A long time ago, about twenty-five or thirty years ago, an event occurred at the Faculty of Biology of the N-University.

This event was quite insignificant, but nevertheless for some time it caused general bewilderment.

At the very end of July, shortly after the graduation party of the faculty, it became known that Bob was left at the university from among the graduates ...

The man who wore this nickname, forever stuck to him, was already middle-aged at that time - he was in his forties. Although he had a tall and generally prominent figure, the most noticeable detail of his appearance was still a beaver hairstyle of some piebald, indeterminate color of hair.

Every time the exams began at the faculty and Bob sat down at the professor's table with an exam card in his left hand, with his right hand he took out a miniature comb in a silver frame from the side pocket of a gray paramilitary and slightly shabby jacket and with a few unhurried, confident movements brought the formation to full order. piebald short and elastic hair on his head.

Then, without waiting for an invitation, he groped for a point of support on the professor's table with his elbow, clenched his fingers into a fist and, leaning on this fist with his already graying temple, began to speak.

His voice was unhurried, very muffled, and with such a peculiar intonation that all the time made the listener expect that right now, this minute, this very second, that very innermost essence, for the sake of which people are talking and intending to please each other, will be uttered, cheer up, enrich something. The examiner waited for this essence, nodding encouragingly and even friendly.

Five, ten minutes passed, and the examiner lost the thread of reasoning of the no longer young, tall and so modest student. For a moment, the examiner thought about an extraneous subject, about, for example, how many students have already passed exams today and how many are left, or he remembered that he must definitely call his wife, say that she should not wait for dinner, although as recently as yesterday he promised never to be late again. And at that very moment, the muffled, measured voice fell silent.

The examiner began to stare at the ceiling, trying in vain to remember how the student completed his reasoning on this issue.

Whitish eyes were also looking at him from under whitish eyelashes. These eyes and the whole face - slightly wrinkled, very serious, under a high forehead and a piebald beaver - reflected the good-natured fatigue of a man who had done a good job.

N-yes ... - said the examiner. - So ... so ... well, answer the next question! - And internally pulling himself up, he promised himself to listen to the student carefully, not missing anything.

The muffled voice again filled the office with the expectation of something significant; then this unexpressed significance tired attention, the professor again recalled that he needed to call his wife, remembered, it seems, for only one moment, and immediately came across the good-natured, very serious face of a man who was fairly tired and silent from fatigue ... In his whitish eyes there was now reproach.

N-yes ... So ... Well, then, answer the next, third question!

Bob usually got a "four" in his exams. He got up from his seat, smoothed the beaver with a comb, slowly collected the papers, smiled and left. The smile was significant, but indefinite - it could also be understood as a spiritual reproach of the student to himself for not answering "excellent", and she also expressed bewilderment: why was the examiner inattentive after all?

Classmates did not like Bob and did not hide their attitude towards him.

Professors and teachers, if the conversation between them happened to concern Bob, shrugged their shoulders and sighed a little bewildered and somehow indefinitely.

The indefinite attitude of teachers towards an elderly student continued until he moved to the fourth year. In the fourth year there was an exam in the most extensive section of zoology, and it was then that the head of the department, a candidate for corresponding members of the Academy in the next elections, Professor Karabirov, a short, angry, quick-tempered man, suddenly spoke quite definitely in the dean's office:

Invertebrate rodent! Karabirov said. - From each discipline knows two pages. Two - from Timiryazev. Two are from Darwin. Two - from Mechnikov. He knows, however, firmly, by heart. And imagine, this, it turns out, is quite enough to study at our well-deserved biology faculty, to study with decent grades in matricules!

One might think that these words were spoken by Karabirov in defiance of his eternal adversary - the dean.

The dean was still relatively young at that time, a professor - a geobotanist with a Russian name and a Greek surname - Ivan Ivanovich Spandipandupolo. Karabirov assured that such a surname confirms that even in the process of embryonic development, its owner lost all common sense.

Spandipandupolo had a rule not to remain indebted to Karabirov, but at that time, when the conversation turned to Bob, unexpectedly for everyone, he kept silent. And then everyone understood that the zoologist would definitely “slaughter” Bob in the exam, and they breathed a sigh of relief: it was necessary for one person to do the very thing that many had to do a long time ago ...

The short silence that reigned in the darkish, narrow and high room of the dean's office now unequivocally explained the attitude of the Precedents to the student, whom everyone knew not only by his last name, but by his short nickname "Bob".

However, for Bob, this was not at all the beginning of the end of his scientific career, as one might think then.

Indeed, the "invertebrate rodent" went to take the exam in zoology twice and failed both times. Then he got sick. Then, due to illness, he postponed the exams to the next year of study. All this was the usual course of action for such a case, and the dean was about to issue an order for expulsion, or at least for a year's leave of Bob, when suddenly this Bob brought a mark in zoology for registration with the secretary of the faculty: "four"!

Of course, at the very first meeting, Spandipandupolo did not fail to ask Karabirov:

I heard, colleague, your favorite student - sorry, I forgot the last name - brilliantly passed your course?

Without specifying who he was talking about, Karabirov took the hint from the dean's too gracious tone alone, jumped out of the old leather chair in which he always sat down when he was in the dean's office, and banged his fists on this chair:

What can I do? What can I do, I ask you? Who skipped the rodent until his senior year at university? Who? Only teachers worthy of their student could do this! Only they! Not me! I have nothing to do with this! No!

The evil little Karabirov again sank into a deep armchair, from which now only his grey, disheveled, and also angry beard was sticking out, and fell silent. And after some time, a quiet, unusually peaceful voice for Karabirov suddenly came:

After all, it's our job now to release it. Release, release! Hands emerged from the chair, almost politely but insistently pushing someone away. - Release! If only he were even dumber! Quite, quite a bit dumber ... But he still has something in his skull that somehow allows him to finish ... Rarely, very rarely, but still there are people with even less abilities and with university diploma. We also released them, and more than once.

And again, Dean Spandipandupolo did not take the opportunity to prick Karabirov, who had long ago bored the entire faculty with insolence. On the contrary, just like the time when Karabirov made it clear that he would "slaughter" Bob, now everyone felt relieved again. Indeed, there is little left - to release a person. And the end. After all, in fact, there were students even weaker. It happened. This one, after all, but gets fours, there are also those who are interrupted from two to three.

7 139

Throughout its history, mankind has accumulated a lot of facts testifying to the existence of such an inexplicable phenomenon as time travel. The appearance of strange people, machines and mechanisms is recorded in the historical annals of the era of the Egyptian pharaohs and the dark Middle Ages, the bloody period of the French Revolution, the First and Second World Wars.

Programmer in the 19th century

In the archives of Tobolsk, the case of a certain Sergei Dmitrievich Krapivin, who was detained by a policeman on August 28, 1897, on one of the streets of this Siberian city, has been preserved. The suspicion of the law enforcement officer was caused by the strange behavior and appearance of a middle-aged man. After the detainee was taken to the station and began to be interrogated, the police were quite surprised by the information that Krapivin sincerely shared with them. According to the detainee, he was born on April 14, 1965 in the city of Angarsk. No less strange to the policeman seemed his occupation - a PC operator. How he got to Tobolsk, Krapivin could not explain. According to him, shortly before that, he had a severe headache, then the man lost consciousness, and when he woke up, he saw that he was in a completely unfamiliar place not far from the church.

A doctor was called to the police station to examine the detainee, who admitted that Mr. Krapivin was insane and insisted on placing him in a city lunatic asylum...

Shard of Imperial Japan

A resident of Sevastopol, retired naval officer Ivan Pavlovich Zalygin has been studying the problem of time travel for the last fifteen years. The captain of the second rank became interested in this phenomenon after a very curious and mysterious incident that happened to him in the late 80s of the last century in the Pacific Ocean, while serving as deputy commander of a diesel submarine. During one of the training trips in the area of the La Perouse Strait, the boat got into a severe thunderstorm. The submarine commander decided to take a surface position. As soon as the ship surfaced, the sailor on duty reported that he saw an unidentified floating craft right on the course. It soon becomes clear that a Soviet submarine stumbled upon a lifeboat in neutral waters, in which the submariners found a half-dead frostbitten man in ... the uniform of a Japanese military sailor during the Second World War. When examining personal belongings of the rescued, a premium parabellum was found, as well as documents issued on September 14, 1940.

