- Liverpool, Lancashire, England, Great Britain

- Hawarden Castle[d], Flintshire, Wales, Great Britain

Early life

William Ewart Gladstone was born in Liverpool. His family was of Scottish origin. He was the fifth child (third son) of six children of Sir John Gladstone (1764-1851), a wealthy merchant, a well-educated man who took an active part in public life; in 1827 he was a member of Parliament, and in 1846 he became a baronet. Mother Anna Mackenzie Robertson instilled in William a deep religious feeling and developed in him a love of poetry. From an early age he showed outstanding abilities, the development of which was greatly influenced by the influence of his parents.

His father passed on to him a keen interest in social issues, and at the same time a conservative point of view on them. William was not yet twelve years old when his father, in conversations with him, introduced him to various political issues of the day. John Gladstone was at that time on friendly terms with Canning, whose political ideas had a great influence on the young Gladstone, partly through his father, partly directly.

Gladstone received his initial education at home, in 1821 he was placed at Eton School, where he remained until 1828, and then entered Oxford University, where he graduated in the spring of 1832. The school and the University further contributed to the fact that Gladstone entered life as a supporter of the conservative direction. Recalling Oxford many years later, he said:

I did not take away from Oxford what I acquired only later - the ability to appreciate the eternal and invaluable principles of human freedom. A suspicious attitude towards freedom was too prevalent in the academic environment.

Mentally, he took everything he could from Eton and Oxford; hard work gave him extensive and versatile knowledge and aroused in him a keen interest in literature, especially classical literature. He took an active part in the debates of the Eton Society of Fellows (under the name The Literati) and in the publication of "Eton Miscellany", a periodical collection of works by students, being its energetic editor and the most active supplier of material for it, in the form of articles, translations and even satirical and humorous poems. At Oxford, Gladstone was the founder and chairman of a literary circle (called by his initials - WEG), in which, among other things, he read a detailed essay on Socrates' belief in immortality; He also took an active part in the activities of another Union society, where he made a heated speech against the reform bill - a speech that he himself later called “the mistake of youth.” His comrades even then expected outstanding political activity from him.

Upon leaving the University, Gladstone intended to devote himself to a spiritual career, but his father opposed this. Before deciding on his choice of profession, he took a trip to the continent and spent six months in Italy. Here he received from the 4th Duke of Newcastle (whose son, Lord Lincoln, became close friends with Gladstone at Eton and Oxford) an offer to stand as a Tory candidate from Newark, of which he was elected on December 15, 1832. With his speeches and actions during the election campaign (he had two dangerous rivals), Gladstone attracted everyone's attention.

Career in parliament. Ministerial post under Pyla

Gladstone made his first significant speech in Parliament on May 17, 1833, when discussing the issue of the abolition of slavery. Since then he has been an active participant in debates on a wide variety of issues of current politics and soon gained a reputation for himself as an outstanding orator and a very skillful debater. Despite Gladstone's youth, his position within the Tory party was so noticeable that when a new cabinet was formed in December 1834, Robert Peel appointed him Junior Lord of the Treasury, and in February 1835 moved him to the senior position of Assistant Secretary (Minister) for Administration colonies. In April 1835, Peel's ministry fell.

In the following years, Gladstone took an active part in the opposition, and devoted his free time from parliamentary studies to literature. With special zeal he studied Homer and Dante, and read all the works of St. Augustine. The study of the latter was undertaken by him in order to illuminate some questions about the relationship between the church and the state and had a great influence on the development of those views that he outlined in his book: “The state in its relations to the Church” (1838). This book, in which Gladstone spoke out strongly in favor of the state church, attracted much attention; it, by the way, provoked a lengthy critical analysis of Macaulay, who, however, recognized the author’s outstanding talent and called him “the rising hope of the stern and unyielding Tories.”

