We remember Chapaev from books and films, we tell jokes about him. But the real life of the red commander was no less interesting. He loved cars, argued with the teachers of the military academy. And Chapaev is not a real surname.

Hard childhood

Vasily Ivanovich was born into a poor peasant family. The only wealth of his parents is nine eternally hungry children, of which the future hero of the Civil War was the sixth.

As the legend says, he was born prematurely and kept warm in his father's fur mitten on the stove. His parents assigned him to the seminary in the hope that he would become a priest. But when once guilty Vasya was put in a wooden punishment cell in a severe frost in one shirt, he escaped. He tried to be a merchant, but he couldn’t - the main trading commandment disgusted him too much: “If you don’t deceive, you won’t sell, if you don’t cheat, you won’t profit.” “My childhood was dark and difficult. I had to humiliate myself and starve a lot. From an early age, he ran around strangers, ”the divisional commander later recalled.

"Chapaev"

It is believed that the family of Vasily Ivanovich bore the name of Gavrilov. "Chapaev" or "Chepai" was the nickname that the grandfather of the divisional commander, Stepan Gavrilovich, received. Either in 1882, or in 1883, they loaded logs with their comrades, and Stepan, as the elder, constantly commanded - “Chop, scoop!”, Which meant: “take it, take it”. So it stuck to him - Chepai, and the nickname later turned into a surname.

They say that the original "Chepai" became "Chapaev" with light hand Dmitry Furmanov, the author of the famous novel, who decided that “it sounds better this way.” But in the surviving documents from the time of the civil war, Vasily appears under both options.

Perhaps the name "Chapaev" appeared as a result of a typo.

Academy student

Chapaev's education, contrary to popular belief, was not limited to two years of parochial school. In 1918 he was enrolled in military academy The Red Army, where many fighters were "driven" to improve their general literacy and strategy training. According to the memoirs of his classmate, the peaceful student life weighed heavily on Chapaev: “Damn it! I'm leaving! To come up with such nonsense - fighting people at a desk! Two months later, he filed a report with a request to release him from this "prison" to the front.

Several stories have been preserved about Vasily Ivanovich's stay at the academy. The first says that in a geography exam, in response to a question from an old general about the significance of the Neman River, Chapaev asked the professor if he knew about the significance of the Solyanka River, where he fought with the Cossacks. According to the second, in a discussion of the battle of Cannae, he called the Romans "blind kittens", telling the teacher, a prominent military theorist Sechenov: "We have already shown generals like you how to fight!"

Motorist

We all imagine Chapaev as a courageous fighter with a fluffy mustache, a naked saber and galloping on a dashing horse. This image was created by the national actor Boris Babochkin. In life, Vasily Ivanovich preferred cars to horses.

Even on the fronts of the First World War, he received a serious wound in the thigh, so riding became a problem. So Chapaev became one of the first red commanders who moved to the car.

He chose iron horses very meticulously. The first - the American "Stever", he rejected due to strong shaking, the red "Packard", which replaced him, also had to be abandoned - he was not suitable for military operations in the steppe. But the "Ford", which squeezed 70 miles off-road, the red commander liked. Chapaev also selected the best drivers. One of them, Nikolai Ivanov, was practically taken to Moscow by force and put as the personal driver of Lenin's sister, Anna Ulyanova-Elizarova.

Women's deceit

The famous commander Chapaev was the eternal loser on the personal front. His first wife, the petty-bourgeois Pelageya Metlina, whom Chapaev's parents disapproved of, calling her "the city white-handed woman", gave birth to three children for him, but she did not wait for her husband from the front - she went to a neighbor. Vasily Ivanovich was very upset by her act - he loved his wife. Chapaev often repeated to his daughter Claudia: “Oh, you are beautiful. Looks like a mother."

The second companion of Chapaev, however, already a civilian, was also called Pelageya. She was the widow of Vasily's comrade-in-arms, Pyotr Kamishkertsev, to whom the division commander promised to take care of his family. At first he sent her benefits, then they decided to move in together. But history repeated itself - during the absence of her husband, Pelageya had an affair with a certain Georgy Zhivolozhinov. Once Chapaev found them together and almost sent the unfortunate lover to the next world.

When the passions subsided, Kamishkertseva decided to go to the world, took the children and went to her husband's headquarters. The children were allowed to visit their father, but she was not. They say that after that she took revenge on Chapaev, giving the Whites the location of the Red Army troops and data on their numbers.

fatal water

The death of Vasily Ivanovich is shrouded in mystery. On September 4, 1919, Borodin's detachments approached the city of Lbischensk, where the headquarters of Chapaev's division was located with a small number of fighters. During the defense, Chapaev was severely wounded in the stomach, his soldiers put the commander on a raft and ferried across the Urals, but he died from blood loss. The body was buried in the coastal sand, and the traces were hidden so that the Cossacks would not find it. Searching for the grave subsequently became useless, as the river changed its course. This story was confirmed by a participant in the events. According to another version, being wounded in the arm, Chapaev drowned, unable to cope with the current.

“Maybe he floated out?”

Neither the body nor the grave of Chapaev could be found. This gave rise to a completely logical version of the surviving hero. Someone said that due to a severe wound, he lost his memory and lived somewhere under a different name.

Some claimed that he was safely transported to the other side, from where he went to Frunze, to be responsible for the surrendered city. In Samara, he was put under arrest, and then they decided to officially “kill the hero”, ending his military career with a beautiful end.

This story was told by a certain Onyanov from the Tomsk region, who allegedly met his aged commander many years later. The story looks doubtful, because in the difficult conditions of the civil war it was inappropriate to “scatter” experienced military leaders, who were highly respected by the soldiers.

Most likely, this is a myth generated by the hope that the hero was saved.

Each era gives birth to its heroes. The 20th century in the history of our country is a lot of social upheavals - several revolutions and wars. One of them was a civil war, in which different worldviews of different social strata clashed. Among the heroes who defended the interests of the young Soviet Republic, there is a truly unique personality - this is Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev.

By today's standards, he was a young man, because at the time of his death he was only 32 years old. Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev was born on January 28, 1887 in the Chuvash village of Budaika, which was located in the Cheboksary district of the Kazan province. In the Russian family of the peasant Ivan Chapaev, he was the sixth child. He was born prematurely and was very weak. Therefore, the parents could hardly imagine what a heroic fate awaits their tiny Vasenka.

A large family was very poor and in search of a better life and earnings, she moved to relatives in the Samara province and settled in the village of Balakovo. Here Vasily went to a parochial school in the expectation that he could become a priest. But this did not happen. But he married the young daughter of the priest Pelageya Metlina. Soon he was drafted into the army. After serving for a year, Vasily Chapaev was discharged for health reasons.

Returning to his family, he began to work as a carpenter, until it struck in 1914. By this time, the family of Vasily and Pelageya already had three children. In January, Vasily Chapaev goes to the front and proves himself to be a skillful and brave warrior. For courage and courage he is awarded three St. George's crosses and the St. George medal. The first world sergeant major Vasily Chapaev finished with the full St. George's Cavalier.

In the autumn of 1917, he chose the side of the Bolsheviks and proved to be an excellent organizer. In the Saratov province, he creates 14 detachments of the Red Guard, which take part in the battles against General Kaledin. In May 1918, the Pugachev brigade was formed from these detachments, and Chapaev was appointed to command it. This brigade, led by a self-taught commander, recaptures the city of Nikolaevsk from the Czechoslovaks.

The popularity and fame of the young red commander grew literally before our eyes, while Chapaev barely knew how to read and was completely unable, or did not want to, obey orders. The actions of the 2nd Nikolaev division, led by Chapaev, instilled fear in the enemies, but often gave away partisanism. Therefore, the command decided to send him to study at the newly opened Academy of the General Staff of the Red Army. But the young commander could not sit at the training table for a long time and returned to the front.

In the summer of 1919, under his command, the 25th Infantry Division carried out successful operations against the White Guards of Kolchak. In early June, the Chapaev division liberates Ufa, and a month later the city of Uralsk. The professional military men who led the White Guard troops paid tribute to the military talents of the young Red Guard commander. A real military nugget was seen in him not only by his comrades-in-arms, but also by opponents.

An early death prevented Chapaev from revealing the true talent of the commander, which was caused by a tragedy caused by a military mistake, the only one in the military career of Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev. This happened on September 5, 1919. Chapaev's division advanced and broke away from the main forces. Having stopped for a night's rest, the divisional headquarters was located separately from the parts of the division. The White Guards under the command of General Borodin, numbering up to 2000 bayonets, attacked the headquarters of the Chapaevsky division.