After the report to the base command, the boat was ordered to go to the port of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, where counterintelligence was already waiting for the Japanese military sailor. GRU officers took a non-disclosure agreement from the team members for the next ten years.

Napoleon's troops against tanks

In Zalygin's card file there is a case described by a certain Vasily Troshev, who fought as part of the third tank army of the North-Western Front. During the battles for the liberation of Estonia in 1944, not far from the Gulf of Finland, a tank reconnaissance battalion commanded by Captain Troshev stumbled upon a strange group of cavalrymen in a wooded area, dressed in a uniform that tankers saw only in history books. The sight of the tanks sent them into a stampede. As a result of a short pursuit through the wetlands, our soldiers managed to detain one of the cavalrymen. The fact that he spoke French greatly endeared the Soviet tankers to the prisoner, who knew about the Resistance movement and mistook the cavalryman for a soldier of the allied army.

The French cavalryman was taken to the army headquarters, they found an officer who taught French in his pre-war youth, and with his help they tried to interrogate the soldier. Already the first minutes of the conversation perplexed both the interpreter and the staff officers. The cavalryman claimed that he was a cuirassier in the army of Emperor Napoleon. At present, the remnants of his regiment, after a two-week retreat from Moscow, are trying to get out of the encirclement. However, two days ago they got into heavy fog and got lost. The cuirassier himself said that he was extremely hungry and had a cold. When asked by the translator about the year of birth, he said: one thousand seven hundred and seventy-two ...

Already in the morning of the next day, the mysterious prisoner was taken away in an unknown direction by the arrived officers of the special department ...

Is there a chance to return?

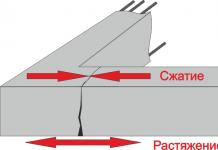

According to I.P. Zalygin, there are a number of places on the planet in which the facts of temporary movements occur quite often. It is in these places that large faults in the earth's crust are located. Powerful ejections of energies periodically come out of these faults, the nature of which is far from being fully understood. It is during periods of energy emissions that anomalous space-time movements occur both from the past to the future, and vice versa.

Almost always, temporary displacements are irreversible, but it happens that people who have moved against their will to another time have the good fortune to return again. So, Zalygin describes a case that occurred in the early nineties of the XX century on one of the foothill plateaus of the Carpathians with one of the shepherds. A man with his fifteen-year-old son was in a summer parking lot, when one evening, in front of a teenager, he suddenly disappeared. The shepherd's son began to call for help, but literally a minute later his father reappeared as if out of thin air in the same place. The man was extremely frightened and could not close his eyes all night. Only the next morning the shepherd told his son about what had happened to him. As it turned out, at some point the man saw a bright flash in front of him, lost consciousness for a moment, and when he woke up, he realized that he was in a completely unfamiliar place. Huge chimney-like houses stood around him, some machines scurried through the air. Suddenly the shepherd felt ill again, and he again found himself in the familiar parking lot ...

Ivan EVSEENKO

Sergey Zalygin and others...

Book one. Literary Institute

Sergei Pavlovich Zalygin was the head of the prose seminar at the Literary Institute. Gorky, where I studied in 1968-1973. I heard his name before entering the Literary Institute, but, to my shame, I did not read a single line from Zalygin's novels, stories and short stories. I had little interest in prose at that time. Firstly, because he considered himself by the rank of beginning poets, he was full of poetic passions and boiling, which then raged on the pages of the periodical press, and in numerous poetic circles, clubs, seminars, meetings that arose everywhere. And secondly, because, having recovered in 1966 to study at the Kursk Pedagogical Institute after serving in the army, I plunged into my studies with all my insatiability, diligently and diligently (for which I thank myself to this day) proofread the literature required by the program of the philological faculty , ranging from ancient - Greek and Latin - and ending with Old Russian. There was almost no time left for modern literature.

My admission to the Literary Institute was rather complicated and dramatic. I wrote about this in more detail in the chapters devoted to Evgeny Ivanovich Nosov and Alexander Alekseevich Mikhailov. Here I will only recall an episode connected with Sergei Pavlovich. At the interview that preceded the entrance exams, it turned out that I was a student of the philological faculty of the Kursk Pedagogical Institute, and not an employee of the district newspaper, as I wrote in the questionnaire at the prompt of Evgeny Ivanovich Nosov, sending my short parable stories to a creative competition. According to the then rules, students from related philological universities were not admitted to the Literary Institute. Severovy Alexander Alekseevich Mikhailov, Vice-Rector for Academic Affairs, put me out of the audience where the interview was held, put me out into the corridor. I walked out neither alive nor dead, almost saying goodbye to my dream of entering the Literary Institute. And outside the door, an interview began already between the teachers, what to do with me, with my deceit and cunning. (Afterward, however, it turned out that I was not the only one who was so smart and cunning. Many of my future classmates studied at “related” universities). And at this secret interview of teachers, Sergei Pavlovich interceded for me, whom I, to confess, for those few minutes that I sat in front of a strict commission, did not remember. And how could I remember him, when before that I had never even seen him even in photographs. In addition, he did not know at that moment that it was Zalygin who was recruiting a prose seminar. And he remembered and stood up for me and for Georgy Bazhenov, whose situation with admission was even worse than mine, Sergey Pavlovich somehow liked our stories. My parables, more like vers libres, and Bazhenov's folklore, written by him in distant hot India, where Georgy, Gera, a student at the Gorky Institute of Foreign Languages, worked as a translator.

I became acquainted with the work of Sergei Pavlovich during the entrance exams in the dormitory of the Literary Institute on Dobrolyubov Street. Four people settled in our room: Volodya Shirikov from Vologda, Gennady Kasmynin from Orenburg (both, unfortunately, long dead), Yura Bogdanov from Belarus, from the city of Baranovichi, and I - Kursk-Chernigov. Gena and Yura entered the department of poetry (the seminar was recruited by Evgeny Dolmatovsky). And both of them didn’t enter that year: Gena, in his youth, simply carelessly, carelessly, treated the exams, and Yura, a musician and bayan player by his initial education, was still doubting where he should go - to the Literary Institute or to the conservatory. They will enter the Literary Institute next year and, if I am not mistaken, they will get into Yegor Isaev's seminar.

Volodya Sharikov and I aimed at prose writers, storytellers and novelists. Volodya was more prepared in terms of knowledge of modern prose. And it was impossible for him, living in Vologda next to Vasily Ivanovich Belov and making acquaintance with him, not to be prepared. It was Volodya who enlightened me who Zalygin was, and what his name means in modern literature. Volodya was very happy that, in case of admission, we would get into the seminar with Zalygin. And for my ignorance, it seemed that it didn’t matter who would lead the seminar - the main thing was to enter.

Volodya gave me a collection of Sergei Pavlovich's stories to read. To be honest, they didn’t make a big impression on me, they seemed dry and boring. I expressed some rather decisive, maximalist thoughts about what I had read. Volodya did not agree with me. He had a different opinion about the work of Sergei Pavlovich and knew his true value. Volodya read not only Zalygin's stories, but also his famous story "On the Irtysh", the novel "Altai Paths" and the novel "Salty Pad", just published and nominated for the USSR State Prize.

Evgeny Ivanovich Nosov enlightened me even more intelligibly about Zalygin when, after my admission, I returned to Kursk to please him with my successes.

He is now on horseback, - Yevgeny Ivanovich figuratively said about Zalygin and, as it were, handed me over to him from hand to hand, knowing that these hands are strong and reliable.

