(29 December 1809 - 19 May 1898) - English statesman and writer. He was Prime Minister of Great Britain four times (December 1868 - February 1874, April 1880 - June 1885, February - August 1886, August 1892 - February 1894). 41st, 43rd, 45th and 47th Prime Minister of Great Britain.

Born in Liverpool into a family of Scottish origin. He was the fifth child of six children of Sir John Gladstone (1764-1851), a wealthy merchant, well educated and active in public life; in 1819-1827 he was a member of Parliament, and in 1846 he became a baronet. Mother Anna Mackenzie Robertson instilled in William a deep religious feeling and developed in him a love of poetry. From an early age he showed outstanding abilities, the development of which was greatly influenced by the influence of his parents.

Gladstone received his initial education at home, in 1821 he was placed at Eton School, where he remained until 1828, and then entered Oxford University, where he graduated in the spring of 1832. Mentally, he took everything he could from Eton and Oxford; hard work gave him extensive and versatile knowledge and aroused in him a keen interest in literature, especially classical literature. He took an active part in the debates of the Eton Society of Fellows (under the name The Literati) and in the publication of the Eton Miscellany, a periodical collection of the works of the students, being its energetic editor and its most active supplier of material, in the form of articles, translations and even satirical and humorous poems.

At 22, Gladstone is already a member of parliament from the Tory party, and soon enters the Conservative government. His political and economic views have evolved over time. A conservative guardian of the fundamentals early in his career, opposing the abolition of grain duties, Gladstone from the mid-40s. draws closer to supporters of free trade (free traders) and leans toward liberalism.

The changes taking place in society (the weakening of the position of landlords, the growth of the urban population, the increasing role of the middle strata, the strengthening of trade unionism and the political activity of the working masses) required a turn of society towards democratization. William Gladstone sensitively grasped the vector of this turn. He left the Conservatives and joined the Liberal ranks, and in 1865 became leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons.

The liberal doctrine included the following components: an economy based on private property and the market, a minimal role of the state (the idea of the state as a “night watchman”), constitutionalism and parliamentarism, personal freedom, freedom of speech, conscience, assembly, and finally, reforms as a method of gradual, moderate and purely legal changes in society to solve pressing problems.

His activities reflected the main positions of classical liberalism. The first Liberal government of William Gladstone was rightly called "reformist". At this time, a law was passed on the separation of the Anglican Church from the state in Ireland and the Land Act, which provided a number of guarantees to Irish tenant farmers. The 1870 education law was very relevant, introducing a system of public primary schools and compulsory education, which provided the opportunity for the children of workers to attend school. Religious qualifications in universities were abolished, and people of non-Anglican faiths could receive scholarships and degrees. A secret voting procedure was introduced for parliamentary elections. Trade unions received legal rights. These reforms contributed to the democratization of English society.

During the election campaign of 1879 - 1880, Gladstone for the first time used political technologies unprecedented for that time: delivering keynote speeches directly to voters. During a 2-week trip to the Midleton constituency, he spoke in front of tens of thousands of Englishmen, becoming a kind of “trend setter” for such political events.

William Gladstone also contributed significantly to the democratization of the British electoral system. Back in 1866, he introduced a bill on suffrage reform to parliament; the Conservatives then defeated it, accepting the reform when they came to power in 1867. But Gladstone introduced liberal amendments to the law, which significantly changed its character. As a result, qualified workers received the right to vote based on property qualifications. In 1884, after William Gladstone's third parliamentary reform, when this right was extended to small tenants and agricultural workers, the size of the electorate increased by 1.5 times.

Within the framework of the liberal system of views, W. Gladstone also considered the problems of the British Empire. He believed that the empire was a weakness for England; its strength was in guaranteeing equal rights to other peoples. Gladstone called for the empire to be given the character of self-governing nations with representative governments. In an effort to neutralize Irish resistance to British rule, Gladstone repeatedly tried to introduce into Parliament a Bill for Home Rule (autonomy) of Ireland within the British Empire. His last attempt to pass this bill led to a split in the Liberal Party, from which came supporters of preserving the union of England and Ireland (liberal unionists). Disagreements within the Liberal Party forced Gladstone to resign as prime minister in 1894.