Wounded in the head and stomach, the division commander was able to organize the Red Guards retreating in disorder for defense. But completely disproportionate forces forced them to retreat. The soldiers transported the wounded commander across the Ural River on a raft, but he died of his wounds. They buried Chapaev in the coastal sand so that the enemies would not desecrate his body. Subsequently, the burial place could not be found.

Even after the death of the commander, the Chapaev division continued to successfully crush the enemies. For many, it will be a discovery that the subsequently famous Czech writer Yaroslav Gashek, the famous partisan commander Sidor Kovpak, Major General Ivan Panfilov, whose fighters glorified themselves during the defense, fought in the ranks of the Chapaevsky division.

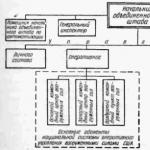

As often happens, in the history of the Civil War in Russia, to this day, true and tragic facts have been tightly mixed with myths, speculation, rumors, epics, and, of course, with anecdotes. Especially a lot of them are associated with the legendary red commander. Almost everything that we have known about this hero since childhood is mainly connected with two sources - with the film "Chapaev" (directed by Georgy and Sergey Vasiliev) and with the story "Chapaev" (by Dmitry Furmanov). However, at the same time, we forget that both the book and the film are works of art, which contains both the author's fiction and direct historical inaccuracies (Fig. 1).

The beginning of the way

He was born on January 28 (February 9, according to the new style), 1887, into a Russian peasant family in the village of Budaika, Cheboksary district, Kazan province (now the territory of the Leninsky district of the city of Cheboksary). Vasily was the sixth child in the family of Ivan Stepanovich Chapaev (1854-1921) (Fig. 2).

Soon after the birth of Vasily, the Chapaev family moved to the village of Balakovo, Nikolaev district, Samara province (now the city of Balakovo, Saratov region). Ivan Stepanovich assigned his son to the local parochial school, whose patron was his wealthy cousin. Before that, there were already priests in the Chapaev family, and the parents wanted Vasily to become a clergyman, but life decreed otherwise.

In the autumn of 1908, Vasily was drafted into the army and sent to Kyiv. But already in the spring next year due to illness, Chapaev was dismissed from the army to the reserve and transferred to the first-class militia warriors. After that, until the start of the First World War, he did not serve in the regular army, but worked as a carpenter. From 1912 to 1914 V.I. Chapaev and his family lived in the city of Melekess (now Dimitrovgrad, Ulyanovsk Region). Here his son Arkady was born.

With the outbreak of war, Chapaev was called up for military service on September 20, 1914 and sent to the 159th reserve infantry regiment in the city of Atkarsk. He went to the front in January 1915. The future red commander fought in the 326th Belgorai Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Infantry Division in the 9th Army of the Southwestern Front in Volyn and Galicia, where he was wounded. In July 1915, he completed training courses and received the rank of junior non-commissioned officer, and in October - senior. War V.I. Chapaev graduated with the rank of sergeant major, and for his courage he was awarded the St. George medal and the soldiers' St. George's crosses of three degrees (Fig. 3.4).

He met the February Revolution in a hospital in Saratov, and here, on September 28, 1917, he joined the ranks of the RSDLP (b). Soon he was elected commander of the 138th infantry reserve regiment stationed in Nikolaevsk, and on December 18, by the county congress of Soviets, he was appointed military commissar of the Nikolaevsky district. In this position, V.I. Chapaev led the dispersal of the Nikolaev district zemstvo, and then organized the district Red Guard, which consisted of 14 detachments (Fig. 5).

On the initiative of V.I. Chapaev on May 25, 1918, it was decided to reorganize the Red Guard detachments into two regiments of the Red Army, which received the names "named after Stepan Razin" and "named after Yemelyan Pugachev." Under the command of V.I. Chapaev, both regiments merged into the Pugachev brigade, which, a few days after its creation, took part in battles with the Czechoslovaks and the Komuch People's Army. The biggest victory of this brigade was the battle for the city of Nikolaevsk, which ended in the complete defeat of the Komuchevites and Czechoslovaks.

Battle for Nikolaevsk

As you know, Samara was captured by units of the Czechoslovak Corps on June 8, 1918, after which the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly (Komuch for short) came to power in the city. Then, during almost the entire summer of 1918, the retreat of the Red Army units continued in the east of the country. Only towards the end of this summer did Lenin's government manage to stop the joint offensive of the Czechoslovaks and the Whites in the Middle Volga region.

In early August, after extensive mobilization, the I, II, III and IV armies were formed as part of the Eastern Front, and at the end of the month - the V army and the Turkestan army. In the direction of Kazan and Simbirsk, from mid-August, the 1st Army under the command of Mikhail Tukhachevsky began to operate, to which an armored train was handed over (Fig. 6).

At this time, a grouping consisting of parts of the Komuch People's Army and Czechoslovak troops under the command of Captain Chechek launched a counteroffensive on the southern sector of the Eastern Front of the Reds. The red regiments, unable to withstand their sudden onslaught, left Nikolaevsk in the middle of the day on August 20. It was not even a retreat, but a stampede, because of which the workers of Soviet institutions did not even have time to leave the city. As a result, according to eyewitnesses, the White Guards who broke into Nikolaevsk immediately began general searches and executions of communists and Soviet employees.

The closest associate V.I. recalled further events near Nikolaevsk. Chapaeva Ivan Semyonovich Kutyakov (Fig. 7).

“At this time, in the village of Porubezhka, where the 1st Pugachevsky regiment was located, Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev arrived in a troika with a group of orderlies ... He arrived in his brigade, excited by recent failures.

The news of Chapaev's arrival quickly spread through the red chains. Not only commanders and fighters, but also peasants began to flock to the headquarters of the 1st Pugachev Regiment. They wanted to see Chapai with their own eyes, whose fame spread throughout the Trans-Volga steppe, to all villages, villages and farms.

Chapaev accepted the report of the commander of the 1st Pugachev Regiment. Tov. Plyasunkov reported to Vasily Ivanovich that his regiment was fighting for the second day with a detachment of White Czechs, who at dawn had captured the crossing across the Bolshoy Irgiz River near the village of Porubezhka, and now they were persistently striving to occupy Porubezhka ...

Chapaev immediately outlined a bold plan, which, if successful, promised to lead not only to the liberation of Nikolaevsk, but also to the complete defeat of the enemy. According to Chapaev's plan, the regiments were to move on to energetic actions. 1st Pugachevsky received an order: not to retreat from Porubezhka, but to counterattack the White Czechs and seize back the crossing across the Bolshoy Irgiz River. And after stepan Razin's regiment went to the rear of the White Czechs, together with him, attack the enemy in the village of Tavolzhanka.

Meanwhile, Stepan Razin's regiment was already on its way to Davydovka. The messenger sent by Chapaev found the regiment at rest in the village of Rakhmanovka. Here the commander of the regiment Kutyakov received Chapaev's order ... Since there is no ford across the river, and the right bank dominates the left, it is hardly possible to attack the White Czechs with a frontal strike. Therefore, the commander of the 2nd Stepan Razin regiment was asked to immediately move through the village of Gusikha to the rear of the White Czechs in order to simultaneously attack the enemy from the north in the area of the village of Tavolzhanka occupied by him and then advance on Nikolaevsk.

Chapaev's decision was extremely bold. To many, who were under the influence of the victories of the White Czechs, it seemed impossible. But Chapaev's will to win, his great confidence in success, and boundless hatred of the enemies of the workers and peasants kindled all the fighters and commanders with fighting enthusiasm. The regiments unanimously began to carry out the order.

On August 21, the Pugachev regiment under the leadership of Vasily Ivanovich made a brilliant demonstration, pulling the fire and attention of the enemy onto itself. Thanks to this, the Razintsy successfully completed their march maneuver and went from the north to the rear of the village of Tavolzhanki, at a distance of two kilometers from the heavy enemy battery firing at the Pugachev regiment. The commander of the 2nd Stepan Razin regiment decided to take advantage of the opportunity and ordered the battery commander Comrade Rapetsky to open fire on the enemy. The battery of the Razints moved forward at full gallop, took off from the limbers and, with a direct fire, showered the Czech guns with buckshot with the first volley. Immediately, without a moment's delay, the cavalry squadron and three battalions of the Razints, with a cry of "Hurrah," rushed to the attack.