It was difficult and even very difficult for me to pass the entrance exams to the Literary Institute. The words of Alexander Mikhailov, which he told me when he called me for an interview again after a meeting with the selection committee, pressed me with unbearable oppression:

Pass exams, since you arrived, but when enrolling, we will take into account your deceit!

How was it not to fall into despondency and despair after such words ?! I came, and I despaired. But nowhere to go, he began to intensively prepare for the exams.

The most important and, in general, determining all admission to the Lit Institute was a written exam in Russian literature - an essay. His entrants were most afraid of him. Much depended on what topics would be proposed for composition. Prior to the generally accepted rule in those years, applicants were given three topics to choose from: two strictly literary (according to classical literature of the 19th and 20th centuries) and one - free. The Literary Institute was no exception that year. The first topic concerned Mayakovsky and sounded something like this: "Innovation in the work of Vladimir Mayakovsky." Second: "Civil motives in the poetry of Nikolai Nekrasov." We expected something like this, although no one was seriously ready for these topics that require specific knowledge. Most of the applicants graduated from school five, and even ten years ago (I - eight), and all the specific school knowledge has disappeared from our smart heads.

All hopes were on the third topic - a free one, where one could reveal one's literary predilections, spread one's thoughts along the tree. On the eve of the exam, we wondered this way and that, what this free topic, so desirable for us, could be. Everyone was inclined to believe that, most likely, it would somehow affect the decisions of the last, in terms of terms, XXII Party Congress, which took place in 1966.

But we were deeply mistaken in our forecasts. The third topic was completely unexpected and really free of the free. Our fantasies here could play out both up and in breadth - "What kind of life do you imagine in 2000?".

The year was 1968, until 2000 it was still more than thirty years old, no one looked so far back then! The year 2000 was seen by everyone as an unrealistically happy horizon, behind which lurks in a haze, if not complete communism, then something very close to it. But the Literary Institute is the Literary Institute, and now one of its teachers (it would be interesting to know now - to whom?) came up with this great idea to puzzle future writers and poets with a similar topic.

It goes without saying that most of the applicants attacked her. Special, literary topics, as far as I know, only two people from our Zalygin seminar wrote: Georgy Bazhenov about Mayakovsky and Vladimir Shirikov about Nekrasov. So both of them were the most prepared of us in the knowledge of both classical and Soviet literature.

I did not tempt fate and took up a free topic. By that time, I already had considerable experience in passing exams, after all, two years of a pedagogical institute were behind me. Without further ado and fearing to make grammatical errors, in short sentences (subject, predicate, object), just like in my first prose attempts, I presented the topic quite pragmatically and historically correctly. Allegedly, the 221st Party Congress was recently held, it set three main tasks for the Soviet people: first, the creation of the material and technical base of communism; the second is the struggle for peace; and third, the education of the new man. By the year 2000, - I thoughtfully narrated - all these three tasks will be fulfilled to a certain extent. In order to show my knowledge in the field of modern literature, I added two or three paragraphs about my favorite villagers, who with their creativity contribute to the fulfillment of all three tasks set by the 221st Party Congress, and especially the last one - the education of a new person. Contributed or not contributed - the question, of course, is debatable: the future development of the country gave the most cruel answers to it. Not a trace remained of the material and technical base of communism. It is not only destroyed to the ground, but also anathematized along with its builders, former Soviet people. We have not painfully succeeded in the struggle for peace: the third world war, thank God, did not happen, but small, local wars are blazing all over the world. With the upbringing of a new person, the situation is quite bad. In one five-year period (in one five-year period) he was brought up on his own, without any party decisions. True, he acquired the name almost in accordance with these decisions - “new Russian”. But I wanted a “new Soviet” to emerge. After all, it was stated that a new community was formed in the Soviet Union - the Soviet people. Where is this people now, where is this community now?!

Maybe we prophesied with our frivolous writings in the distant 1968 the future disintegration and collapse, calling trouble on a great power?! But even then it must be said that even in the most feverish delirium we could not then think about him. We were children of our time - and still firmly believed in a bright future.

My grandiose plan succeeded. For the essay I was given a “four” (apparently, I did make two or three spelling or syntax errors), which I was very pleased with. Having slipped through this smallest examination sieve, I cheered up a little, cheered up. In the rest of the sieves, the cells were wider, with the possible exception of a foreign language, the German language, in mastering which I had problems since my school days. And maybe because I had no luck with German teachers. Only the very first teacher of the German language, hated by us, the children of war, Fedosya Konstantinova Komissarenko (she taught with us for only one year, in the fifth grade, and then went on maternity leave) knew him well and reliably, since she studied not at schools and institutes, but in Germany, where during the war she was driven away by other village girls. The rest did not call him much better than us, they were part-time teachers of history, geography and other subjects in their main specialties. They could not teach us anything worthwhile, they leaned more on dry grammar than on living spoken language, and we, feeling weak, were not painfully zealous in teaching.

But the next exam after the composition was not yet a foreign language, but an oral exam in the Russian language and Russian literature. I was not very afraid of this test. At the Pedagogical Institute, only a month and a half ago, I took an exam in morphology and syntax, in Russian literature of the first half of the 19th century, and managed to subtract a lot over the summer according to the program of the second half of the 19th century. So I even gave advice to guys who were not so experienced in morphology, syntax and linguistics.

I passed the exam in Russian literature to Valery Vasilievich Dementiev. What was the first question about the literature of the 19th century, I don’t remember now, but something I knew and knew well, which did not cause fear. The second question was about the article by V.I. Lenin "Party Organization and Party Literature" I also knew this confusing article by Lenin quite well, since I studied it at the seminars on the history of the CPSU at the same pedagogical institute.

I answered both questions well, and Valery Vasilievich gave me an “excellent” without even letting me speak to the end.

With a light heart, I moved to the table with the Russian language teacher Nina Vasilievna Fedorova, with whom I subsequently developed a very friendly, trusting relationship. But she unexpectedly gave me only a “four”, which, frankly, choked me a lot. It seemed to me that I answered both questions quite convincingly, without hesitation I made a morphological and syntactic analysis of some tricky sentence. But still, apparently, he made a mistake somewhere and deserved only a “four”. True, it did not affect the overall mark in the Russian language and literature. In the examination sheet, a single mark was put - and, to my joy, there appeared a “five”, which, it seems, Valery Dementieva insisted on.

But the next exam was fatal for me - in a foreign language.

I went to him neither alive nor dead, but even here luck accompanied me.

The exam was taken by a guest lecturer from Moscow State University, a very friendly young woman. The task in the ticket was not God knows what complexity. With the help of a dictionary, I had to translate a small fragment of a literary text, either from Hoffmann or from the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, and answer very primitive questions: “What is your name? Who are your parents? Where were you born?" etc. In general, everything is within the school curriculum. But as luck would have it, the passage turned out to be difficult. No matter how much I struggled with it, no matter how much I adjusted one word to another, and in the time allotted for preparation I managed to translate only half.

The teacher didn't seem to rush me very much, but she looked at me expectantly several times. And I decided to appear before her as soon as possible, it was no longer possible to delay. I read the text quite tolerably and even smartly, but I got confused with the translation, thinking with horror that I was about to have to confess my impotence before the tricky Hoffmann . And it must have happened that just at the last sentence I translated, the quick-witted teacher stopped me. Either she was tired of my stuttering, or she was satisfied with the knowledge of an unlucky applicant.

Questions from the field of German grammar (it still seems to me that the German language was invented for the sake of grammar) I answered without any special complications. Here in my head is something left from school and student knowledge: Perfekt, Amperfekt, Pluskuamperfekt.

But then came the most important test for me - a conversation about a teacher in German. I think that even after the first two questions everything was clear with me - I didn’t pull more than “satisfactory”. But she, looking at my examination sheet, where two high marks for previous exams proudly flaunted - “good” and “excellent” - nevertheless decided to try her luck: would I not stretch even here at least for “good”. And I began to draw out, in a school way to answer her most simple questions. I don’t know how I answered there, how I refined myself, but the matter nevertheless began to lean towards “good”, towards the “four” that I longed for. And then, unexpectedly, the secretary of the selection committee entered the audience (sorry, now I don’t remember her last name, first name and patronymic), who was a witness to all the complications I had at the interview. She asked the teacher some question of her own that interested her and was about to leave, but suddenly the teacher stopped her and, pointing to my examination sheet, in her turn asked in a half whisper:

If I give a young man a B, how will he pass?