The “Great Old Man,” as his contemporaries called him, died on May 19, 1898, but contradictions within the ranks of liberals were intensifying, which was a reflection of the deepening crisis of classical liberalism.

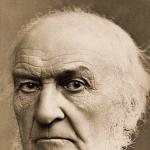

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: Here is my first principle of foreign policy: good government at home. My second principle of foreign policy is this—that it aims to be to preserve to the nations of the world—and especially, were it but for shame, when we recollect the sacred name we bear as Christians, especially to the Christian nations of the world-the blessings of peace. That is my second principle. Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 115.

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: Ireland, Ireland! That cloud in the west! That coming storm! That minister of God"s retribution upon cruel, inveterate, and but half-atoned injustice! Ireland forces upon us those great social and great religious questions— God grant that we may have the courage to look them in the face, and to work through them . Letter to his wife, Catherine Gladstone (12 October 1845), quoted in John Morley, The Life of Wiliam Ewart Gladstone: Volume I (London: Macmillan, 1903), p.

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: My fourth principle is that you should avoid needless and entangling engagements. You may boast about them, you may brag about them, you may say you are procuring consideration of the country. You may say that an Englishman may now hold up his head among the nations. But what does all this come to, gentlemen? It comes to this, that you are increasing your engagements without increasing your strength; and if you increase your engagements without increasing strength, you decrease strength, you abolish strength; you really reduce the empire and do not increase it. You render it less capable of performing its duties; you render it an inheritance less precious to hand on to future generations. Speech in West Calder, Scotland (27 November 1879), quoted in W. E. Gladstone, Midlothian Speeches 1879 (Leicester University Press, 1971), p. 116.

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: Economy is the first and great article (economy such as I understand it) in my financial creed. The controversy between direct and indirect taxation holds a minor, though important place. Letter to his brother Robertson of the Financial Reform Association at Liverpool (1859), as quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 241

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: All selfishness is the great curse of the human race, and when we have a real sympathy with other people less happy than ourselves that is a good sign of something like a beginning of deliverance from selfishness. Speech at Hawarden (28 May 1890), quoted in The Times (29 May 1890), p. 12.

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: A rational reaction against the irrational excesses and vagaries of skepticism may, I admit, readily degenerate into the rival folly of credulity. To be engaged in opposing wrong affords, under the conditions of our mental constitution, but a slender guarantee for being right. Homeric Synchronism: An Inquiry Into the Time and Place of Homer (1876), Introduction

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: I am certain, from experience, of the immense advantage of strict account-keeping in early life. It is just like learning the grammar then, which when once learned needs not be referred to afterwards. Letter to Mrs. Gladstone (14 January 1860), as quoted in Gladstone as Financier and Economist (1931) by F. W. Hirst, p. 242

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: I am delighted to see how many young boys and girls have come forward to obtain honorable marks of recognition on this occasion, - if any effectual good is to be done to them, it must be done by teaching and encouraging them and helping them to help themselves. All the people who pretend to take your own concerns out of your own hands and to do everything for you, I won"t say they are imposters; I won"t even say they are quacks; but I do say they are mistaken people. The only sound, healthy description of countenancing and assisting these institutions is that which teaches independence and self-exertion... When I say you should help yourselves - and I would encourage every man in every rank of life to rely upon self-help more than on assistance to be got from his neighbors - there is One who helps us all, and without whose help every effort of ours is in vain; and there is nothing that should tend more, and there is nothing that should tend more to make us see the benefit of God Almighty than to see the beauty as well as the usefulness of these flowers, these plants, and these fruits which He causes the earth to bring forth for our comfort and advantage. Speech to the Hawarden Amateur Horticultural Society (17 August 1876), as quoted in "Mr. Gladstone On Cottage Gardening", The Times (18 August 1876), p. 9

-William Ewart Gladstone

Context: The right hon. Gentleman quoted repeatedly this declaration... to keep out of Egypt it is necessary to put it down in the Soudan; and that is the task the right hon. Gentleman desires to saddle upon England. Now, I tell hon. Gentlemen this-that task means the reconquest of the Soudan. I put aside for the moment all questions of climate, of distance, of difficulties, of the enormous charges, and all the frightful loss of life. There is something worse than that involved in the plan of the right hon. Gentleman. It would be a war of conquest against a people struggling to be free. ["No, no!"] Yes; these are people struggling to be free, and they are struggling rightly to be free. Speech https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1884/may/12/vote-of-censure in the House of Commons (12 May 1884) during the Mahdist War.