Sudden shelling and the appearance of the Reds in the rear caused confusion in the ranks of the enemy. The enemy gunners abandoned their guns and ran in panic to the cover units. The cover did not have time to prepare for battle, and was destroyed along with the gunners.

Chapaev, who personally led the Pugachev regiment in this battle, launched a frontal attack on enemy forces. As a result, not a single enemy soldier escaped.

By evening, when the crimson rays of the setting sun illuminated the battlefield, covered with the corpses of the White Czech soldiers, the regiments occupied Tavolzhanka. In this battle, 60 machine guns, 4 heavy guns and many other military booty were captured.

Despite the strong fatigue of the fighters, Chapaev ordered to continue moving forward to Nikolaevsk. At about one in the morning, the regiments reached the village of Puzanikha, a few kilometers from Nikolaevsk. Here in view total darkness had to linger. The soldiers were ordered not to leave the ranks. The battalions left the road and stood up. The fighters struggled with drowsiness. There is deep silence all around. At this time, unexpectedly, from the rear, some convoy drove up close to the chains. The front carts were detained only fifty meters from the location of the artillery. They were approached by the commander of the 2nd Battalion of the Stepan Razin Regiment Comrade Bubenets. To his question, one of those riding in the front wagon explained in broken Russian that he was a Czechoslovak colonel and was heading with the regiment to Nikolaevsk. Tov. Bubenets stood at the front, put his hand to the visor and said that he would immediately report the arrival of the "allies" to his colonel - the commander of the volunteer detachment.

Tov. Bubenets, a former guards officer, from the beginning of the Great October Revolution went over to the side of the Soviet government and devotedly served the cause of the proletariat. Together with him, his two brothers also voluntarily joined the ranks of the Red Guard. They were taken prisoner by the founders and brutally killed. Bubenets was one of the most combative, courageous, enterprising and decisive commanders. Chapaev, who had a sharp hatred for the officers, trusted him in everything.

The message of Comrade Bubenets raised the entire regiment to its feet. At first, no one could believe this meeting. But in the darkness on the road where the enemy column was standing, cigarette lights could be seen and the bewildered voices of enemy fighters were heard, trying to find an explanation for the unexpected stop. There could be no doubt. Twenty minutes later, two battalions were brought close to the enemy. On a signal, they opened fire in volleys. Frightened voices of white Czechs were heard. Everything is mixed...

By dawn the battle was over. In the morning twilight, the battlefield was outlined, stretching along the road; it was covered with the corpses of white Czechs, carters and horses. The 40 machine guns taken in this battle, together with those captured in the daytime battle, served as the main reserve for the Chapaev units until the end of the civil war.

The destruction of the enemy regiment, captured on the way, completed the defeat of the enemy. The White Czechs, who occupied Nikolaevsk, left the city that same night and retreated in panic through Seleznikha to Bogorodskoye. At about eight o'clock in the morning on August 22, Chapaev's brigade occupied Nikolaevsk with a small fight, renamed Pugachev at Chapaev's suggestion" (Fig. 8-10).

"The Red Army is the strongest of all"

Samarans regularly remember this red divisional commander, primarily because since November 1932 in our city there has been a well-known monument to Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev by the sculptor Matvey Manizer, which, along with a few other sights, has long become a symbol of Samara.

In particular, one can still hear the opinion that on October 7, 1918, Samara was liberated from the Czechoslovak units, among others, by the Chapaev-led military unit- The 25th Nikolaev division, which at that time was part of the IV Army. At the same time, allegedly, Vasily Ivanovich himself, just like in the legends and anecdotes folded about him among the people, was the first to burst into the city on a dashing horse, hacking the White Guards and Czechs left and right with a saber. And if such stories still take place, then they are inspired, of course, by the presence of a monument to Chapaev in Samara (Fig. 11).

Meanwhile, the events near Samara in the second half of 1918 were not at all the way we heard in the legends. On September 10, as a result of successful military operations, the Red Army drove the Komuchevites out of Kazan, and on September 12 - from Simbirsk. But on August 30, 1918, an attempt was made on the life of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, at the Michelson plant in Moscow, who was wounded by two pistol bullets. Therefore, shortly after Simbirsk was liberated from the Czechoslovaks, on behalf of the command of the Eastern Front, a telegram flew to the Council of People's Commissars with the following content: "Moscow Kremlin to Lenin For your first bullet, the Red Army will take Simbirsk for the second will be Samara."

In pursuance of these plans, after the successful completion of the Simbirsk operation, the commander of the Eastern Front, Joachim Vatsetis, on September 20 ordered a broad offensive against Syzran and Samara. The Red troops approached Syzran on September 28-29, and, despite the fierce resistance of the besieged, over the next five days they managed to destroy all the main nodes of the Czech defense one after another. So, by 12 o'clock on October 3, 1918, the territory of the city was completely cleared of the Komuchevites and Czechoslovaks, mainly by the forces of the Iron Division under the leadership of Hayk Guy (Fig. 12).  The remnants of the Czechoslovak units retreated to the railway bridge, and after the last Czech soldier crossed it to the left bank on the night of October 4, two spans of this grandiose structure were blown up by Czechoslovak sappers. Railway communication between Syzran and Samara was interrupted for a long time (Fig. 13-15).

The remnants of the Czechoslovak units retreated to the railway bridge, and after the last Czech soldier crossed it to the left bank on the night of October 4, two spans of this grandiose structure were blown up by Czechoslovak sappers. Railway communication between Syzran and Samara was interrupted for a long time (Fig. 13-15).

On the morning of October 7, 1918, from the south, from the Lipyagi station, the advanced units of the 1st Samara Division, which was part of the IV Army, approached the Zasamarskaya Sloboda, which captured this suburb practically without a fight. During their retreat, the Czechs set fire to the pontoon bridge that existed at that time across the Samara River, preventing the city fire brigade from extinguishing it. And after a red armored train headed from the side of the Kryazh station towards Samara, Czech miners blew up the span of the railway bridge across the Samara River as it approached. This happened about two o'clock in the afternoon on October 7, 1918.

Only after the working detachments from the Samara factories arrived in time for the burning pontoon bridge, the Czech units guarding the bridge in a panic left their positions on the river bank and retreated to the station. The last echelon with the invaders and their henchmen left our city to the east at about 5 pm. And three hours later, the 24th Iron Division under the command of Guy entered Samara from the north side. Parts of the 1st army of Tukhachevsky broke into our city a few hours later along the extinguished pontoon bridge.

And what about the legendary Chapaev cavalry? As evidenced historical documents, in early October 1918, the Nikolaev division under the command of Chapaev was located about 200 kilometers south of Samara, in the Uralsk region. But, despite such a distance from our city, the unit of the legendary red commander still played a very significant role in the Samara military operation. It turns out that in those days when the IV Army launched an offensive against Samara, Divisional Commander Chapaev received an order: to divert the main forces of the Ural Cossacks to himself so that they could not hit the rear and flank of the Red troops.

Here is what I.S. writes about this in his memoirs. Kutyakov: “... Chapaev was ordered not only to defend himself with his two regiments, but to advance on Uralsk. This task, of course, was unbearable for a weak division, but Vasily Ivanovich, implicitly following the orders of the army headquarters, resolutely moved east ... His energetic actions forced the White command to throw almost the entire White Cossack army against the Nikolaev division ... The main forces of the 4th Army, moving to Samara, were left in complete peace. During the entire operation, the Cossacks never attacked not only the flank, but also the rear of the 4th Army, which allowed the Red Army units to occupy Samara on October 7, 1918. In a word, it must be recognized that the monument to V.I. Chapaev in Samara deservedly established.

In late 1918 and early 1919, V.I. Chapaev visited Samara several times at the headquarters of the army, which at that time was already commanded by Mikhail Frunze. In particular, after a three-month study at the Academy of the General Staff in early February 1919, Chapaev, who was extremely tired of what he considered to be aimless studies, managed to obtain permission to depart back to the Eastern Front, to his 4th Army, which at that time commanded Mikhail Vasilievich Frunze. In mid-February 1919, Chapaev arrived in Samara, at the headquarters of this army (Fig. 16, 17).