The secretary of the examination committee also looked at the examination sheet, was silent for a few moments, and then, probably remembering the interview, answered with a completely transparent hint:

I don't know, but probably...

And hastily left the audience. The teacher hesitated for a minute, sighed, and again (already almost passionately) began to interrogate me about my last name, and about my place of birth, and about my parents. Again, with God's help, I answered all of her malicious of malicious questions. Whether she was satisfied with me or not, I don’t know, but at the end of the interrogation, with an unwavering hand, she suddenly wrote “excellent” in my examination sheet.

Danke schon! - I rewarded her for this act with my deepest knowledge in the field of the German language, that is: “Thank you very much!”.

For two hours, stunned by everything that had happened, I wandered through the red-hot August streets of Moscow. It was already a stroke of luck - before entering the Literary Institute, which I raved about and dreamed about so much, there was only one step left, just one exam in the history of the USSR, which I feared much less than all the other tests. Firstly, here, too, my pedagogical knowledge of the history of the CPSU was quite fresh in my memory (and this is the same as the history of the USSR of the Soviet period), and secondly, since my school days I firmly learned one rule for myself when answering in class history, and even more so in history exams. First of all, it is necessary to outline the socio-economic situation of the country in question. If the matter concerns war, uprising or rebellion, then here, too, it is first necessary to talk about the socio-economic and political causes of their occurrence, then about the reasons, and only after that proceed to the presentation of the events themselves. Many times such an ingenious design in answers on history helped me out. Before events and actions, that is, before specific knowledge, the matter often did not reach. The teacher stopped me, fully satisfied with the depth of my thinking and the correct view of historical processes from the point of view of Marxist-Leninist methodology. I counted on this even now when I passed my last entrance exam to the Literary Institute. Only the history of the USSR in the pre-revolutionary period caused me anxiety. But here I was hoping to calculate something for those two days that were allotted for preparing for the exam.

And suddenly we were told that on one of these days all applicants would have to undergo a medical examination at the Literary Fund's polyclinic. Who came up with this completely untimely thought, I do not know. After all, upon admission, all of us provided the admission committee with a mandatory medical certificate in form No. 246, where the state of our precious health was examined with all rigor. But someone decided that the certificate was not enough, and we were all in formation, as if recruit soldiers, tearing them away from textbooks, were taken across Moscow to the Litfond polyclinic at the Aeroport metro station. A day so important to me was irretrievably lost.

After reading something in a hurry in the evening and discussing it with Volodya Shirikov, whose knowledge of national history was stronger than mine, I decided that tomorrow I would get up early in the morning and start reading my textbooks in earnest. So I did. At six o’clock, having had a hasty breakfast, I covered myself with textbooks and maps and began to study the history of the Fatherland from the time of Rurik to the time of Lenin with unstoppable stubbornness and perseverance, knowing full well that we should get an “A” on the exam in history, then a harsh selection committee and more the more severe Alexander Alekseevich Mikhailov will have nowhere to go - I will have to be enrolled in the institute, because I will score 19 out of 20 hundred percent points. There are hardly many such applicants.

Through a wide, almost the entire wall window, the August sun shone brighter, brighter even at such an early time. It blinded my eyes, as if testing them for strength, but I did not pay any attention to this, not to life, but to death, I struggled over every page of the textbook.

And achieved! By evening, my eyes suddenly began to hurt quite noticeably, almost unbearable pains appeared in them, as if someone invisible had covered my eyes with coarse-grained river sand. Nothing like this had happened to me before, although during the exam sessions at the Pedagogical Institute I sat at the books not only all day, but also at night. And then it happened, it happened. It probably had an effect of strong nervous tension, stress, under the weight of which I had been under the weight for more than a month, starting from the day I arrived in Kursk to help out the matriculation certificate at the pedagogical institute, which I needed to enter a new university. Then (not like now!) it was strictly forbidden. If you want to enter a new institute, drop the old one, take the risk. Thank you, I was issued a certificate in Kursk at the direction of the then rector, who knew me well as an exemplary student, public figure - a member of the Komsomol committee responsible for issuing the Komsomol Searchlight.

Willy-nilly, I had to interrupt my studies, although these eye pains and cramps did not cause any particular alarm. In youth and carelessness, I thought: well, they will hurt and stop. Alas, they didn't stop. This day, August 18, 1968, became a fateful day for me. Eyes, as it turned out, hurt once and for all.

An incurable illness spoiled my whole life in many ways, did not allow me to acquire knowledge (to be formed) to the extent and degree to which I wanted to master it by entering the Literary Institute, and did not allow me to write much of what I could and should have written.

Sergei Pavlovich, when we got to know him better, and he found out about my illness, he tried his best to help. Using all his connections, he arranged for me consultations at the Fedorov clinic (then not as well known as it is now), then at the Helmholtz Institute (through the daughter of Vitaly Banka, who worked there, with the famous eye doctors Rosenblum and Kaltsenson. I myself also looked for all conceivable and unthinkable ways to cure.In Moscow, he entered the First City Eye Hospital, a research institute led by Academician Krasnov (accidentally found there one of his acquaintances back in Kaliningrad. He received the Lenin Komsomol Prize as one of the developers of laser eye treatment), after that, in Voronezh, he was examined by all the best local eye doctors - he even flew to the famous old herbalist in Tyumen, and at home, in the village, he tried to be healed by a village "whisperer" by conspiracy and prayer. But everything turned out to be in vain. to this day, every line I write, read, and print comes to me with great difficulty.

On that fateful evening in 1968, I, of course, did not want to think about all the consequences of my so unexpected illness. The main thing is to pass the exam in history. I looked longingly at the pages that had not yet been read and understood well that even if I spent the whole night over them, I would still not completely overcome them. And then I suddenly remembered that two weeks ago my army comrade, Muscovite Volodya Krylov, passed the entrance exams for the art department of VGIK and was already enrolled as a student. articles that were published in various metropolitan and regional publications, including the Voronezh magazine "Rise", Honored Artist of the Russian Federation). Volodya is a thorough man, well organized in all matters, and, according to my assumptions, he could well have kept notes-cheat sheets on history (how can a poor applicant pass the exam without them?!). I called Volodya, and to my happiness, his cheat sheets did indeed survive. I rushed to Volodya, already a student, a future film artist on Kutuzovsky Prospekt.

But when Volodya handed over all his notes to me, I became as disheartened as when I looked at an unfinished textbook. There were about three dozen of them, and only one analysis and systematization of the leaflets written in Volodin's not very legible handwriting had to be spent half the night.

I didn’t do any of this, and I couldn’t physically do it anymore - it was very bad with my eyes. After talking a little more with Shirikov on the most tricky historical topics, I decided to surrender to the will of chance, God's will - what will be, will be.

In the morning, however, I came to my senses and somehow sorted Volodya Krylov's notes. And indeed, not without the will of God, not without God's providence, he sorted them where they were right. He folded a rather impressive pile into his left pocket, and put one, which dealt with the Crimean War of 1853-1856, separately in his right pocket.

And it had to happen that the second question on the exam came across to me was the Crimean War. The first was the question of the Soviet Constitution of 1918. I knew the answer to it by heart and once again thanked myself that I studied the history of the KSS with diligence at the Pedagogical Institute.

