is said to have taken part in the political life of Miletus. He used his mathematical knowledge to improve navigation equipment. He was the first to accurately determine the time using a sundial. And, finally, Thales became rich by predicting a dry lean year, on the eve of which he prepared in advance, and then profitably sold olive oil.

Little can be said about his works, since all of them have come down to us in transcriptions. Therefore, we are compelled to adhere in their presentation to what other authors report about them. Aristotle in Metaphysics says that Thales was the founder of this kind of philosophy, which raises questions about the beginning, from which everything that exists, that is, that which exists, and where everything then returns. Aristotle also says that Thales believed that such a beginning is water (or liquid).

Thales asked questions about what remains constant in change and what is the source of unity in diversity. It seems plausible that Thales proceeded from the fact that changes exist and that there is some kind of one beginning that remains a constant element in all changes. It is building block universe. Such a "permanent element" is usually called the first principle, the "primal foundation" from which the world is made (Greek arche)."

Thales, like others, observed many things that arise from water and that disappear in water. Water turns into steam and ice. Fish are born in water and then die in it. Many substances, like salt and honey, dissolve in water. Moreover, water is essential for life. These and similar simple observations could lead Thales to assert that water is a fundamental element that remains constant in all changes and transformations.

All other objects arise from water, and they turn into water.

1) Thales raised the question of what is the fundamental "building block" of the universe. Substance (original) represents an unchanging element in nature and unity in diversity. Since that time, the problem of substance has become one of the fundamental problems of Greek philosophy;

2) Thales gave an indirect answer to the question of how changes occur: the fundamental principle (water) is transformed from one state to another. The problem of change also became another fundamental problem of Greek philosophy."

For him, nature, physis, was self-moving ("living"). He did not distinguish between spirit and matter. For Thales, the concept of "nature", physis, seems to have been very broad and most closely related modern concept"being".

Raising the question of water as the only foundation of the world and the beginning of all things, Thales thereby solved the question of the essence of the world, all the diversity of which is derived (originates) from a single basis (substance). Water is what subsequently many philosophers began to call matter, the "mother" of all things and phenomena of the surrounding world.

Anaximander (c. 610 - 546 BC) the first to rise to original idea infinity worlds. For the fundamental principle of existence, he took apeiron — indefinite and infinite substance: its parts change, but the whole remains unchanged. This infinite principle is characterized as a divine, creative and moving principle: it is inaccessible to sensory perception, but is comprehensible by reason. Since this beginning is infinite, it is inexhaustible in its possibilities for the formation of concrete realities. This is an ever-living source of neoplasms: everything in it is in an indefinite state, as real opportunity. Everything that exists is, as it were, scattered in the form of tiny slices. So small grains of gold form whole ingots, and particles of earth form its concrete arrays.

Apeiron is not associated with any specific substance, it gives rise to a variety of objects, living beings, people. Apeiron is boundless, eternal, always active and in motion. Being the beginning of the Cosmos, apeiron distinguishes from itself opposites - wet and dry, cold and warm. Their combinations result in earth (dry and cold), water (wet and cold), air (wet and hot), and fire (dry and hot).

Anaximander expands the concept of the beginning to the concept of "arche", i.e., to the beginning (substance) of everything that exists. This beginning Anaximander calls apeiron. The main characteristic of apeiron is that it " boundless, limitless, endless ". Although apeiron is material, nothing can be said about him, except that he "does not know old age", being in eternal activity, in perpetual motion. Apeiron is not only substantial, but also genetic origin space. He is the only cause of birth and death, from which the birth of everything that exists, at the same time disappears of necessity. One of the fathers of the Middle Ages complained that Anaximander "left nothing to the divine mind" with his cosmological concept. Apeiron is self-sufficient. He embraces everything and controls everything.

Anaximander decided not to name the fundamental principle of the world by the name of any element (water, air, fire or earth) and considered the only property of the original world substance, which forms everything, its infinity, omnipotence and irreducibility to any particular element, and therefore - uncertainty. It stands on the other side of all the elements, all of them includes and is called Apeiron (Boundless, infinite world substance).