M.V. Frunze at that time had just returned from the Ural front. During this time, he heard a lot about the exploits of Chapaev, his decisiveness and heroism from the soldiers of the Chapaev regiments, who had just taken the city of Uralsk, the political center of the Cossacks, and fought bloody battles for the possession of the city of Lbischensky. Frunze paid great attention to the creation of combat-ready units and the selection of talented, experienced commanders, and therefore he immediately appointed V.I. Chapaev as the commander of the Alexander-Gai brigade, and Dmitry Andreyevich Furmanov, who later became the author of a well-known book about the legendary commander, was his commissar. Orderly at V.I. Chapaev at that time was Pyotr Semyonovich Isaev, who became especially famous after the release of the film Chapaev in 1934 (Fig. 18, 19).

This brigade, formed mainly from the peasants of the Volga region, stood in the Alexandrov Gai area. Prior to the appointment of Vasily Ivanovich, it was commanded by an “old-mode” colonel, who was very cautious, and therefore his unit acted indecisively and unsuccessfully, was mainly on the defensive, and suffered one defeat after another from raids and raids by white Cossack detachments.

Mikhail Vasilyevich Frunze set Chapaev the task of capturing the area of the village of Slomikhinskaya, and then continuing the offensive against Lbischensk in order to threaten the enemy's main forces from the rear. Having received this task, Chapaev decided to call on Uralsk in order to personally agree on its implementation.

Chapaev's arrival came as a complete surprise to his comrades-in-arms. Within a few hours, all of Chapaev's former associates gathered. Some came straight from the battlefield to see their favorite commander. And Chapaev, upon arrival at the brigade, visited all the regiments and battalions in a few days, got acquainted with the command staff, held a series of meetings, paid a lot of attention to the food supply of the units and replenishing them with weapons and ammunition.

As for Furmanov, Chapaev at first treated him with caution. He had not yet outlived the prejudice against political workers who had come to the front for the first time, which was then characteristic of many Red commanders who had come out of the people. However, soon the division commander changed his attitude towards Furmanov. He was convinced of his education and decency, for a long time he had conversations with him not only on general topics, but also on history, literature, geography and other subjects that seemed to have nothing to do with military affairs. Having learned from Furmanov a lot of things that he had never heard of before, Chapaev eventually gained confidence and respect for him, and more than once consulted with his political officer on issues of interest to him.

Conducted by V.I. Chapaev, the preparation of the Alexander-Gai brigade eventually led the unit to combat success. In the first battle on March 16, 1919, the brigade with one blow knocked out the White Guards from the village of Slomikhinskaya, where the headquarters of Colonel Borodin was located, and threw their remnants far into the Ural steppes. In the future, the Ural Cossack army also suffered defeat from the Alexander-Gai brigade, also near Uralsk and Lbischensk, which was occupied by the 1st brigade of I.S. Kutyakova.

The death of Chapaev

In June 1919, the Pugachev brigade was renamed the 25th Infantry Division under the command of V.I. Chapaeva, and she participated in the Bugulma and Belebeev operations against Kolchak's army. Under the leadership of Chapaev, this division occupied Ufa on June 9, 1919, and Uralsk on July 11. During the capture of Ufa, Chapaev was wounded in the head by a burst from an aircraft machine gun (Fig. 20).

In early September 1919, units of the 25th Red Division under the command of Chapaev were on vacation near the small town of Lbischensk (now Chapaevo) on the Ural River. On the morning of September 4, the divisional commander, together with the military commissar Baturin, left for the village of Sakharnaya, where one of his units was stationed. But he did not know that at the same time, along the valley of the small river Kushum, a tributary of the Urals, in the direction of Lbischensk, the 2nd Cavalry Cossack Corps under the command of General Sladkov, consisting of two cavalry divisions, was moving freely. In total, there were about 5 thousand sabers in the corps. By the evening of the same day, the Cossacks reached a small tract, located only 25 kilometers from the city, where they took refuge in thick reeds. Here they began to wait for darkness in order to attack the headquarters of the 25th Red Division under the cover of night, which at that moment was guarded by soldiers of a training unit numbering only 600 bayonets.

The aviation reconnaissance unit (four aircraft), flying in the vicinity of Lbischensk on the afternoon of September 4, did not detect this huge Cossack formation in the immediate vicinity of the location of the Chapaev headquarters. At the same time, experts believe that the pilots could not simply physically not see 5,000 horsemen from the air, even if they were disguised in the reeds. Historians explain such “blindness” as a direct betrayal on the part of the pilots, especially since the very next day they flew on their planes to the side of the Cossacks, where the entire squadron surrendered to the headquarters of General Sladkov (Fig. 21, 22).

One way or another, but no one could report to Chapaev, who returned to his headquarters late in the evening, about the danger threatening him. On the outskirts of the town, only ordinary guard posts were set up, and the entire red headquarters and the training unit guarding it fell asleep peacefully. No one heard how, under the cover of darkness, the Cossacks silently removed the guards, and at about one in the morning the corps of General Sladkov hit Lbischensk with all its might. By dawn on September 5, the city was already entirely in the hands of the Cossacks. Chapaev himself, together with a handful of fighters and orderly Peter Isaev, was able to break through to the banks of the Ural River and even swim to the opposite bank, but in the middle of the river he was hit by an enemy bullet. Historians believe that the last minutes of the life of the legendary Red Divisional Commander are shown with documentary accuracy in the famous film "Chapaev", filmed in 1934 by directors Vasilievs.

On the morning of September 5, a message about the defeat of the headquarters of the 25th division was received by I.S. Kutyakov, commander of a group of red units, which included 8 rifle and 2 cavalry regiments, as well as divisional artillery. This group was stationed 15 kilometers from Lbischensk. A few hours later, the red units entered into battle with the Cossacks, and by the evening of the same day they were driven out of the city. By order of Kutyakov, a special group was formed to search for Chapaev's body in the Ural River, but even after several days of inspection of the river valley, it was never found (Fig. 23).

Anecdote on the topic

An aircraft was sent to Chapaev's division. Vasily Ivanovich wished to personally look at the outlandish car. He walked around him, looked into the cockpit, twirled his mustache, and then said to Petka:

No, we do not need such an airplane.

Why? Petka asks.

The saddle is inconveniently located, Chapaev explains. - Well, how can you chop with a saber? If you cut it, you will touch the wings, and they will fall off ... (Fig. 24-30).

Valery EROFEEV.

Bibliography

Banikin V. Stories about Chapaev. Kuibyshev: Kuibyshev book publishing house, 1954. 109 p.

Belyakov A.V. Flying through the years M.: Military Publishing House, 1988. 335 p.

Borgens V. Chapaev. Kuibyshev, Kuib. region publishing house 1939. 80 p.

Vladimirov V.V. . Where V.I. lived and fought. Chapaev. Travel notes. - Cheboksary. 1997. 82 p.

Kononov A. Stories about Chapaev. M.: Children's literature, 1965. 62 p.

Kutyakov I.S. The battle path of Chapaev. Kuibyshev, Kuib. book. publishing house 1969. 96 p.

Legendary chief. Book about V.I. Chapaev. Collection. Editor-compiler N.V. Sorokin. Kuibyshev, Kuib. book. publishing house 1974. 368 p.

On the battle path of Chapaev. Brief guide. Kuibyshev: Ed. gas. "Red Army", 1936.

Timin T. Chapaev - real and imaginary. M., "Veteran of the Motherland". 1997. 120 p., illustration.

Furmanov D.A. Chapaev. Editions of different years.

Khlebnikov N.M., Evlampiev P.S., Volodikhin Ya.A. Legendary Chapaevskaya. Moscow: Knowledge, 1975. 429 p.

Chapaeva E. My unknown Chapaev. M.: "Corvette", 2005. 478 p.

Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev (signed as Chepaev). Born on January 28 (February 9), 1887 in the village of Budaika, Cheboksary district, Kazan province - died on September 5, 1919 near Lbischensk, Ural region. The legendary commander of the Red Army, a participant in the First World War and the Civil War.

Vasily Chapaev was born on January 28 (February 9), 1887 in the village of Budaika, Cheboksary district, Kazan province, into a peasant family. The ancestors of the Chapaevs have lived there since ancient times. Budaika, like some other neighboring Russian villages, arose near the city of Cheboksary, founded on the instructions of the king in 1555 on the site of an ancient Chuvash settlement.

Father - Ivan Stepanovich, by nationality - Erzya. Belonged to the poorest Buda peasants.

Mother Ekaterina Semyonovna is of Russian-Chuvash origin.