In general terms, I also knew the answer to the second question: I could describe in sufficient detail all the same ill-fated socio-economic and political reasons that led to the war, but with an explanation of the hostilities (defense of Sevastopol, Balaklava, etc.) I would certainly get confused . Volodin's crib saved me. I secretly pulled it out, adjusted it on my knee, spied something and fearlessly went to take an exam to Mikhail Alexandrovich Vodolagin, head of the department of Marxism-Leninism of the Literary Institute, a man in many respects orthodox, about whom, however, it was said that, despite all this orthodoxy of his changes his beliefs exactly one day before the change of power at the top takes place ”I could be convinced of the validity of these suspicions more than once, often communicating with Mikhail Alexandrovich both at lectures and at meetings of the party bureau, where I was elected on the second or on third year.

So it was difficult, with such obstacles and complications, I went to meet Sergei Pavlovich Zalygin, then, of course, not yet imagining that I would be closely acquainted with him for more than thirty years, that he, following Yevgeny Nosov, would accept in my literary and worldly fate such an active and interested participation. My relations with Sergei Pavlovich, of course, will be completely different than with Yevgeny Ivanovich Nosov. Yevgeny Ivanovich is an indefatigable, open, tempestuous person, and in his simplicity could say something impartial under a hot hand. But that's what friendship is for, that's what kindred spirits are for. Nosov was a folk writer who absorbed all the moral laws, rules and customs of people's life and never betrayed them. Zalygin is a person and a writer of a completely different order. He was brought up not so much in the midst of folk life as in a learned environment and, according to my suspicions (maybe incorrect) was first of all a scientist, and then a writer. He knew how to keep his distance, not once in thirty years of communication did he call me “you”. And all on “You”, at first Ivan, and later Ivan Ivanovich” In the same way, strictly, without the slightest hint of familiarity, so common in the writing environment, he behaved with many other writers whom he patronized and whose talent is highly appreciated: Viktor Astafiev, Vasily Shukshin, Vasily Belov, Valentin Rasputin, Vladimir Krupin, Vladimir Lichutin, Boris Ekimov, Vladimir Kostrov. I adopted this manner from him and I try to behave with young writers just like that, in the Zalygin style - strictly, but kindly. But, of course, he adopted a lot from Evgeny Nosov. Yes, and you can’t get your own character anywhere, you can’t overpower what is given to you by nature, you live with it.

After enrolling in the Literary Institute, I went to Kursk for a few days, reported my successes to Yevgeny Ivanovich Nosov, said goodbye to the Kursk Pedagogical Institute forever, lamented the long separation from my future wife, who had to finish her studies as an art graph for another three years. Then, in exactly the same way, for just a few days he looked home, to his native Zaimishche, delighted and saddened his mother by entering a new, now Moscow institute. She was really happy about my admission to such an unusual institute, because she knew about my addictions to writing. But I also saw something else: she was already quite tired from my shuffling from one side to the other. By that time, my mother, with her weak widow's strength, had taught my older sister Tasya at the medical institute, taught me for two years, sending frequent food parcels (for our years of study with my sister, she sent them, probably several hundred) and fifty rubles of money - a monthly increase in scholarships. At the Pedagogical Institute, my mother had only two winters left to finish my education, and it would have been possible already, if not to count on reciprocal help from my side, then at least for a respite in all these endless sendings and loans. Now the mother had to start all over again with me and bring her overgrown student to mind-reason. She did it - she died at only fifty-five years old and just in those days when I was accepted and accepted into the Writers' Union, in the now incredibly distant 1976.

I arrived in Moscow on the very last days of August. Volodya Sharikov and I settled in the 151st room of the Literary Institute dormitory, began to prepare for classes and especially, of course, for seminar meetings with Sergei Pavlovich Zalygin, for the sake of which, in fact, we entered the Literary Institute.

I remember very well, in the smallest details, this first seminar at the Institute of Literature. It was conducted, however, by Sergei Pavlovich not alone, but together with the then young essayist and guardian of the theme of the working class in literature, Boris Alekseevich Anashenkov. We did not pay due attention to Anashenkov: none of us knew his name, and, to be honest, it was of little importance. Boris Anashenkov, as far as I know, was invited to the Literary Institute to lead a seminar on essay writers (journalism was considered in those years perhaps the main genre of our literature), but this seminar did not take place for some reason, and Zalygin took Anashenkov as his assistant, although, it seems that he did not trust his literary predilections and his literary tastes in everything, which we witnessed more than once at the seminars. But Zalygin needed an assistant, because he often went on business trips both around the Union and abroad. Seminars in such cases would remain ownerless, classes would be canceled, rescheduled, but still held with an assistant. True, they did not arouse much enthusiasm in us.

The people for the first memorable seminar for all of us gathered people, probably under thirty, and then, look, more. I don’t know how it is now, but then full-time students and part-time Muscovites were united in one seminar. There were not so many of us

Gastan Agnaev from North Ossetia

Georgy Bazhenov from Sverdlovsk

Rasam Gadzhiev from Dagestan

Svetlana Danilenko from Pskov

Ivan Eveeenko from Chernigov-Kursk

Nikolai Isaev from Leningrad

Yuri Mikhaltsev from Moscow

Nikola Radev from Bulgaria

Svilen Kapsyzov from Bulgaria

Boris Rolnik from Donetsk

Svyatoslav Rybas from Donetsk

Valery Roschenko from the Far East

Vladimir Shirikov from Vologda.

There were two more people whom Zalygin expelled from the very first year due to low creative abilities: Abulfat Mamedov from Azerbaijan, a tall, languid guy who wore black and white gypsy-looking shoes, and an inconspicuous and even some downtrodden girl from Yakutia named Dusya (I, unfortunately, forgot her last name).

But the Muscovites-correspondence typed apparently-invisibly. I remember some of their names and surnames, did they sound at roll call in some indissoluble unity, as if they belonged to one person?

Gurfinkel,

Trukhachev,

Trushkin, etc.

After the second year, almost all of these Muscovite correspondence students from the Zalygin seminar will run away to the seminar of Nikolai Tomashevsky and there they will successfully graduate from the Literary Institute. Of these, only one name will appear in the literature, the humorist Sergei Trushkin, now an indispensable participant in all humorous programs, all "Full House" on television.

In our Zamyginsky seminar, Yaroslav Shipov will remain and forever gain a foothold among Muscovites-correspondents. Now he is widely known both as a great writer and as an Orthodox priest Father Yaroslav.

Sergei Pavlovich began the seminar by introducing each of us by name. We rose from the tables in turn, told our not-so-long biographies, expounded, as best we could, our literary predilections.

After listening attentively to all of us and making some notes in an ordinary student notebook, Sergei Pavlovich, not in great detail, but very thoroughly, spoke about himself, about his literary views and interests. The range of these interests of his was wide and largely unexpected for us (at least for me). Closest to him were village writers: Astafiev, Belov, Shukshin, Nosov, Abramov and many others from this series. Astafiev, Belova and Shukshina, Sergey Pavlovich, as a senior in age, literary experience and organizational capabilities, really even then, as it were, took care of, took the most interested part in their difficult destinies.

But, on the other hand, such writers and poets as Vasily Aksenov, Anatoly Gladilin, Anatoly Kuznetsov, Andrey Bitov, Andrey Voznesensky, Bella Akhmadulina, Georgy Vladimov were very interesting to him.

Having finished this short mutually interested acquaintance, Sergei Pavlovich thought for a minute, and then suddenly said:

Here’s what (after almost every one of his closing words at seminars, he will begin exactly like this: “here’s what”), I won’t be able to teach you literature, writing, they learn this on their own, but we will try to push, expand your worldview. This is the whole point of our work.

The beginning was somewhat unusual, but we accepted it: to expand the worldview in such a way, although we ambitiously dreamed of quickly studying at the Literary Institute as a writer. With the worldview, as it seemed to us, everything was in order,

In a year, we will part with half of you: someone will not like me, someone will not like me.

We were simply speechless from such speeches and from such a future, which Sergei Pavlovich promised us. After all, we all entered the Literary Institute with such difficulty (the creative competition alone was about sixty people per place), and suddenly, in just a year, part with the dream of a lifetime, with the intention and desire to become a writer. No, we didn’t expect this and couldn’t come to terms with it, which after that we argued heatedly more than once both in the hostel and within the walls of the Literary Institute on Tverskoy Boulevard, 25.