Gladstone's early life

Gladstone William Ewart (Ewart) - famous English politician, born December 29, 1809, died May 19, 1898. His father, John Gladstone, a Scot by birth, a wealthy merchant who settled in Liverpool, was a Conservative member of the House of Commons in 1819 - 1827 . Young William Gladstone brought from home a rare work ethic, deep orthodox Anglican religiosity, and excellent home training. Already during his school years spent at Eton (1820 - 1827), he discovered at meetings of various school circles a strong oratorical talent, a versatile education, which was reflected in his numerous articles in the school (printed) magazine Eton Miscellaneous, published in 1827 under his editorship, and the ability to make a deep impression on everyone around you. Brought up under the influence of his father, as well as Canning, who was a close friend of his father, Gladstone, who at that time dreamed of either a spiritual career or a career as a political figure, was a definite conservative of the Canning shade. During his student years (1829 - 1832), which he spent at Oxford, Gladstone's conservatism remained unshaken; At meetings of student political societies, in which he took an active part, he made speeches against parliamentary reform, against the emancipation of slaves in the colonies, and for the patrimonial aristocracy. Having completed his university course with double honors in ancient languages and mathematics, he traveled around Italy. At the end of 1832, Gladstone was elected a member of the House of Commons in the Newark district, which was under the strong influence of the Duke of Newcastle, who patronized him.

William Gladstone's first speech in the House of Commons was devoted to the issue of slavery in the English colonies; While not unconditionally opposed to emancipation in principle, Gladstone found it untimely, insisted on the need to reward slave owners, and in particular defended his father against the charges brought against him for the mistreatment of slaves on his sugar plantations. This speech and, in general, Gladstone’s activities in the House of Commons so quickly promoted him in the ranks of the Tories that already in 1834 Robert Peel upon taking office as head of government, he was offered the post of first junior lord of the treasury, and a few months later assistant secretary of the colonial affairs. In 1835, William Gladstone retired along with the ministry of Robert Peel.

He devoted the following years, in addition to his current parliamentary studies, to an in-depth study of Homer, Dante and St. Augustine. The fruit of the study of theological literature was the books “The State in its Relations to the Church” (1838) and “The Principles of the Church, Evaluated by Their Results” (1840); in them Gladstone, based on the idea that the state, as such, “has a conscience,” argued for the need for the state to support and spread the Christian religion with the help of the state church. At this time, the future liberal Gladstone, according to Macaulay, was still “the rising hope of the stern and unyielding Tories” who followed Peel, horrifying him.

Gladstone's evolution from conservative to liberal

In 1841, R. Peel appointed Gladstone as associate president of the Bureau of Trade, and in 1843 as president; at the same time, William Gladstone became a member of the cabinet. During the execution of this position, a significant change took place in Gladstone, as well as in R. Peale. From extreme protectionists and in particular supporters of agrarian protectionism, they, gradually softening, became supporters of the abolition of the Corn Laws, and then free traders (adherents of free international trade). At this time, Gladstone carried out significant work on revising the customs tariff in the direction of its significant softening, and then spoke out for the repeal of the Corn Laws. However, the implementation of this last measure was no longer Gladstone’s business, since in February 1845 he resigned due to disagreement with R. Peel’s promise of a state subsidy for a Catholic educational institution in Ireland.

At the end of 1845, William Gladstone re-entered the cabinet as Colonial Secretary, but, having at the same time lost his seat in the House of Commons, did not consider it possible to appear before the voters of Newark, which was under the influence of the strictly conservative Duke of Newcastle. Only in 1847 was he re-elected as a member of the House of Commons from Oxford University. From 1846 to 1852, Gladstone was a prominent member of the opposition (the Peelite party) against the liberal ministry of Rossel; however, this opposition was far from conservative. Gladstone supported government measures such as the emancipation of the Jews; at the same time, he was a resolute opponent of the Lord's aggressive foreign policy Palmerston. In 1850, when Palmerston presented the Greek government with a demand for the payment of a significant remuneration to the English subject Pacifico, and motivated this by the need to achieve exceptional respect for the title of the English subject, so that he could proudly say everywhere, like an ancient Roman, “civis romanus sum” (“I am Roman citizen"), then Gladstone, in a remarkable speech, attacked this chauvinistic principle as unchristian.