Later brother Chapaeva - Mikhail Ivanovich - spoke about the origin of their surname as follows: "Vasily Ivanovich's grandfather, Stepan Gavrilovich, was written in documents by Gavrilov. In 1882 or 1883, Stepan Gavrilovich and his comrades contracted to load logs. The tramp Venyaminov asked them to join the artel. work: - Chap, scoop! (Catch, cling, which means "take it, take it").

When the work was completed, the contractor did not immediately give money for the work. The money was to be received and distributed as senior Stepan Gavrilovich. The old man went for money for a long time. Veniaminov ran along the pier, looking for Stepan. Forgetting his name, he asked everyone:

- Have you seen Gryazevsky (Gryazevo is another name for the village of Budaika) an old man, handsome, curly-haired, everything says “chapai”?

- He, Chapai, will not give you money, - they made fun of Venyaminov. Then, when the grandfather received the money he had earned, he found Venyaminov, gave him his earnings, treated him.

And the nickname "Chapai" remained with Stepan. The nickname “Chapaevs” was assigned to the descendants, which then became the official surname..

Some time later, in search of a better life, the Chapaev family moved to the village of Balakovo, Nikolaevsky district, Samara province. Ivan Stepanovich assigned his son to the local parochial school, whose patron was his wealthy cousin. There were already priests in the Chapaev family, and the parents wanted Vasily to become a clergyman, but life decreed otherwise.

In the autumn of 1908, Vasily was drafted into the army and sent to Kyiv. But already in the spring of next year, for unknown reasons, Chapaev was dismissed from the army to the reserve and transferred to the first-class militia warriors. According to the official version, due to illness. The version about his political unreliability, because of which he was transferred to the warriors, is not confirmed by anything.

Before the World War, he did not serve in the regular army. He worked as a carpenter.

From 1912 to 1914, Chapaev and his family lived in the city of Melekess (now Dimitrovgrad, Ulyanovsk Region). With the outbreak of war, on September 20, 1914, Chapaev was called up for military service and sent to the 159th reserve infantry regiment in the city of Atkarsk.

Chapaev went to the front in January 1915. He fought in the 326th Belgorai Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Infantry Division in the 9th Army of the Southwestern Front in Volyn and Galicia. Was injured. In July 1915 he graduated from the training team, received the rank of junior non-commissioned officer, and in October - senior. He ended the war with the rank of sergeant major. For his bravery, he was awarded the St. George medal and the soldiers' St. George's crosses of three degrees.

I met the February Revolution in a hospital in Saratov. September 28, 1917 joined the RSDLP (b). He was elected commander of the 138th Infantry Reserve Regiment stationed in Nikolaevsk. On December 18, the district congress of Soviets elected the military commissar of the Nikolaevsky district. In this position, he led the dispersal of the Nikolaev district zemstvo. Organized the county Red Guard of 14 detachments.

Participated in the campaign against General Kaledin (near Tsaritsyn), then (in the spring of 1918) in the campaign of the Special Army against Uralsk. On his initiative, on May 25, a decision was made to reorganize the Red Guard detachments into two regiments of the Red Army: them. Stepan Razin and them. Pugachev, united in the Pugachev brigade under the command of Chapaev.

Later he participated in battles with the Czechoslovaks and the People's Army, from whom Nikolaevsk was recaptured, renamed Pugachev in honor of the brigade.

From November 1918 to February 1919 - at the Academy of the General Staff. Then - the commissioner of internal affairs of the Nikolaevsky district.

Since May 1919 - brigade commander of the Special Alexander-Gai Brigade, since June - head of the 25th Infantry Division, which participated in the Bugulma and Belebeev operations against Kolchak's army.

During the capture of Ufa, Chapaev was wounded in the head by a burst from an aircraft machine gun.

The appearance of Vasily Chapaev

The chief of staff of the 4th Army, Fyodor Novitsky, described Chapaev as follows: “A man of about thirty, of medium height, thin, clean-shaven and with a neat haircut, entered the office slowly and very respectfully. Chapaev was dressed not only neatly, but also exquisitely: a superbly tailored overcoat made of good material, a gray lambskin cap with a gold braid on top, smart reindeer cloak boots with fur outside. He wore a Caucasian-style saber, richly trimmed with silver, and a Mauser pistol neatly fitted to the side.

The death of Vasily Chapaev

Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev died on September 5, 1919 as a result of a deep raid by the Cossack detachment of Colonel N.N. -Kazakhstan region of Kazakhstan), where the headquarters of the 25th division was located.

Chapaev's division, which broke away from the rear and suffered heavy losses, settled down in early September to rest in the Lbishensk region, and in Lbishensk itself the division headquarters, supply department, tribunal, revolutionary committee and other divisional institutions were located total strength nearly two thousand people. In addition, in the city there were about two thousand mobilized peasant wagon trains who did not have any weapons.

The protection of the city was carried out by a divisional school in the amount of 600 people - it was these 600 active bayonets that were Chapaev's main force at the time of the attack. The main forces of the division were at a distance of 40-70 km from the city.

The command of the Ural army decided to undertake a raid on Lbischensk. On the evening of August 31, a select detachment under the command of Colonel Borodin left the village of Kalyonny.

On September 4, Borodin's detachment secretly approached the city and hid in the reeds in the backwaters of the Urals. Aerial reconnaissance (4 airplanes) did not report this to Chapaev, apparently due to the fact that the pilots sympathized with the Whites (after Chapaev's death, they all flew over to the side of the Whites).

At dawn on September 5, the Cossacks attacked Lbischensk. Panic and chaos began, part of the Red Army crowded on Cathedral Square, was surrounded and captured there. Others were taken prisoner or killed while clearing the city. Only a small part managed to break through to the Ural River. All prisoners were executed - they were shot in batches of 100-200 people on the banks of the Urals. Among those captured after the battle and shot was the divisional commissar P.S. Baturin, who tried to hide in the furnace of one of the houses. The chief of staff of the Ural White Army, Colonel Motornov, described the results of this operation as follows: "Lbischensk was taken on September 5 with a stubborn battle that lasted 6 hours. As a result, the headquarters of the 25th division, the instructor school, divisional institutions were destroyed and captured. Four airplanes, five cars and other military booty were captured".

According to the documents, to capture Chapaev, Borodin allocated a special platoon under the command of the lieutenant Belonozhkin, who, led by a captured Red Army soldier, attacked the house where Chapaev lodged, but missed him: the Cossacks attacked the Red Army soldier who appeared from the house, mistaking him for Chapaev himself, in while Chapaev jumped out the window and managed to escape. During the flight, he was wounded in the arm by Belonozhkin's shot.

Having gathered and organized the Red Army soldiers, who fled to the river in a panic, Chapaev organized a detachment of about a hundred people with a machine gun and was able to throw back Belonozhkin, who did not have machine guns. However, he was wounded in the stomach while doing so. According to the story of Chapaev's eldest son, Alexander, two Hungarian Red Army soldiers put the wounded Chapaev on a raft made from half a gate and ferried him across the Urals. But on the other side it turned out that Chapaev died from blood loss. The Hungarians buried his body with their hands in the coastal sand and threw reeds so that the Cossacks would not find the grave.

This story was subsequently confirmed by one of the participants in the events, who in 1962 sent a letter from Chapaev's daughter from Hungary with a detailed description of the death of the division commander. The investigation conducted by the Whites also confirms these data, according to the captured Red Army soldiers, “Chapaev, leading a group of Red Army soldiers at us, was wounded in the stomach. The wound turned out to be so severe that he could no longer direct the battle after that and was transported across the Urals on boards ... he [Chapaev] was already on the Asian side of the river. Ural died from a wound in the stomach.

The place where Chapaev was supposedly buried is now flooded - the riverbed has changed.

In the battles for Lbischensk, the commander of a special combined detachment of the White Guard Ural Army, the head of the operation, Major General (posthumously) Nikolai Nikolayevich Borodin, also died.

Vasily Chapaev. Legendary person

Other versions of the death of Vasily Chapaev

Textbook, thanks to Furmanov's book and especially the film "Chapaev", was the version of the death of the wounded Chapaev in the waves of the Urals.