And it seemed to Sergei Pavlovich that even these frightening words at that first seminar were not enough. And he, finishing classes, warned us:

You are adults, you knew where you were going, and if you start behaving in an inappropriate way at the institute and in the hostel, then I will not defend you anywhere. Not a pleasant promise either...

This concludes our orientation seminar. Sergei Pavlovich announced that next we would discuss Chekhov's work, asked to re-read some of his most famous stories and said goodbye. He left for the department of creativity, and we, completely dejected, discouraged, went to the hostel, not really understanding why in the next lesson we should discuss the stories of Chekhov, and not one of the seminarians.

Many years later, Sergei Pavlovich once told Georgy Bazhenov and me why then, at the first seminar, he behaved so exorbitantly strict and harsh. In his main specialty, Sergei Pavlovich was a hydrological engineer, a candidate of technical sciences (he also wrote a doctoral dissertation, but did not defend it, completely surrendering to literature), he taught sixteen lats at the Polytechnic Institute, was, it seems, even the head of the department. He had considerable experience working with students, and he decided not to change it. It was just that at the Literary Institute the students were engaged in a different matter, literature, and not hydrology, but in all other respects they remained exactly the same students, and Sergei Pavlovich did not consider it possible to behave about them in any other way. Now I think he did the right thing then. Familiarity with students, seminars at home over a cup of tea, and sometimes something stronger, and similar liberties that other teachers of the Literary Institute often practiced, as a rule, did not lead to anything good.

In general, Sergey Pavlovich got into the teaching staff of the Literary Institute by accident, the reason for this was Alexander Tvardovsky, with whom Zalygin became close friends after the publication of the story “On the Irtysh” in Novy Mir. Sergey Pavlovich told us more than once a rather dramatic story with the publication of this story. He sent it to almost all the then thick literary and art magazines, but received a refusal from everywhere: none of the chief editors dared to publish such a bold story for those times, where the issues of collectivization and dekulakization were posed sharply and contradictory, destroying in everything the already firmly established view of this period of our historical development. There was only one "New World". Sergei Pavlovich sent the story there without any particular hope of publication. But just two weeks later, a telegram came to him from Tvardovsky with the following content: “We are publishing the story. The name "Above the Irtysh" is changed to "On the Irtysh". At least, Sergei Pavlovich told me the story of the publication of the story "On the Irtysh" in this interpretation. After this publication, warm, friendly relations were established between Tvardovsky and Zalygin, which lasted until the death of Alexander Trifonovich.

When, in 1967, the novel “Salty Pad” by Sergei Zalygin was published in Novy Mir, for which he would be awarded the USSR State Prize in 1968, Tvardovsky would tell him:

There is nothing more for you, Sergey Pavlovich, to do in Novosibirsk, it's time to move to Moscow.

But in those days, moving to Moscow, even with the help of Tvardovsky, a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, was not so easy and simple. Some form of formality was needed. The Literary Institute became such a hook. Tvardovsky, apparently, agreed with the rector of the Literary Institute, Vladimir Fedorovich Pimenov, and he invited Zalygin to lead a prose seminar.

So happily our paths converged with Sergei Pavlovich.

This move from Novosibirsk to Moscow was not easy for him. For three years Sergei Pavlovich toiled in the capital without an apartment: he was temporarily registered in the dormitory of the Literary Institute, and lived either in the House of Creativity in Peredelkino, or rented a room there near the railway station. Georgy Markov secured an apartment for him, with whom they were well acquainted back in Siberia (Markov, as far as I know, together with Vladimir Lidin gave Zalygin a recommendation to join the Writers' Union), in a house on Leninsky Prospekt, where many famous scientists lived. I have been in this house several times since.

It was no coincidence that we began to discuss the work of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov at the seminars of Sergei Zalygin. He had just completed his essay on Chekhov, which he called "My Poet", and now he wanted to test it on such picky readers.

On the very eve of the discussion, we had one funny incident. Gradually, it grew into a literary anecdote, and I happened to hear it in Voronezh, many years later.

All the same Abulfat Mammadov, who did not particularly bother with his studies, but bought a button accordion and learned some oriental melody on it early in the morning, bringing Volodya Shirikov and me to white heat, since he lived in the next room, asked Rasim Gadzhiev:

Who are we discussing at the seminar tomorrow?

Chekhov, - answered Rasim.

Is he studying with us? Abulfat asked innocently.

All of us in those years were not God knows how strong in literature, but still we knew something about Chekhov, but for Abulfat he turned out to be a pure revelation. Therefore, it is probably quite fair that Abulfat and I parted ways a year later, although it is a pity - maybe he knew such names and such revelations from Eastern literature that we had never heard of. Everything is relative in this world.

Recently I happened to read in the memoirs of Mikhail Petrovich Lobanov a rather dismissive review of Sergei Zalygin's essay "My Poet". Say, when this essay appeared in print, then at the Institute of World Literature. Gorky, many employees laughed at him. I will allow myself to disagree with such a statement, which, apparently, is dictated by the disagreements that arose between two major Russian writers in the 90s of the last century, when they ended up in different literary camps and Unions. But in the 60s and 70s, it seems to me, they stood close to each other in their literary preferences, otherwise they would not have converged on the pages of the same magazine, Nashe Sovremennik, which, to a certain extent, became the heir to the New world”, where Sergey Zalygin mainly published, and “Young Guard”, where one of the leading authors was Mikhail Lobanov.

Moreover, in the heat of some of his belated resentments against Zalygin, Mikhail Petrovich did not bother to reopen the essay "My Poet", otherwise he would have read there in the author's preface with what intentions he undertook work on Chekhov. Zalygin warned the reader:

“I did not set the task of writing a literary criticism, and even more so a bibliographic work.

He did not consider or evaluate the views on Chekhov's work. I just wanted to offer my reading of Chekhov's works.

It seems that every writer has such a right. It is easy for a professor burdened with academic degrees and titles to be mockingly indulgent towards these attempts, but it is much more difficult to be thoughtful and inquisitive.

I am closer to the assessment given by Sergei Zalygin's essay "My Poet" by the late critic Igor Detkov:

"My Poet" is a book written on top of everything that has been said about Chekhov before. Zalygin analyzes rather than reconstructs the whole: personality, lifestyle and behavior, the world of the artist, the meaning of his presence and participation in life. Zalygin writes about Chekhov, about loneliness, the limits of talent and the norm in art and life, about tact, about the coordinates of human existence, and all this, in addition to the “definition” of Chekhov, includes the “definition” of one’s own moral and aesthetic choice. Following the author, the reader involuntarily does the same work: there is, as it were, a refinement of the coordinates of our existence ... "

According to Zalygin, shortly before his death, K.I. Chukovsky highly appreciated his essay on Chekhov.

But all these disputes and conflicting views on Zalygin's essay "My Poet" will be much later, and then, in the fall of 1968, we were the first readers and first connoisseurs of "My Poet".

Already at the first seminar, I must admit, I was seriously shy. My Moscow classmates from Trushkin, Trukhachev, and Gurfinkel kept pouring out the names of Kafka, Proust, Joyce, and other Western writers little known to me at the time. Willy-nilly, a treacherous chill settled in my soul. “Well,” I thought to myself, “you got caught, Vanya!”

Only Georgy Bazhenov could resist the intellectual pressure of the Muscovites among us, full-time students. Despite his youth (he was then only 22 years old), Hera knew Kafka, and Proust, and Joyce, read them not only in Russian, but also in English, was comprehensively educated, besides, he had a rare independent mind and such independent, non-bookish judgment on any subject. He basically fought with fans of Kafka and Joyce. I prudently kept quiet, gained my mind.

Sergei Pavlovich listened to the debaters attentively and with interest, made notes in his student's notebook, and at the end always concluded the seminar with an unexpected judgment, invariably beginning his speech with the words that have already become familiar to us: "Here's the thing."