Anaximander recognized that the single and constant source of the birth of all things was no longer “water” and not any separate substance in general, but the primary substance from which the opposites of warm and cold are separated, giving rise to all substances. It is a principle different from other substances (and in this sense indefinite), has no boundaries and therefore there is boundless» (apeiron). After the isolation of the warm and cold from it, a fiery shell arose, cloaking the air above the earth. The inflowing air broke through the fiery shell and formed three rings, inside of which a certain amount of fire broke out. So there were three circles: the circle of the stars, the sun and the moon. The earth, similar in shape to the cut of a column, occupies the middle of the world and is motionless; animals and people formed from the sediments of the dried seabed and changed forms when they moved to land. Everything detached from the infinite must return to it for its “guilt”. Therefore, the world is not eternal, but after its destruction, a new world emerges from the infinite, and this change of worlds has no end.

Only one fragment attributed to Anaximander has survived to our times. In addition, there are comments by other authors, such as Aristotle, who lived two centuries later.

Anaximander did not find a convincing basis for the assertion that water is an unchanging fundamental principle. If water is transformed into earth, earth into water, water into air, and air into water, etc., this means that anything is transformed into anything. Therefore, it is logically arbitrary to say that water or earth (or whatever) is "the first principle." Anaximander preferred to assert that the fundamental principle is apeiron (apeiron), indefinite, boundless (in space and time). In this way, he apparently avoided objections similar to those mentioned above. However, from our point of view, he "lost" something important. Namely, unlike water apeiron is not observable. As a result, Anaximander must explain the sensible (objects and the changes occurring in them) with the help of the sensually imperceptible apeiron. From the point of view of experimental science, such an explanation is a shortcoming, although such an assessment is, of course, an anachronism, since Anaximander hardly had a modern understanding of the empirical requirements of science. Perhaps most important for Anaximander was to find a theoretical argument against Thales' answer. And yet Anaximander, analyzing the universal theoretical statements of Thales and demonstrating the polemical possibilities of their discussion, called him "the first philosopher."

The Cosmos has its own order, not created by the gods. Anaximander suggested that life originated on the border of the sea and land from silt under the influence of heavenly fire. Over time, man also descended from animals, having been born and developed to an adult state from fish.

Anaximenes (c. 585-525 BC) believed that the origin of all things is air ("apeiros") : all things come from it by condensation or rarefaction. He thought of it as infinite and saw in it the ease of change and transmutability of things. According to Anaximenes, all things arose from the air and are its modifications, formed by its condensation and discharge. Discharging, the air becomes fire, condensing - water, earth, things. Air is more formless than anything. He is less body than water. We do not see it, but only feel it.

The rarefied air is fire, the thicker air is atmospheric, even thicker is water, then earth, and finally stones.

The last in the line of Milesian philosophers, Anaximenes, who had reached maturity by the time of the conquest of Miletus by the Persians, developed new ideas about the world. Taking air as the primary substance, he introduced a new and important idea about the process of rarefaction and condensation, by which all substances are formed from the air: water, earth, stones and fire. “Air” for him is a breath that embraces the whole world. just as our soul, being the breath, holds us. By its nature, "air" is a kind of vapor or dark cloud and is akin to emptiness. The earth is a flat disk supported by air, just as the flat disks of luminaries hovering in it, consisting of fire. Anaximenes corrected the teachings of Anaximander on the order of the arrangement of the Moon, the Sun and the stars in world space. Contemporaries and subsequent Greek philosophers gave Anaximenes more importance than other Milesian philosophers. The Pythagoreans adopted his teaching that the world breathes air (or emptiness) into itself, as well as some of his teaching about heavenly bodies.

Only three small fragments have survived from Anaximenes, one of which is probably not genuine.

Anaximenes, the third natural philosopher from Miletus, drew attention to another weakness in the teachings of Thales. How is water transformed from its undifferentiated state into water in its differentiated states? As far as we know, Thales did not answer this question. As an answer, Anaximenes argued that the air, which he considered as the "primordial principle", condenses into water when cooled, and condenses into ice (and earth!). When heated, air liquefies and becomes fire. Thus, Anaximenes created a certain physical theory of transitions. Using modern terms, it can be argued that, according to this theory, different aggregate states (steam or air, actually water, ice or earth) are determined by temperature and density, changes in which lead to abrupt transitions between them. This thesis is an example of the generalizations so characteristic of the early Greek philosophers.