This version arose immediately after the death of Chapaev and was, in fact, the fruit of an assumption, based on the fact that Chapaev was seen on the European coast, but he did not sail to the Asian (“Bukhara”) coast, and his corpse was not found - as is clear from the conversation on straight wire between a member of the Revolutionary Military Council of the 4th Army, I.F. Sundukov, and the temporary military commissar of the division, M.I. Sysoykin: "Sundukov:" Comrade Chapaev, apparently, was at first slightly wounded in the arm and, during a general retreat to the Bukhara side, he also tried to swim across the Urals, but had not yet entered the water, when he was killed by a random bullet in the back of the head and fell near the water, where he remained "... Sysoikin: "Regarding Chapaev, this is correct, such testimony was given by the Cossack to the residents of the Kozhekharovsky outpost, the latter handed it over to me. But on the shore There were a lot of corpses lying around the Urals, Comrade Chapaev was not there. He was killed in the middle of the Urals and drowned to the bottom."

However, this is not the only version of Chapaev's death. In our time, versions appear in the press that Chapaev was killed in captivity. They are based on the following.

On February 5, 1926, the Penza newspaper Trudovaya Pravda published an article “Man-beast” about the arrest in Penza by the OGPU of the Kolchak officer Trofimov-Mirsky, who allegedly commanded a combined detachment consisting of four Cossack regiments and operating in the Red Fourth Army, was distinguished sadistic reprisals against prisoners and, in particular, captured and chopped Chapaev and his entire staff. In Penza, Trofimov-Mirsky worked as an accountant for an artel of the disabled. Then this information appeared in Krasnaya Zvezda (under the heading "The murderer of Comrade Chapaev arrested") and was reprinted by a number of provincial newspapers.

Along with mass burnings alive and other episodes of brutal mass executions of prisoners, the investigation accused the 30-year-old Yesaul of allegedly ordering the slaughter of the captive Chapaev. It is further stated that “when the Chapaev division retreated from the village of Sakharnaya in the direction of the city of Lbischensk, Ural region in early October 1919, he Trofimov-Mirsky with his detachments drove into the rear of the Chapaev division for 80 miles and early in the morning at dawn attacked the headquarters of the Chapaev division in the city of Lbischensk, where, on his orders, the commander of the division comrade was brutally killed. Chapaev, and also all the teams located at the headquarters of the division in the city of Lbischensk were cut down.

This phrase of the accusation, however, is full of contradictions to the established facts: Chapaev died not in early October, but in early September, the retreat of the division did not precede the death of Chapaev, but was its consequence, Trofimov-Mirsky definitely was not and could not be the commander of the detachment that attacked Lbishensk (it is noteworthy that in the text of the note to the captain, that is, the junior officer, command of a detachment equal to a division is no longer attributed, as the investigation originally stated), and the distance traveled by the Cossacks during the raid is almost twice as long (150 miles).

Trofimov-Mirsky himself denied the accusations, admitting only that he really was disguised as a spy in the position of the division. He claimed that he had no more than 70 people in the detachment, and with this detachment he allegedly only "hidden in the Kyrgyz steppes." Apparently, the accusations were not confirmed, because in the end, Trofimov-Mirsky was released. It is significant that this case was initiated shortly after the release of Furmanov's sensational novel "Chapaev" (1923).

Professor Aleksey Litvin reports that back in the 1960s, a certain person was working as a carpenter in Kazakhstan, whom many (even Chapaev veterans) considered to be the surviving Chapaev, who “surfaced, was picked up by steppe Kazakhs, suffered from typhoid fever, after which he lost his memory.”

Some historians express the opinion that the role of Chapaev in the history of the Civil War is very small, and it would not be worth mentioning him among other famous figures of that time, such as N. A. Shchors, S. G. Lazo, G. I. Kotovsky, if would not be a myth created from it.

According to other sources, the 25th division played a big role in the zone of the South-Eastern Red Front in taking such provincial centers in the defense of Admiral Kolchak's troops as Samara, Ufa, Uralsk, Orenburg, Aktyubinsk.

Subsequently, after the death of Chapaev, the operations of the 25th Infantry Division were carried out under the command of I. S. Kutyakov in the Soviet-Polish war.

Personal life of Vasily Chapaev:

In 1908, Chapaev met 16-year-old Pelageya Metlina, the daughter of a priest. On July 5, 1909, 22-year-old Vasily Ivanovich married a 17-year-old peasant woman from the village of Balakovo Pelageya Nikanorovna Metlina (State Archive of the Saratov Region F. 637. Op. 7. D. 69. L. 380 ob - 309.).

Together they lived for 6 years, they had three children. Then the first began World War, and Chapaev went to the front. Pelageya lived in the house of his parents, then went with the children to a neighbor-conductor.

At the beginning of 1917, Chapaev drove to his native places and intended to divorce Pelageya, but was content with taking the children from her and returning them to their parents' house.

Pelageya (legitimate wife of Vasily Ivanovich), having learned that Vasily is no more, she decided to take her children. But soon, pregnant with her fifth child - the second from her roommate Makar, she went across the frozen Volga to her father-in-law, but fell into a hole. She caught a bad cold, gave birth to a dead boy and died.

Soon after that, he got along with Pelageya Kamishkertseva, the widow of Peter Kamishkertsev, a friend of Chapaev, who died from a wound during the fighting in the Carpathians (Chapaev and Kamishkertsev promised each other that if one of the two was killed, the survivor would take care of the friend's family).

In 1919, Chapaev settled Kamishkertseva with their children (Chapaev's children and Kamishkertsev's daughters Olimpiada and Vera) in the village. Klintsovka at the artillery warehouse of the division, after which Kamishkertseva cheated on Chapaeva with the head of the artillery warehouse Georgy Zhivolozhnov. This circumstance was revealed shortly before the death of Chapaev and dealt him a strong moral blow.

Pelageya Kameshkertseva dreamed of becoming Chapaev's real wife, but she could not. She blamed her appearance for everything, complained about her thick legs, rough hands with short fingers, and did not understand that she had got a monogamous. Out of grief, she decided to take revenge on Vasily in her own way - to cheat on him too. Her boyfriend Zhivolozhinov, after the death of Chapaev, took custody of his children, but he himself could not stand them. Over time, he abandoned his aged cohabitant. After that, the unfortunate Pelageya went crazy. Periodically treated in psychiatric clinics, she lived until 1961.

Pelageya Kamishkertseva - Vasily Chapaev's mistress (in the center)

AT Last year In his life, Chapaev also had affairs with a certain Tanka the Cossack (daughter of a Cossack colonel, with whom he was forced to part under the moral pressure of the Red Army) and the wife of Commissar Furmanov, Anna Nikitichnaya Steshenko, which led to a sharp conflict with Furmanov and caused Furmanov to be recalled from the division shortly before Chapaev's death.

Chapaev's daughter Claudia was sure that it was Pelageya Kamishkertseva who killed him. She described the circumstances of the family drama as follows: “Dad comes home one day - he looks, and the door to the bedroom is closed. He knocks, asks his wife to open it. on the other hand, they broke the window and let's shoot from a machine gun. The lover jumped out of the room and began to shoot with a revolver. My father and I miraculously escaped".

Chapaev, according to her, immediately went back to the division headquarters. Soon after that, Pelageya decided to make peace with her common-law husband and went to Lbischensk, taking little Arkady with her. However, she was not allowed to see Chapaev. On the way back, Pelageya drove into the white headquarters and reported information about the small number of forces standing in Lbischensk.

According to K. Chapaeva, she heard Pelageya boast about this already in the 1930s. However, it should be noted that since the population of Lbischensk and its environs, which consisted of the Ural Cossacks, fully sympathized with the whites and maintained contact with them, the latter were aware of the situation in the city in detail. Therefore, even if the story of the betrayal of Pelageya Kamishkertseva is true, the information she reported was not of particular value. This report is not mentioned in the documents of the White Guards.

Alexander Vasilievich(1910-1985) - officer, went through the entire Great Patriotic War. He retired with the rank of Major General. The last post was Deputy Commander of Artillery of the Moscow Military District. Raised three children. He died in March 1985.

Claudia Vasilievna(1912-1999) - Soviet party worker, known as a collector of materials about her father.

After the death of her father and the death of his parents, Claudia was literally on the street. She lived with thieves in the slums, was a dystrophic, as a result of a raid she ended up in an orphanage. Her stepmother took her only in 1925 to go with her to arrange a boarding house. At the age of 17, Claudia left her for Samara, got married, gave birth to a son, and entered a construction institute. During the Great Patriotic War she worked in the Saratov regional party committee. After the war, she became a people's assessor. She retired due to illness and asked the government for permission to work in the state archives, devoting the rest of her life to researching the history of her legendary father. She died in September 1999.