William Gladstone spent 1850 – 1851 in Italy. Its political system and in particular the situation of prisoners in prisons in the Kingdom of Naples attracted his close attention, and he published the result of his study in the form of two letters to Lord Aberdeen “Two letters to the earl of Aberdeen on the state prosecutions of the Neapolitan government "; in these letters he severely castigated the despotism of the Neapolitan king, the arrests of the best citizens of the state without trial by administrative order, and especially the situation of prisoners in prisons. The letters made a deep impression throughout Europe and, although they could not have any immediate practical impact, they aroused special respect for Gladstone in Italy and brought him closer to many members of the " Young Italy" In 1852, the Earl of Derby, when forming a cabinet, offered Gladstone a place in it, but Gladstone refused; this refusal marked his final break with the Conservative Party. He even made severe criticism of the budget introduced by the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Disraeli.

Also in 1852, William Gladstone became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Liberal-Pilite coalition cabinet of Lord Aberdeen. The policy of the cabinet, despite the constant peace-loving statements of the Prime Minister himself and Gladstone, led to a war with Russia (see the Crimean War), for which Gladstone shared some responsibility, and which is in undoubted contradiction with the fundamental statements made by Gladstone in his dispute with Palmerston 1850. Since 1855, with the fall of the Aberdeen cabinet, Gladstone went into opposition. He protested against Chinese expedition of Lord Palmerston 1857, and contributed to Palmerston's defeat in the House of Commons on this issue. He remained in opposition during the administration of Derby (1858 - 1859). He took advantage of the comparative leisure to finish a large three-volume work on Homer, “Studies on Homer and the Homeric Epoch” (1858), to which Juventus mundi is adjacent in content. Gods and Men of the Homeric Age" (1869), "Homeric synchronism" (1876), "Landmarks of Homeric studies" (1890) and some minor works of Gladstone. They express Gladstone's conservative mindset in an original way, forcing him to treat all traditions with the deepest respect, but not preventing him from being a political reformer. In these works, Gladstone proves the historical authenticity of the Trojan War, the historical reality of the personality of the poet Homer, who glorified this war, and the unity of the poems of the Iliad and Odyssey. In his attitude to these facts, he is not only behind Wolf and other modern philologists, but even behind the New Alexandrian scientists, since he proves the authenticity of those poems that they had already suspected. Nevertheless, these works belong to remarkable studies. Incidentally, Gladstone put forward the theory (later rejected) that the ancient Greeks were not able to see the color blue.

In 1858, Gladstone accepted an assignment from the office of the Earl of Derby to travel to the Ionian Islands as an English commissioner to resolve the issue of the fate of these islands; Gladstone presented a report on the need to annex the islands in Greece, which was carried out by the next ministry of Lord Palmerston. In this ministry in 1859, Gladstone, despite significant disagreements between him and the prime minister, agreed to assume the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. The following years revealed a remarkable financier in William Gladstone. Under him, a long series of reforms were carried out in the financial system of England in a democratic direction; by the way, the paper tax was abolished, postal savings banks were introduced, the national debt was reduced, etc. In the field of foreign policy, Palmerston's ministry supported the South American States in their struggle with the North, and Gladstone defended this policy. In the elections of 1865, Gladstone was voted out of office at the Conservative University of Oxford, but received a parliamentary mandate for South Lancashire (which he had to replace in 1868 with a mandate for Greenwich, and in 1880 for Midlothian, whose representative he remained until the end of his parliamentary career in 1895).

William Gladstone, photo 1861

After Palmerston's death (1865), William Gladstone retained his post in Lord Rossel's cabinet and at the same time took the place of leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons. In 1866 he introduced a parliamentary reform bill into the House. The failure of the bill forced the ministry and Gladstone to resign. However, this bill was introduced in a modified form by the new Conservative cabinet of Derby-Disraeli, and Gladstone, having made some significant amendments to it, was a strong supporter of it.