Anaximenes points to all four substances, which were later "called" four principles (elements) ". These are earth, air, fire and water.

The soul also consists of air."Just as our soul, being air, restrains us, so breath and air embrace the whole world." Air has the property of infinity. Anaximenes associated its condensation with cooling, and rarefaction - with heating. Being the source of both the soul and the body, and the entire cosmos, air is primary even in relation to the gods. The gods did not create the air, but they themselves from the air, just like our soul, the air supports everything and controls everything.

Summarizing the views of the representatives of the Milesian school, we note that philosophy here arises as a rationalization of myth. The world is explained on the basis of itself, on the basis of material principles, without the participation of supernatural forces in its creation. The Milesians were hylozoists (Greek hyle and zoe - matter and life - a philosophical position, according to which any material body has a soul), i.e. they talked about the animation of matter, believing that all things move due to the presence of a soul in them. They were also pantheists (Greek pan - everything and theos - God - a philosophical doctrine, according to which "God" and "nature" are identified) and tried to identify natural content gods, meaning by this actually natural forces. In man, the Milesians saw, first of all, not biological, but physical nature, deducing him from water, air, apeiron.

Alexander Georgievich Spirkin. "Philosophy." Gardariki, 2004.

Vladimir Vasilievich Mironov. "Philosophy: Textbook for universities." Norma, 2005.

Dmitry Alekseevich Gusev. "A Brief History of Philosophy: A Not Boring Book." NC ENAS, 2003.

Igor Ivanovich Kalnoy. "Philosophy for Graduate Students."

Valentin Ferdinandovich Asmus. "Ancient philosophy." graduate School, 2005.

Skirbekk, Gunnar. "History of Philosophy."

MILETE SCHOOL

the first naive-materialistic and spontaneous dialectic. the school of ancient Greek philosophy represented by Thales, Anaximander and Anaximenes. It received its name after the city of Miletus in Ionia (the western coast of M. Asia), which bloomed in the 6th century. BC. economic center. In Miletus, the rapid development of crafts and trade caused the rise of trade and industry. class, to-ry, getting stronger economically, won the main. positions in politics. the life of the polis. Along with the fall of the power of the tribal aristocracy, their traditions began to play an ever smaller role. representation. Ordinary religious-mythological. ideas about the gods as the external causes of everything that happens in the world did not meet the needs of a person striving for nature. explanation of the phenomena of reality. There is doubt about the authenticity of the myths. The development of mathematical, astronomical, geographical. and other knowledge is explained by the general rise of all aspects of society. life, incl. the development of trade, navigation, crafts and construction. affairs, as well as using the achievements of Eastern science.

All the Milesian philosophers are spontaneous materialists; for them, the single essence ("the beginning") of the diverse phenomena of nature lies "in something definitely bodily", for Thales this essence is water, for Anaximander it is an indefinite and boundless primordial substance (apeiron), for Anaximenes it is air. In the views of philosophers M. sh. about the origin and laws of existence are affected by aesthetic. perception of the world, related activity of arts. imagination and figurative thinking, remnants of mythological, anthropomorphic. and hylozoistic. representations.

The Milesian school for the first time abolished the mythological picture of the world, based on the axiologization of the concepts of top-bottom and the opposition of the heavenly (divine) to the earthly (human) (Arist. De caelo 270a5), and introduced the universality of physical laws (a line that Aristotle could not cross). Fundamental to all Milesian theories remains the law of conservation (ex nihil nihil), or the denial of absolute “emergence” and “annihilation” (“birth” and “death”) as anthropomorphic categories (Anaximander, fi; B l; Arist. Met. 983b6).

Anaximander of Miletus(ancient Greek Ἀναξίμανδρος, 610 - 547/540 BC) - an ancient Greek philosopher, a representative of the Milesian school of natural philosophy, a student of Thales of Miletus and teacher of Anaximenes. Author of the first Greek scientific work written in prose ("On Nature", 547 BC). Introduced the term "law", applying the concept of social practice to nature and science. Anaximander is credited with one of the first formulations of the law of conservation of matter (“from the same things from which all existing things are born, into these same things they are destroyed according to their destiny”).