Robert Peel was skeptical about Gladstone’s book, saying: “Why would he want to write books with such a career ahead of him!” The famous Prussian envoy, Baron Bunsen, wrote the following enthusiastic lines in his diary: “The appearance of Gladstone's book is the great event of the day; This is the first book since Bork that touches on a fundamentally vital question; the author is above his party and his time.”

When Robert Peel's new ministry was formed in 1841, Gladstone took up the post of Under Secretary of Commerce, and in 1843 he became Secretary of Commerce, becoming a member of the cabinet for the first time, at the age of 33. He actively participated in the debate on the abolition of grain duties; in 1842, he carried out work to revise the customs tariff in the spirit of partly complete abolition, partly reducing duties. Little by little, from a protectionist, Gladstone became an ardent supporter of free trade ideas.

Chancellor of the Exchequer

First cabinet, 1868-1874

The formation of the new ministry was entrusted to Gladstone (in December 1868), who became prime minister for the first time. This first Gladstone cabinet lasted until February 1874; His most important measures: the abolition of the state church in Ireland in 1869, the Irish Land Act of 1870, radical reform in the field of elementary public education in 1870, the abolition of the system of selling positions in the army in 1871, the introduction of secret voting in elections in 1872, etc. d. After the fall of the cabinet, in March 1874, Gladstone, in a letter to Lord Grenville, announced his intention to withdraw from active leadership of the Liberal party. It is curious that he then considered his political career over, telling friends that none of the prime ministers managed to do anything outstanding after the age of 60.

In opposition

In January 1875, in a new letter to Lord Grenville, Gladstone formally announced his resignation from leadership. The Marquess of Hartington was chosen as his successor.

However, already in 1876, Gladstone returned to active participation in political life, publishing a pamphlet: "The Bulgarian Horrors" and taking an energetic part in organizing a social movement against the Eastern Policy of Benjamin Disraeli Lord Beaconsfield. The pamphlet had significant influence: denouncing the "Turkish race" as "one great inhuman specimen of the human race," Gladstone proposed granting autonomy to Bosnia, Herzegovina and Bulgaria, as well as ceasing to provide unconditional support to the Porte.

When, in 1880, Beaconsfield dissolved Parliament, the general election gave a huge majority to the Liberal Party. These elections were preceded by Gladstone's election campaign in Scotland, amazing in its energy and a number of brilliant speeches, in the Midlothian constituency of which he put up his candidacy.

Second Ministry, 1880-1885

The creation of a new ministry was entrusted first to Hartington (who continued to be considered the leader of the liberal party), then to Grenville, but they could not form a cabinet and the queen was forced to entrust this to Gladstone. Gladstone's second ministry lasted from April 1880 to July 1885. He managed to carry out the Irish Land Act of 1881 and the third parliamentary reform (1885).

Third Cabinet, 1886

In June 1885, Gladstone's cabinet was defeated, but Lord Salisbury's new ministry did not last long: after the general elections, in December 1885, a large majority was on the side of the Liberals, due to the accession of the Irish party, and in January 1886 Gladstone's third ministry was formed. By this time there was a decisive turn in Gladstone's views on the Irish question; The main goal of his policy was to grant Ireland home rule (internal self-government). A bill introduced on this subject was defeated, which prompted Gladstone to dissolve Parliament; but new elections (in July 1886) gave him a majority hostile to him. Gladstone's failure was greatly facilitated by a split within the liberal party: many influential members fell away from it, forming a group of liberal unionists. The long period of the Salisbury Ministry began (July 1886 - August 1892). Gladstone, despite his advanced age, took an active part in political life, leading the party of his adherents, which, since the split among the liberals, began to be called the party of “Gladstonians.” He set the implementation of the idea of Home Rule as the main goal of his life; both in Parliament and outside it, he vigorously defended the need to grant political self-government to Ireland.