Gladstone's first cabinet

After new elections (1868), which gave a significant majority to the Liberal Party, the Queen entrusted the composition of the cabinet to Gladstone. The first cabinet of William Gladstone (1868 - 1874), supported by a large majority in the House of Commons and strong support in public opinion, was rich in reform activities. In 1869, church and state were separated in Ireland. To justify himself from the charge of betrayal of the principles he set forth in his books on the relationship of church to state, Gladstone published “A chapter of autobiography” (Lond., 1869), in which he explained the motives that forced him to abandon his previous views. In 1870, the Irish Land Act was passed, which eased the situation of Irish tenants of plots from English landlords, and a law on compulsory education; in 1871, the sale of positions in the army was abolished; in 1872, a system of secret voting in parliamentary elections was introduced.

After the elections of 1874, which gave a significant majority to the Conservatives, Gladstone wanted to abandon political activity; The Marquis of Hartington was elected leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons in his place. In 1876, Gladstone published the famous pamphlet, immediately translated into all languages, “Bulgarian Horrors,” and organized a social movement against Turkey and the Turkophile policies of Disraeli’s conservative English government. Thanks to this movement, Disraeli-Beaconsfield was unable to actively intercede for Turkey during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878.

Gladstone's second cabinet

In 1880, new elections again gave a majority to the Liberal Party, and Gladstone formed his second cabinet (1880 - 1885). The main task that the cabinet had to resolve was the pacification of Ireland. In 1881, Gladstone carried out a new Irish Land Act, but since this measure did not calm the anti-English movement in the country, he decided to apply severe repressive measures to the Irish, the implementation of which was entrusted to the Secretary of Irish Affairs Forster. The Irish Land League (the main body of national resistance to the British) was closed; Habeas Corpus Act has been repealed in Ireland. The most prominent Irish figures, including Parnell, were arrested. Since this system also did not achieve its goal, Gladstone entered into negotiations with the arrested Parnell and concluded an agreement with him, on the basis of which Parnell and his comrades were released, Forster was replaced by Cavendish, and some conciliatory measures were promised. But Cavendish was killed by Irish patriots - Fenians immediately after arriving in Dublin, and this gave Gladstone a reason to once again take the path of harsh repressive measures. In 1882 Gladstone's cabinet bombed Alexandria and occupied Egypt, turning it into an English colony. In 1884, the same cabinet carried out a third parliamentary reform, which again increased the number of Englishmen who had the right to elect members of the chamber. In 1885 clash between England and Russia in Afghanistan almost led to war. Gladstone's acquiescence to Russia led to Gladstone's defeat in the House of Commons, which forced his resignation on June 9, 1885.

Gladstone's third cabinet

But after new elections in January 1886, William Gladstone formed his third cabinet, which included Chamberlain, Morley and other radicals, and did not include Gladstone's former allies, moderate liberals Goshen, Hartington and others. Chamberlain, however, soon left the government. The need to support the Irish party in the House forced Gladstone to agree with it, and he introduced the famous draft Home Rule(autonomy) for Ireland, from which begins an era in the history of the liberal party of England and in the life of Gladstone himself. A significant part of the liberal party, led by Hartington and Chamberlain, not wanting Irish autonomy, formed a new party liberal unionists. The rest of the liberals, led by Gladstone, have since received the name Gladstonians and have shown a clear attraction to radicalism. The Home Rule project led to the defeat of the ministry in the chamber, and after its dissolution, to defeat in the new parliamentary elections. Gladstone ceded the post of head of cabinet to the Marquis Salisbury and became the leader of the opposition.