Cosmology

Anaximander considered the celestial bodies not as separate bodies, but as “windows” in opaque shells that hide fire. The earth looks like a part of a column - a cylinder, the diameter of the base of which is three times the height: "from two [flat] surfaces, we walk along one, and the other is opposite to it."

The earth floats in the center of the world, not leaning on anything. The earth is surrounded by gigantic tubular rings-tori filled with fire. In the closest ring, where there is little fire, there are small holes - stars. In the second ring with stronger fire there is one large hole - the Moon. It can partially or completely overlap (this is how Anaximander explains the change of lunar phases and lunar eclipses). In the third, farthest ring, there is the largest hole, the size of the Earth; through it shines the strongest fire - the Sun. The universe of Anaximander closes the heavenly fire.

Anaximander's system of the world (one of the modern reconstructions)

Thus, Anaximander believed that all heavenly bodies are at different distances from the Earth. Apparently, the sequence corresponds to the following physical principle: the closer it is to heavenly fire and, therefore, the farther from the Earth, the brighter it is. According to modern reconstruction, the inner and outer diameters of the Sun's ring, according to Anaximander, are respectively 27 and 28 diameters of the Earth's cylinder, for the Moon these values are 18 and 19 diameters, for stars 9 and 10 diameters. Anaximander's universe is based on a mathematical principle: all distances are multiples of three.

In Anaximander's system of the world, the paths of celestial bodies are whole circles. This point of view, now quite obvious, was innovative in the time of Anaximander. This first in the history of astronomy geocentric model of the Universe with the orbits of the stars around the Earth made it possible to understand the geometry of the movements of the Sun, Moon and stars.

The Universe is thought to be centrally symmetrical; hence the Earth, which is at the center of the Cosmos, has no reason to move in any direction. Thus, Anaximander was the first to suggest that the Earth rests freely in the center of the world without support.

Cosmogony

Anaximander sought not only to accurately describe the world geometrically, but also to understand its origin. In the work "On Nature", known from retellings and the only surviving fragment, Anaximander gives a description of the Cosmos from the moment of its origin to the origin of living beings and man.

The universe, according to Anaximander, develops on its own, without the intervention of the Olympian gods. Anaximander believes that the source of the origin of all things is a certain infinite, "ageless" [divine] principle - apeiron (ἄπειρον) - which is characterized by continuous movement. The apeiron itself, as that from which everything arises and into which everything turns, is something permanently abiding and indestructible, boundless and infinite in time.

Apeiron, as a result of a vortex-like process, is divided into physical opposites of hot and cold, wet and dry, etc., the interaction of which generates a spherical cosmos. The confrontation of the elements in the emerging cosmic vortex leads to the appearance and separation of substances. In the center of the vortex is "cold" - the Earth, surrounded by water and air, and outside - fire. Under the influence of fire, the upper layers of the air shell turn into a hard crust. This sphere of solidified aer (ἀήρ, air) begins to burst with vapors of the boiling earth's ocean. The shell does not hold up and swells ("tear off", as stated in one of the sources). At the same time, it must push the bulk of the fire beyond the boundaries of our world. This is how the sphere of fixed stars arises, and the pores in the outer shell become the stars themselves. Moreover, Anaximander claims that things acquire their being and composition for a time, “in debt”, and then, according to the law, at a certain time, they return their due to the principles that gave birth to them.

The final stage in the emergence of the world is the appearance of living beings. Anaximander suggested that all living things originated from the sediments of the dried seabed. All living things are generated by moisture evaporated by the sun; when the ocean boils away, exposing the land, living beings arise "from the heated water with the earth" and are born "in moisture, enclosed within a silty shell." That is, natural development, according to Anaximander, includes not only the emergence of the world, but also the spontaneous generation of life.

Anaximander considered the universe to be like a living being. Unlike ageless time, it is born, reaches maturity, grows old and must die in order to be reborn: “... the death of the worlds takes place, and much earlier their birth, and from time immemorial, the same thing is repeated in a circle.”