Arkady Vasilievich(1914-1939) - military pilot, since 1932 a member of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, died near Borisoglebsk during a training flight on a fighter.

At the age of 18 he was elected to the All-Russian Central executive committee. In Borisoglebsk he graduated flight school and together with he developed schemes for new test flights .. Later, having learned that they did not believe him and were suspected of organizing the death of Chkalov in order to take his place, that his own wife spied on him and wrote denunciations to various authorities, Arkady could not bear the shame. On his last flight, he left in an excited state, having completed the flight program, made another farewell coup and dived into the swamp. The crashed plane was found three days later.

Chapaev did not immediately become a legend: the death of the head of a division during the Civil War was not something exceptional. Chapaev's myth took shape over several years. The first step towards the glorification of the 25th division commander was the novel by Dmitry Furmanov, where Chapaev was shown as a nugget and, despite his simplicity, excessive gullibility and a penchant for self-praise, a real folk hero.

The myth of an invincible commander and "father to soldiers" finally took shape in the mid-1930s. The film of the brothers (in fact, namesakes) Georgy and Sergey Vasiliev met some obstacles on its way. The directors had to prove to the film authorities the need to create a sound (and not a silent film), the script was reworked according to the wishes of the country's main moviegoer - who "recommended" adding a romantic motive to the film: the relationship between Petka and Anka the machine gunner.

Such attention to the film was not accidental: the cinema was most important way propaganda and planting the "correct" worldview among the masses. The fate of the release or ban of films was decided on the high level, during their preview by members of the Politburo. On November 4, 1934, the party Areopagus watched Chapaev.

“When the tape ended, I. V. got up and, turning to me, said: “You can be congratulated on your luck. Healthy, cleverly and tactfully done... The film will be of great educational value. It is a good holiday gift. I. V. and others praised the work as brilliant, truthful and talented, ”wrote Boris Shumyatsky, party cinema curator.

Vasily Chapaev in culture and art:

In 1923, the writer Dmitry Furmanov, who served as a commissar in Chapaev's division, wrote a novel about him. "Chapaev". In 1934, based on the materials of this book, the directors Vasiliev brothers staged a film of the same name, which gained immense popularity in the USSR. The main role - Chapaev - was played by an actor.

Chapaev's success was deafening: over 40 million viewers saw him in two years, and Stalin watched him 38 (!) times in a year and a half. The queues at the box office turned into demonstrations.

However, this popularity has a downside. In the conditions of Soviet society, folklore developed in many respects in defiance of official propaganda, profaning its main dogmas and images. This is exactly what happened with the image of Chapaev and other characters in Furmanov's book and Vasiliev's film. As a result, division chief Vasily Ivanovich, his orderly Petka, commissar Furmanov and machine gunner Anka were among the most popular.

stills from the film "Chapaev"

At the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, director V. Petrov shot a short propaganda film "Chapaev is with us", which revived the national heroes. The cast is the same as that of the Vasilievs. The legendary hero is not killed, but safely sailed to the other side of the Urals. And his living orderly, Petka, throws a cloak around his shoulders, white horse. And Chapai tells the Red Army soldiers on all fronts what a hero can say to those who are "four steps away" from heroism.

The development of folk images continues in modern Russian literature (Viktor Pelevin, "Chapaev and Emptiness") and popular culture (series computer games"Petka").

Films about Vasily Chapaev:

"Chapaev" (film, 1934) (as Chapaev -);

"Song of Chapaev" (cartoon, 1944);

"Chapaev with us" (propaganda film, 1941) (as Chapaev - Boris Babochkin);

"The Tale of Chapaev" (cartoon, 1958);

"The Eaglets of Chapai" (film, 1968);

"Chapaev and Void" (book, 1997);

“The Politburo cooperative, or It will be a long farewell” (film, 1992) (as Chapaev - Vasily Bochkarev);

"Park of the Soviet period" (film, 2006). In the role of Chapaev -;

"Passion for Chapay" (TV series, 2012). Starring - ;

"Chapaev-Chapaev" (film 2013), director Viktor Tikhomirov, in the role of Chapaev;

"Kill Drozd" (TV series, 2013). In the role of Chapaev -;

"Temporary worker" (TV series, 2014), 3rd film "Save Chapay" (5 and 6 series). In the role - Denis Druzhinin;

"Little Buddha's Little Finger" / "Chapaev and Emptiness" (Buddha's Little Finger, 2015) (as Andre Hennicke Chapaev).

Songs about Chapaev:

"Song of Chapaev" (music: A. G. Novikov, lyrics: S. V. Bolotin, performs: P. T. Kirichek);

“Chapaev the Hero Walked in the Urals” (lyrics: M. A. Popova, performs: Red Banner Song and Dance Ensemble of the Soviet Army);

"The Death of Chapaev" (music: Y. S. Milyutin, lyrics: Z. Alexandrova, performs: A. P. Korolev);

“Chapai remained alive” (music: E. E. Zharkovsky, lyrics: M. Vladimov, performer: BDKh);

"Chapai" (music and lyrics: Ilya Prozorov, performs: group "Neboslov");

"AT. I. Ch.” (music and lyrics: performs: group "Front");

“Snack from Chapaev” (music and lyrics: Sergey Stus: performed by: group “Narcotic Comatosis”).

Books about Chapaev:

On the battle path of Chapaev. Brief guide. - Kuibyshev: Ed. gas. "Red Army", 1936;

Essay on V. Chapaev. V. A. Ivanov, Museum of V. I. Chapaev in Cheboksary;

D. A. Furmanov. Chapaev;

Arkady Severny. Tragedy Night". A play in one act. From the heroic history of the 25th Red Banner Order of Lenin Chapaev Division .. - M .: Art, 1940;

Timofey Timin. Scipio genes. Page 120 ff.: Chapaev - real and imaginary. M., "Veteran of the Motherland", 1997;

Khlebnikov N. M., Evlampiev P. S., Volodikhin Ya. A. Legendary Chapaevskaya. - M.: Knowledge, 1975;

Vitaly Vladimirovich Vladimirov. Where V. I. Chapaev lived and fought: travel notes, 1997;

Viktor Banikin. Stories about Chapaev. - Kuibyshev: Kuibyshev book publishing house, 1954;

Kononov Alexander. Stories about Chapaev. - M.: Children's literature, 1965;

Alexander Vasilievich Belyakov. Flying through the years. - M.: Military Publishing, 1988;

Evgenia Chapaeva. My unknown Chapaev. - M.: Corvette, 2005;

Sofia Mogilevskaya. Chapayonok: a story. - M.: Detgiz, 1962;

Mikhail Sergeevich Kolesnikov. All hurricanes in the face: a novel. - M.: Military Publishing, 1969;

Mark Endlin. Chapaev in America and others - Mixed (S.I.), 1980;

Alexander Markin. Adventures of Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev behind enemy lines and on the front of love. - M .: Idz-vo "Mik", 1994;

Edward Volodarsky. Passion for Chapai. - M.: Amphora, 2007;

V. Pelevin. Chapaev and Void. - M.: Amphora.

130 years ago, on January 28 (February 9, New Style), 1887, a hero of the Civil War was born. There is probably no more unique person in Russian history than Vasily Ivanovich Chapaev. His real life was short - he died at the age of 32, but posthumous fame surpassed all conceivable and inconceivable boundaries.

Among the real historical figures of the past, one cannot find another who would become an integral part of Russian folklore. What to talk about if one of the varieties of checkers games is called "chapaevka".

Chapai's childhood

When on January 28 (February 9), 1887, in the village of Budaika, Cheboksary district, Kazan province, the sixth child was born in the family of the Russian peasant Ivan Chapaev, neither mother nor father could even think about the glory that awaits their son.

Rather, they thought about the upcoming funeral - the baby, named Vasenka, was born seven months old, was very weak and, it seemed, could not survive.

However, the will to live was stronger than death- the boy survived and began to grow to the delight of his parents.

Vasya Chapaev did not even think about any military career - in poor Budaika there was a problem of everyday survival, there was no time for heavenly pretzels.

The origin of the family name is interesting. Chapaev's grandfather, Stepan Gavrilovich, was engaged in unloading timber and other heavy cargo floating down the Volga at the Cheboksary pier. And he often shouted “chap”, “chain”, “chap”, that is, “cling” or “hooking”. Over time, the word "chepay" stuck to him as a street nickname, and then became the official surname.