William Gladstone devoted the next six years of relative leisure between his third and fourth cabinets to passionate agitation for Irish Home Rule, which he conducted in the House of Commons, at countless rallies and in the press; then - writing a series of articles on the situation in Italy, in which he severely condemned the policy Krispy, a number of works in the form of books (“The impregnable rock of Holy Scripture”, 1892) and many articles in various journals on theological issues, in which he, among other things, polemicized with Huxley And Darwinism and defended the truth of the Mosaic cosmogony. In 1890, when the court ordered a divorce between the O'Shea spouses and found the leader of the Irish movement Parnell guilty of adultery, Gladstone declared that it was impossible for him to continue relations with the Irish party while Parnell was its head, and thereby dealt the latter a severe blow. In 1891, At the annual meeting of the National Liberal Federation in Newcastle, William Gladstone made a remarkable speech in which he outlined a new program for the Liberal Party. This program included: Home Rule for Ireland, separation of church and state in Wales and Scotland, a new democratic reform of suffrage, adoption of the the state account for the costs of the electoral struggle, the introduction of salaries for members of parliament, the expansion of local self-government, the end of the occupation of Egypt. Reform of the House of Lords (which had the right to override the decisions of the House of Commons) was planned conditionally if “the lords do not show prudence.”

Gladstone shortly before his death

Gladstone's Fourth Cabinet

During the election of 1892, “the great old man” Gladstone, as he was called, showed remarkable activity, astonishing in his old age. The election gave a majority of 42 votes to the Gladstonians in alliance with the Irish, and Gladstone formed his fourth cabinet. This cabinet passed Home Rule for Ireland through the House of Commons, but it was defeated by the House of Lords, just like some of Gladstone's other liberal bills. This time Gladstone did not have enough energy to fight the lords, and he, suffering from eyes and some deafness, retired in March 1894; his place was taken by Earl Rosebery. Gladstone no longer spoke in the 1895 elections. After a long illness, he died in 1898 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, near the grave of his long-term political rival, Lord Beaconsfield (Disraeli).

Assessment of the personality and activities of William Gladstone

The whole life of William Gladstone represents one slow and steady process of transition from one camp to another, a transition that is far from being fully explained by a change in the political mood of those social classes of which Gladstone could be considered a representative. This political evolution of his is largely a matter of a personal change in his way of thinking. At the beginning of his career, Gladstone acted as a representative of the interests of the aristocratic class, then he defended the interests of the middle and petty industrial bourgeoisie, and at the end of his life he began to become intensely interested in social issues. Previously a strong opponent of legislative regulation of the working hours of adult men, he now wavered in his conviction. In connection with this change of heart, one important change took place in Gladstone. In his own words, neither Eton nor Oxford taught him to sufficiently respect a person’s personal freedom, the importance of which he later appreciated.

The constant work of remaking his own views resulted in some inconsistency, not only between the actions of William Gladstone in different eras, but also between his policies of the same period. Thus he discovered remarkable compliance towards Boers of South Africa, the war with which, inherited (1880) from the Beaconsfield cabinet, he stopped with England's voluntary recognition of their independence, despite the defeat they inflicted on the British at Majuba, which was offensive to English pride and required, in the opinion of the patriots, retribution. This compliance is sharply contradicted by the occupation of Egypt in 1882 - insufficiently motivated even from the point of view of British conservatives. Gladstone's repressions in Ireland are in conflict with his liberal activities there. However, Irish repressions and the occupation of Egypt represent only isolated deviations in Gladstone’s activities, sometimes explained by the circumstances of the moment; in general, since 1852, it has been constantly aimed at serving the ideals and interests of that democracy in England, which at the moment was taking an active part in political life.

Gladstone was married from 1839 to Catherine Glynn. The eldest of his four sons, William Henry (1840–1891), was a member of the House of Commons and briefly Lord of the Treasury. The second Stephen was a pastor. The fourth, Herbert John, studied at Eton and Oxford, was a member of the House of Commons from 1880, was his father’s private secretary in 1880–1881, and a junior lord of the treasury in 1881–85 and one of the prominent figures of the Gladstonian party.

Add information about the person

Biography

English statesman. He was repeatedly appointed as a minister in British cabinets.

Since 1868 - leader of the Liberal Party. In 1868-1874, 1885-1885, 1886 and 1892-1894. - Prime Minister. He actively spoke out in favor of ending the Abdul Hamid pogroms of 1844-1896.

It was Gladstone who initiated the presentation of collective notes of the Powers to Turkey on June 11 and September 11, 1880. He owned two catchphrases that have gone down in history.

- First: “Serving Armenia means serving civilization”.

- Second: “The Armenian question is above the internal party struggle and national strife, it concerns all of humanity”.