The Zalygin seminar was often attended by students from other parallel seminars of prose, poetry, and criticism. His name was well-known then, his authority was high and unshakable. At first, Sergei Pavlovich let everyone into the seminar, including young Moscow writers who were still dreaming of the Literary Institute, who were brought with them by their more successful friends, correspondence students, but then he began to treat the “newcomers” more harshly. At the seminars, they often raised a real bazaar, entered into a skirmish with us, legal seminarians, and with Sergei Pavlovich himself. He was forced to deprive them of their words, quite sharply stopped their attacks:

Let our people say.

And soon he rarely allowed outsiders to attend classes. It seems to me that Sergei Pavlovich acted then quite correctly. After all, he undertook to conduct a seminar at the Literary Institute not for the sake of empty literary (and often near-literary) disputes, but in order to prepare young children for serious literary, writing work, in whom he saw a spark of talent. In the same way, he most recently trained at the Polytechnic Institute of Hydrologists, a specialist in precise, applied knowledge. Obviously, noisy disputes happened there too, but without the boundless indefatigable freemen: science requires concrete evidence based on theory and practice. Literature, of course, is a different matter in many respects, but it also has its own laws and its own categories. And Zalygin also tried to make us as serious experts in the field of belles-lettres as possible, at least to expand our worldview, to shake our thinking.

Starting the seminars with a discussion of his own work, Sergei Pavlovich, in my opinion, acted subtly and far-sightedly in a pedagogical sense. He was not afraid of harsh judgments on our part about a work about his beloved writer Anton Pavlovich Chekhov, which was very dear to him (there were plenty of these harsh and even impartial judgments), by his own example he showed how to treat criticism, how to conduct literary polemics, mutually respecting and appreciating each other's opinions. Later, he once confessed to me that at first he was very afraid that his seminarians, who think themselves one more talented than the other, would treat each other arrogantly, disrespectfully. Sergei Pavlovich very sharply (albeit tactfully) stopped even the smallest shoots and rudiments of an unfriendly, jealously envious relationship between us. And, it seems, he achieved his goal. With all the difference in characters and varying degrees of literary talents, we gradually rallied into a friendly creative team, which proudly bore the title of "Zalygin seminar".

After looking closely at each other during the discussions of My Poet, we were looking forward to when we would start discussing our own compositions at the seminars. Indeed, without such discussions, in essence, we still did not know who of us was worth what.

My short stories were among the first to be discussed. So for some reason Sergei Pavlovich decided. Perhaps it seemed to him that on these not quite traditional stories it would be possible to check how traditionally and unconventionally his wards think, how capable she is of perceiving literature of different directions.

Now I do not remember for certain how this first discussion for me at the Literary Institute went. But I well remembered how, at the end of the discussion, Sergei Pavlovich, in his concluding speech, dropped a phrase that was flattering to me:

The ability to metaphor, to parable, as well as to hyperbole, indicates the presence of talent.

One could, of course, be seduced by this praise, become proud like a youth. But, fortunately, this did not happen to me. After all, I passed the first literary baptisms in Kursk with Yevgeny Ivanovich Nosov, and he did not indulge his students with praises. After reading the story, he could say with all frankness: “I don’t see work!”

I also remember the speech at the discussion of my stories by Gera Bazhenov. He spoke laconicly, but logically and consistently (after Georgy Bazhenov will prove himself as a subtle, insightful critic, he will write many critical articles, including an article about Zalygin, timed to coincide with his seventieth birthday, which will be published in the Sever magazine), immediately catching , which is the main thing in my short stories of the fate of the heroes, the clash of characters, and the clash is not so much external as deeply internal.

After this discussion, Bazhenov and I became close friends and were inseparable friends for almost thirty years, going through many difficulties shoulder to shoulder both while studying at the Literary Institute and later, already in the life of a writer. We parted in the late 90s for various reasons, both purely worldly and ideological.

Little by little we came to a discussion of the stories and short stories of our fellow students in Moscow, Trushkin, Trukhachev, Gurfinkel, and so on. And then I perked up. Of course, they knew Kafka, Joyce and Proust better than I did, but as for the knowledge of living life (whether urban or rural), they had perceptibly noticeable gaps. In any case, this knowledge was not revealed in the stories under discussion. All the compositions of the guys were somehow forced, strained, I did not remember a single one of them. Only Sergei Trushkin presented humorous miniatures for discussion. But even then I believed, and still believe, that the satirical stories of our other comedian, Nikolai Isaev, were deeper in their essence and artistically more perfect. After graduating from the institute, Nikolai Isaev, unfortunately, fortunately, but due to his too melancholy Petersburg character, did not join any "sold out", "rooms of laughter", "crooked mirrors", "around and around laughter", remained independent loner satirist. And this in the corporate environment of comedians, it seems, is not forgiven.

Sometimes at seminars Sergei Pavlovich gave us so-called "etudes". This invention, it seems, was Anashenkov's, but Sergei Pavlovich accepted it, probably believing that it would be useful for students of the Literary Institute, as well as students of hydrology, to do laboratory work from time to time.

The labs looked like this. Sergei Pavlovich came to the next seminar and suddenly, smiling a little secretly, he told us: - Today we are writing a study.

and set the topic. I still remember some of these topics: "Two tracks",

"In the train", "On the grave of the waiter."

The "etudes" did not arouse special enthusiasm in us. There was something scholastic about them, but we all considered ourselves already seriously committed to literature and wanted to study it, too, seriously, not in a student way. Later, Sergei Pavlovich himself admitted that this notion of Anashenkov was not the best.

But then we had nowhere to go, we had to grind out the ill-fated “etudes” for two, or even two and a half hours. I often went to the trick and instead of a prose essay, at the end of the seminar I submitted poems to the judgment of Sergei Pavlovich and my fellow students, it happened, and in just four lines, something like an epigram. After classes, we discussed the “etudes” and mutually gave marks to each other. Everything is also somehow school-like, bursatsky.

Much more interesting and useful were meetings with well-known writers of those years, whom Sergei Pavlovich invited to the seminar. I especially remember the meeting with Yuri Trifonov and Georgy Semenov. Yuri Trifonov then just wrote his famous urban stories: "Preliminary results", "Exchange" and others. We discussed one of these stories. Sergei Pavlovich instructed Yura Mikhaltsev to make a report. It seems that even from the very first seminars he noticed that Yura was more prone to criticism than to prose. There was good reason for this observation. Yura was, if I am not mistaken, the adopted grandson of Leonid Sobolev and entered the Literary Institute, of course, not without the influence of his name, almost immediately after school. True, he never boasted of his famous kinship, he behaved somehow emphatically quietly and imperceptibly. With stories, things went poorly with him, but with a critical analysis of modern literature, it was noticeably better, after all, good literary preparation and erudition had an effect. Sergei Pavlovich, after a report on the stories of Yuri Trifonov, several times entrusted him with critical analyzes at seminars, and at the end of the second year, following the results of creative re-certification, he advised him to go to a criticism seminar. Yura obeyed Sergei Pavlovich - he moved on and, I think, he did the right thing. After graduating from the institute, he worked in the Ogonyok magazine when A. Sofronov was still there, at one time he even was a member of the editorial board there. His critical skills in the editorial office undoubtedly came in handy. I remember a good article by Yurina about his adopted grandfather Leonid Sobolev. Perhaps this was one of the last works about the work of the author of "Major Repair", which is now undeservedly forgotten.

Yuri Trifonov told us in detail about his entry into literature and especially about his acquaintance and relationship with A.T. Tvardovsky. There was one instructive episode in his story, which it was impossible not to remember. At the age of twenty-five, Trifonov wrote his first novel, Students. It was published in the Novy Mir and in 1951 was awarded the Stalin Prize (in our time, the Stalin Prizes are shamefully called State Prizes - also a considerable sign). Inspired by such an unexpected success, young Trifonov came to Tvardovsky and began to ask him for a business trip to collect material for a new novel he had conceived. Tvardovsky looked attentively at the excessively proud author and suddenly said:

It would be nice to have a story...