It is curious that the red commander himself subsequently wrote his last name precisely as “Chepaev”, and not “Chapaev”.

The poverty of the Chapaev family drove them in search of a better life to the Samara province, to the village of Balakovo. Here, Father Vasily had a cousin who acted as a patron of the parish school. The boy was assigned to study, hoping that over time he would become a priest.

Heroes are born of war

In 1908, Vasily Chapaev was drafted into the army, but a year later he was dismissed due to illness. Even before leaving for the army, Vasily started a family by marrying the 16-year-old daughter of a priest, Pelageya Metlina. Returning from the army, Chapaev began to engage in a purely peaceful carpentry trade. In 1912, while continuing to work as a carpenter, Vasily moved to Melekess with his family. Until 1914, three children were born in the family of Pelageya and Vasily - two sons and a daughter.

The whole life of Chapaev and his family was turned upside down by the First World War. Called up in September 1914, Vasily went to the front in January 1915. He fought in Volhynia in Galicia and proved himself to be a skilled warrior. Chapaev finished the First World War with the rank of sergeant major, being awarded the soldier's St. George's crosses of three degrees and the St. George medal.

In the autumn of 1917, the brave soldier Chapaev joined the Bolsheviks and unexpectedly showed himself to be a brilliant organizer. In the Nikolaevsky district of the Saratov province, he created 14 detachments of the Red Guard, which took part in the campaign against the troops of General Kaledin. On the basis of these detachments, in May 1918, the Pugachev brigade was created under the command of Chapaev. Together with this brigade, the self-taught commander recaptured the city of Nikolaevsk from the Czechoslovaks.

The fame and popularity of the young commander grew before our eyes. In September 1918, Chapaev led the 2nd Nikolaev division, which instilled fear in the enemy. Nevertheless, the steep temper of Chapaev, his inability to obey unquestioningly led to the fact that the command considered it a good thing to send him from the front to study at the Academy of the General Staff.

Already in the 1970s, another legendary red commander Semyon Budyonny, listening to jokes about Chapaev, shook his head: “I told Vaska: study, you fool, otherwise they will laugh at you! So you didn’t listen!”

Ural, Ural River, his grave is deep...

Chapaev really did not stay long at the academy, again going to the front. In the summer of 1919, he led the 25th Rifle Division, which quickly became legendary, as part of which he carried out brilliant operations against Kolchak's troops. On June 9, 1919, the Chapaevs liberated Ufa, on July 11 - Uralsk.

During the summer of 1919, Divisional Commander Chapaev managed to surprise the regular white generals with his talent as a commander. Both comrades-in-arms and enemies saw in him a real military nugget. Alas, Chapaev did not have time to really open up.

The tragedy, which is called Chapaev's only military mistake, occurred on September 5, 1919. Chapaev's division was rapidly advancing, breaking away from the rear. Parts of the division stopped to rest, and the headquarters was located in the village of Lbischensk.

On September 5, whites numbering up to 2000 bayonets under the command of General Borodin, having made a raid, suddenly attacked the headquarters of the 25th division. The main forces of the Chapayevites were 40 km from Lbischensk and could not come to the rescue.

The real forces that could resist the whites were 600 bayonets, and they entered into battle, which lasted six hours. He hunted for Chapaev himself special squad which, however, did not succeed. Vasily Ivanovich managed to get out of the house where he lodged, gather about a hundred fighters who were retreating in disorder, and organize defense.

For a long time, conflicting information circulated about the circumstances of Chapaev's death, until in 1962 the daughter of division commander Claudius received a letter from Hungary in which two Chapaev veterans, Hungarians by nationality, who were personally present during the last minutes of the division commander's life, told what really happened.

During the battle with the whites, Chapaev was wounded in the head and stomach, after which four Red Army soldiers, having built a raft from the boards, managed to transport the commander to the other side of the Urals. However, Chapaev died of his wounds during the crossing.

The Red Army soldiers, fearing the mockery of the body by the enemies, buried Chapaev in the coastal sand, throwing branches at this place.

An active search for the grave of the divisional commander was not carried out immediately after the Civil War, because the version set forth by the commissar of the 25th division Dmitry Furmanov in his book “Chapaev” became canonical - as if the wounded divisional commander drowned while trying to swim across the river.

In the 1960s, Chapaev's daughter tried to search for her father's grave, but it turned out that this was impossible - the channel of the Urals changed its course, and the bottom of the river became the final resting place of the red hero.

Birth of a legend

Not everyone believed in Chapaev's death. Historians involved in the biography of Chapaev noted that among the Chapaev veterans there was a story that their Chapai swam out, was rescued by the Kazakhs, had typhoid fever, lost his memory and now works as a carpenter in Kazakhstan, remembering nothing about his heroic past.

Fans of the white movement love to give the Lbischensky raid great importance, calling it a major victory, but it is not. Even the defeat of the headquarters of the 25th division and the death of its commander did not affect the overall course of the war - the Chapaev division continued to successfully destroy enemy units.

Not everyone knows that the Chapayevites avenged their commander on the same day, September 5th. General Borodin, commander of the white raid, who was victoriously passing through Lbischensk after the defeat of Chapaev's headquarters, was shot by a Red Army soldier Volkov.

Historians still cannot agree on what was actually the role of Chapaev as a commander in civil war. Some believe that he really played a prominent role, others believe that his image is exaggerated due to art.

Studying the life of Chapaev, you are surprised to find how closely the legendary hero is connected with other historical figures.

For example, the fighter of the Chapaev division was the writer Yaroslav Gashek, the author of The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schweik.

The head of the trophy team of the Chapaev division was Sidor Artemyevich Kovpak. In the Great Patriotic War, the mere name of this commander of a partisan unit will terrify the Nazis.

Major General Ivan Panfilov, whose division's resilience helped defend Moscow in 1941, began his military career as a platoon commander in an infantry company of the Chapaev division.

And the last. Water is fatally connected not only with the fate of division commander Chapaev, but also with the fate of the division.

The 25th Rifle Division existed in the ranks of the Red Army until the Great Patriotic War, took part in the defense of Sevastopol. It was the fighters of the 25th Chapaev division who fought to the last in the most tragic, last days city defense. The division was completely destroyed, and so that the enemy did not get its banners, the last surviving soldiers drowned them in the Black Sea.

Academy student

Chapaev's education, contrary to popular belief, was not limited to two years of parochial school. In 1918, he was enrolled in the military academy of the Red Army, where many fighters were "driven" to improve their general literacy and strategy training. According to the memoirs of his classmate, the peaceful student life weighed heavily on Chapaev: “Damn it! I'm leaving! To come up with such nonsense - fighting people at a desk! Two months later, he filed a report with a request to release him from this "prison" to the front. Several stories have been preserved about Vasily Ivanovich's stay at the academy. The first says that in a geography exam, in response to a question from an old general about the significance of the Neman River, Chapaev asked the professor if he knew about the significance of the Solyanka River, where he fought with the Cossacks. According to the second, in a discussion of the battle of Cannae, he called the Romans "blind kittens", telling the teacher, a prominent military theorist Sechenov: "We have already shown generals like you how to fight!"

Motorist

We all imagine Chapaev as a courageous fighter with a fluffy mustache, a naked saber and galloping on a dashing horse. This image was created by the national actor Boris Babochkin. In life, Vasily Ivanovich preferred cars to horses. Even on the fronts of the First World War, he received a serious wound in the thigh, so riding became a problem. So Chapaev became one of the first red commanders who moved to the car. He chose iron horses very meticulously. The first - the American "Stever", he rejected due to strong shaking, the red "Packard", which replaced him, also had to be abandoned - he was not suitable for military operations in the steppe. But the "Ford", which squeezed 70 miles off-road, the red commander liked. Chapaev also selected the best drivers. One of them, Nikolai Ivanov, was practically taken to Moscow by force and put as the personal driver of Lenin's sister, Anna Ulyanova-Elizarova.

"... It is curious that the red commander himself subsequently wrote his last name exactly as "Chepaev", and not "Chapaev".

I wonder how he was supposed to write his last name if he was Chepaev? Chapaev was made by Furmanov and the Vasiliev brothers. Before the release of the film on the screens of the country, on the monument to the commander in Samara it was written - Chepaev, the street was called Chepaevskaya, the city of Trotsk - Chepaevsk, and even the river Mocha was renamed Chepaevka. In order not to embarrass the minds of Soviet citizens in all these toponyms, "CHE" was changed to "CHA".