In his fight against the Conservatives, Gladstone undoubtedly pursued political goals. Member of Parliament from the Liberal Party But during the Ablul-Hamid pogroms of 1894-96. Gladstone took a deeply humanistic position, demanding England's disinterested, decisive intervention in stopping the pogroms. In 1885, at the age of 75, Gladstone helped create a fierce campaign in the country in defense of the Armenians.

On August 6, at a rally in Chester, he declared that the only way to resolve the Armenian Question was to “expel the Turks from Armenia” and sharply condemned the Powers for their position of non-intervention.

A year later, on September 21, 1896, Gladstone gave his famous speech in Liverpool, which lasted one hour and twenty minutes. He said that England must decide to sever relations with the Sultan and to intervene directly, that it must publicly declare that it is not going to derive any benefit from its intervention, but is striving to put an end to the horrors of the pogroms and has prepared reforms. In this speech Gladstone named Abdul Hamid "The Great Killer".

Bibliography

- From illusion to tragedy: The French public on the Armenian question: From the Abdul-Hamid pogroms to the Young Turk revolution (1894-1908) / M. Kharazyan; Translated: M. Kharazyan.-Er.: Author's edition, 2011. ISBN 978-9939-0-0143-2

GLADSTONE William Ewart

(Gladstone, William Ewart) (1809-1898), British statesman of the 19th century. Born 29 December 1809 in Liverpool. William, the youngest of four sons, was educated at Eton and Christ Church College, Oxford University, where he studied theology and ancient authors. In 1832 Gladstone became a member of parliament from the Tory party. In his first speech in 1833 he defended the rights of West Indian slave owners. In 1834-1835 he held minor positions in Peel's government. In 1838 Gladstone's career was in jeopardy. The book he published argued that the state was neglecting its duty towards the Church of England; he also proposed closing access to official positions to nonconformists and Catholics. Macaulay sharply criticized these ideas, and Peel was shocked by the views of his protégé. However, he soon managed to switch Gladstone’s attention from theology to the financial sphere. In 1845 Gladstone lost his seat in parliament because of his free trade views. In 1843-1845 he was Minister of Trade, in 1845-1846 - Minister of Colonies. In 1847 he was elected to parliament from Oxford University. In 1846, like Peel, he left the Tories. In 1852 he refused to join the Derby government, and then contributed to its downfall by brilliantly criticizing the budget presented by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Benjamin Disraeli. In 1852-1856 Gladstone was Chancellor of the Exchequer in the coalition government of Aberdeen and again took this place in 1859-1866 in the government of Palmerston. Thanks to him, this post became the second most important in the government. The pinnacle of the first stage of his career were the budgets of 1853 and 1860, which embodied the principles of laissez faire and the idea of freeing citizens from the burden of fiscal restrictions. It was during this period that he became one of the leaders of the Liberal Party (formed on the basis of the Whig party, which was joined by the Peelites and Free Traders). In 1866 Gladstone presented a draft parliamentary reform, which was not adopted. Nevertheless, his speeches largely forced Disraeli to formulate the Electoral Reform Act of 1867 in the form in which it was subsequently adopted. At this time there was a change in Gladstone's religious beliefs and his attitude towards the High Church with its emphasis on authority and tradition. In May 1864, Gladstone proclaimed in the House of Commons that every person in good health had the right to vote. This infuriated the Liberal leader, Prime Minister Palmerston, and cost Gladstone, to his chagrin, his seat in Parliament as the representative of Oxford University. In 1865, after Palmerston's death, Gladstone became leader of the House of Commons, while remaining Chancellor of the Exchequer. In 1868 Gladstone became prime minister. He considered the main task to be the implementation of several highly moral acts, such as liberating the Balkans from the Turkish yoke, and the Irish from British rule. Among the laws passed during this period: the law on the separation of the Anglican Church and the state in Ireland; the Land Act of 1870, which provided a number of guarantees to Irish tenant farmers; the Education Act of 1870, which introduced a system of primary schools and compulsory education; a law abolishing the sale of positions in the army and religious qualifications at Oxford and Cambridge universities; law introducing a secret voting procedure in parliamentary elections, 1872; a law granting legal rights to trade unions; judicial act, which was followed by a reorganization of the entire judicial system. The Liberals were defeated in the 1874 elections, and in 1875 Gladstone resigned as leader of the Liberal Party, which he had held since 1868. The high point of the second period of Gladstone's career was his campaign in the Scottish county of Midlothian in November 1879 and March 1880, during which he made speeches aimed at against Disraeli's pro-Turkish foreign policy. Gladstone again became prime minister in 1880, and his government remained in power until 1885. During this period, the Irish Land Act of 1881 and the Third Electoral Reform Act of 1884 were passed. In his second term as premier, Gladstone faced a crisis in agriculture and trade. . Cheap food from America was ruining British farmers; higher tariffs limited British exports and caused unemployment and unrest; the growth of armaments in Europe posed a threat to British security. All this contributed to the emergence of two mass movements in British public opinion, demanding a policy of social reform within the country and a tough imperial policy abroad. Both of these demands aroused the indignation of Gladstone, who believed, firstly, that the welfare of the country would be undermined if the state took upon itself the work that each person is obliged to do independently; he also believed that the military-political and financial balance of forces would be disrupted if Great Britain engaged in rearmament or sought to expand its possessions, compensating for the relative decrease in its influence in Europe. However, Gladstone's foreign policy was not consistent. In particular, in 1882 he sent troops to capture Egypt. Gladstone lost popularity after the defeat of British troops in Eastern Sudan in 1884 and an unsuccessful attempt to save General Gordon, who was killed in Khartoum by Sudanese rebels. Gladstone headed the government in 1886; It was then that he introduced a Home Rule Bill for Ireland into Parliament, which was rejected. The last time he was in power was 1892-1894. His efforts during this period were directed mainly at the passage of the Home Rule Bill (which was again rejected by the House of Lords in 1893). Conducting a campaign in defense of the Home Rule bill in the last period of his government activity, Gladstone sacrificed unity in the liberal party: the right wing - liberal unionists (i.e. supporters of maintaining the union with Ireland) broke away, and a significant part of them subsequently joined the conservatives; Radicals left the government in protest against Gladstone's refusal to sanction moderate social reforms. Gladstone died at Hawarden Castle (Flintshire, Wales) on May 19, 1898.