Yuri Trifonov remembered this lesson for the rest of his life. He did not write any new novel at that time, but really set to work on stories, gaining literary experience, "writing out" in them and getting rid of his youthful pride, He lived to the end or did not live out - it's not for me to judge. But at a meeting that is memorable for us, he spoke about his first novel with some condescension.

The meeting with Georgy Semyonov was quite different. So he was a completely different person. In everything open, sincere and almost childishly shy, shy. Despite his youth (he was not yet forty years old), Georgy Semenov deservedly became famous as one of the few representatives of the generation called by ornate critics: "a city man in nature." This generation was undoubtedly headed by Yuri Kazakov, the closest friend of Georgy Semenov both in literature, in life, and in his passion for travel, for nature. This generation was indeed small. But what! Yuri Kazakov, Georgy Semenov, Gleb Goryshinin, Viktor Konetsky. Today, alas, none of them are alive anymore. Yuri Kazakov's generation (that's how it can be characterized) occupied an intermediate position between the generation of "confessional prose" and the "villagers". And so it will remain in the history of our literature. All its representatives are purely urban people. (Georgy Semyonov said that in his family, in the pedigree, even in the most distant times, there was no grandfather-great-grandfather who was not a Muscovite), but passionately in love with nature, maybe just the opposite - they were so tired of the asphalt-stone city life. With no social upheavals, like, say, "villagers" "-children of the village, the land, they did not write and could not write. They were more interested in nature and the relationship of man with nature. To a certain extent, they are all successors and heirs of K. Paustovsky , M. Prishvin, I. Sokolov-Mikitov and other writers of this series.

Georgy Semyonov was masculinely handsome: tall, stately, he really felt the urban breed, verified for centuries, even groomed. He desperately loved women, and was recklessly loved by them in return, about which in a merry moment he could not only boast, but with a generous smile, especially if he drank a glass. And he liked to drink (what kind of hunter and traveler does not like to drink?!). But all these legends about his Don Juanism, I think, were too exaggerated, because the name of his wife, Elena, did not leave the lips of Georgy Vitalievich. At every word, he repeated: "Lenka and I." In the writing community, as I was later told, they even jokingly began to call him Myslenko, which means: "Lenka and I." He was not offended by this nickname, treated him easily, with a smile.

It is extremely unfortunate that Georgy Semenov passed away so early. He was barely sixty. In addition, for the last two or three years he had been seriously ill and did not write anything anymore, he could not write.

But in the late sixties, Georgy Semenov was in the prime of his strength and talent. In the magazine "Znamya" just then his story "By winter, bypassing autumn" was published. We discussed it at the seminar.

Georgy Vitalievich entered the audience, as it seemed to me, not without timidity, in extreme cases, not without shyness. He sat down at the table opposite our belligerent audience, put the pipe next to him, which he then smoked.

Sergei Pavlovich introduced him to us and, as it were, went into the shadows, giving Georgy Vitalievich the opportunity to communicate with the audience one on one, without intermediaries. Georgy Vitalyevich was silent for a while, turned the pipe in his hands, as if considering whether to light it or not, but he did not light it and began, rather out of necessity than desire, to talk about himself, about his primordially Moscow ancestry, about how in childhood survived the war for years. The mention of this was more than opportune, since in the story that we were to discuss, it was just about the war. Preparing for the seminar, we just found out that Georgy Semenov studied at our Literary Institute (everyone probably had a sweet heart skip a beat - maybe I will have the same happy literary fate and fame?) But we didn’t know at all that before the Literary Institute He graduated from the School of Industrial Art with a degree in art modeling. After college, Georgy Vitalievich worked for several years somewhere in Siberia (I think in Angarsk) in construction. At that time, stucco ceilings, pilasters and capitals were still in fashion, and he was engaged in the construction of them. Georgy Vitalievich spoke about his first specialty with great enthusiasm and knowledge of the matter, it was felt that he loved it no less than literature. In the end, however, he regretted that now this specialty is almost forgotten, the construction went hollow, wretchedly primitive, no one makes stucco ceilings and cornices. So he went into literature at the right time. This specialty, lost and no longer in demand by anyone, seems to have haunted Georgy Semenov for many years. And he wrote a beautiful story about her, "Handmade".

Before proceeding to the discussion of the story “To Winter, Bypassing Autumn”, we could not help but ask Georgy Semenov a question about his friendship with Yuri Kazakov. Most of all, we were interested in the question why Kazakov has not written anything for a long time? Georgy Vitalievich again was silent for a while, and then with a smile, but at the same time with anxiety for his friend, he said:

I asked him about it. He says: “Old man, maybe everything that I was supposed to write, I have already written.”

Maybe so, the writer's paths are inscrutable, and it would not hurt us to know about it at the very beginning of creative daring. But still, talking about his confidential conversation about Yuri Kazakov, Georgy Vitalievich unconcealedly harbored the hope that he would write many more wonderful stories. And he turned out to be right. A few years later, Yuri Kazakov actually wrote two stories: “In a dream you wept bitterly” and “Candle”. Here, willy-nilly, you will think: maybe it’s true that the writer needs to be silent for a whole decade in order to write such stories later.

After this short acquaintance with Georgy Semyonov and his biased interrogation, we finally began to discuss the story "Towards Winter, Bypassing Autumn." Georgy Vitalievich got it from us on the very first day. In many respects, perhaps, that is fair. This story can hardly be attributed to the best creative achievements of Georgy Semenov. In general, it seems to me that he is interesting (and more accomplished) precisely in stories, and not in stories, even such as "The Horse in the Fog" or "Urban Landscape". Despite the noisy success in publications, they are now almost forgotten. But the stories of Georgy Semenov, of course, will have a long life. Sooner or later they will return to our yearning for fine literature, for the innermost human feelings of literature.

Our George Vitalyevich endured the pogrom with dignity and enviable patience. In his defense, he spoke little, listened more, and smiled coyly, bowing low to the table his large head, which was then crowned with curly hair, not even a single gray hair.

Sergey Pavlovich reconciled us with him. He also made several, again, completely unexpected remarks about the story, and then suddenly, seeing our irreconcilably belligerent attitude towards it, he defended Georgy Vitalyevich:

I believe the writer, Georgy Semenov.

We also believed him. Georgy Vitalyevich, it seems, felt this, did not hold a grudge against us (he himself was a student of the Literary Institute only ten years ago - he knows what his seminars and his seminarians mean), said a few words in conclusion and almost saying goodbye to us, he suggested:

I am now a member of the editorial board of the Smena magazine. Bring stories, I'll try to help with the publication.

And recklessly left us his home number.

I don’t know about my other classmates, but I used this phone number. Having gathered impudence, one day he called Georgy Vitalyevich at twelve in the morning. My wife picked up the phone, listened to my excited babble and said in a slightly muffled voice:

He's sleeping. Call in the evening.

To be honest, I was a little surprised by this answer. According to my village concepts, it would be in no way supposed to sleep at twelve o'clock in the afternoon - after all, the most working, fertile hours in any business, even arable, even literary. I hung up in bewilderment and even with resentment, deciding that the wife of Georgy Vitalyevich (Elena, Lenka) in such a cunning way refuses to talk to me with him, protects her husband from annoying petitioners.

But then I didn’t have to be stubborn. By evening, having somehow survived my offense, I again called Georgy Vitalievich. This time he picked up the phone himself and, chuckling, explained his morning-day dream:

After all, I write at night, and in the morning I sleep, I fill up.

In fact, it was only then that I learned that there are two kinds of writers: "larks" and "owls." Some write in the morning, others at night. Georgy Semenov was, if I may say so, a classic “owl”, he wrote only in the dead of night, waiting until absolute silence would come in the whole house, and on Moscow streets, and maybe in the whole world, and no one and nothing would be to interfere in communication with oneself, and even with God, without whose providence not a single Russian writer (even a true believer, even an inveterate atheist) will write a single word.