Collier's Encyclopedia. - Open Society. 2000 .

See what "GLADSTON William Ewart" is in other dictionaries:

Gladstone William Ewart- (Gladstone, William Ewart) (1809 98), English. state activist A prominent figure in the political life of Great Britain in the Victorian era, he served as Prime Minister four times. (1868 74, 1880 85, 1886, 1892 94). First elected to parliament from the Tory party in 1832... The World History

- (Gladstone) (1809 1898), Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1868 1874, 1880 85, 1886, 1892 94, leader of the Liberal Party from 1868. Gladstone’s government suppressed the national liberation movement in Ireland and at the same time unsuccessfully sought... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

William Gladstone William Ewart Gladstone ... Wikipedia

Gladstone William Ewart (12/29/1809, Liverpool, 5/19/1898, Harden), English statesman. Born into the family of a wealthy businessman. He received his education at the closed aristocratic school at Eton and at Oxford, where he studied... ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Gladstone, William Ewart- GLADSTONE William Ewart (1809 98), Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1868 74, 1880 85, 1886, 1892 94, leader of the Liberal Party from 1868. Tried unsuccessfully to resolve the Irish question (see Home Rule). Under Gladstone, Great Britain took... Illustrated Encyclopedic Dictionary

- (1809 98) Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1868 74, 1880 85, 1886, 1892 94, leader of the Liberal Party from 1868. Gladstone’s government suppressed the national liberation movement in Ireland and at the same time unsuccessfully sought the adoption of... ... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

- (1809 1898) statesman and writer Alcoholism causes more devastation than the three historical scourges combined: famine, plague and war. You need to dispose of your property with dignity during your lifetime. Man lives on earth not only... Consolidated encyclopedia of aphorisms

This term has other meanings, see Gladstone. William Gladstone William Ewart Gladstone ... Wikipedia

- (Gladstone) William Ewart (1809 98), Prime Minister of Great Britain in 1868 74, 1880 85, 1886, 1892 94, leader of the Liberal Party from 1868. Tried unsuccessfully to resolve the Irish question (see Home Rule). Under Gladstone, Great Britain occupied Egypt in 1882... Modern encyclopedia