Fourth Cabinet, 1892-1894

Salisbury was in no hurry to call general elections, and they did not take place until July 1892, that is, just one year before the expiration of the legal seven-year term of Parliament. The election campaign was conducted with great excitement both by supporters of Home Rule and by its opponents. As a result of the elections, the Gladstonians and groups adjacent to them had a majority of 42 votes, and in August, immediately after the opening of the new parliament, the Salisbury cabinet was defeated; a new, fourth Gladstone ministry was formed (this is the first time in the history of England that a politician became prime minister for the fourth time). Having been appointed Prime Minister in his eighty-third year, Gladstone became the oldest Prime Minister of Great Britain in its entire history.

Main directions of political activity

These are the most important facts of Gladstone's long political career. One of its most characteristic features is the gradual change in the political beliefs and ideals of Gladstone, who began his activity in the ranks of the Tories and ended it at the head of the advanced part of English liberals and in alliance with extreme radicals and democrats. Gladstone's break with the Tory party dates back to 1852; but it was prepared gradually and over a long period of time. In his own words, from those with whom he had formerly acted, he "was torn away, not by any arbitrary act, but by the slow and irresistible work of inner conviction." In the literature about Gladstone one can find the opinion that, in essence, he always occupied a completely independent position among his comrades and did not actually belong to any party. There is a lot of truth in this opinion. Gladstone himself once said that parties in themselves do not constitute a good, that a party organization is necessary and irreplaceable only as a sure means to achieving one or another high goal. Along with independence in relation to issues of party organization, it is necessary to note, however, another important feature of Gladstone's political worldview, a hint of which is already in the first speech he delivered to the voters, on October 9, 1832: this is the firm conviction that the basis of political actions "sound general principles" must lie first. The special properties of his outstanding mind, the clarity and logic of thinking developed in him this characteristic feature, which manifested itself early and never weakened. Throughout his entire career, he constantly sought and found a fundamental basis for the views and activities of each given moment. These features served as the source of the revolution in Gladstone's political views and ideals, which took place in him as he became more closely acquainted with the life and needs of the people. Gladstone's political views were constantly in the process of internal evolution, the direction of which was determined by a conscientious and attentive attitude to the general conditions and demands of the country's cultural growth. The more the range of phenomena accessible to his observation expanded, the clearer the democratic movement of the century appeared to him, the more convincing its legitimate demands became. Doubts could not help but arise in him about the justice and correctness of those views that the Conservative Party continued to hold in its opposition to the new trend. Gladstone's inherent desire to find the fundamental basis of any social movement, in connection with his humane worldview, highly honest views on life and demanding attitude towards himself, helped him come to the correct answer to the question of where is the truth, where is justice. As a result of prolonged internal work to clarify the doubts that arose, his final transition to the ranks of the liberal party was achieved.

A remarkable feature of Gladstone's political activity is also the predominant position that issues of internal cultural development always had in it over the interests of foreign politics. This latter, during the periods when he was the first minister, caused especially strong criticism from his opponents, and in 1885, for example, served as the immediate cause of the fall of his cabinet. In this area he was most vulnerable, but only because he was never inclined to attach primary importance to international issues and has views on them that differ too sharply from the point of view that prevails in European countries today. According to his fundamental convictions, he is an enemy of war and all violence, the manifestations of which are so rich in the field of international politics. While the merits of Gladstone's famous rival, Lord Beaconsfield, boil down mainly to a series of deft diplomatic moves and deals, the list of Gladstone's great deeds for the benefit of England covers only issues of its internal life. The definition of the role of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, which Gladstone made back in 1850, in a dispute with Lord Palmerston over Greek affairs, is very characteristic. His task is “to preserve peace, and one of his first duties is the strict application of that code of great principles that was bequeathed to us by previous generations of great and noble minds.” He ended this speech with a warm invitation to recognize the equality of the strong and the weak, the independence of small states, and generally refuse political interference in the affairs of another state.

In his political activities, however, Gladstone more than once touched upon the interests of other states and intervened in other people's affairs, but this intervention took on a unique form. So, Gladstone spent the winter of 1850-1851 in Naples. At that time, the government of King Ferdinand II, nicknamed “Bomba” for his cruelty, carried out brutal reprisals against those citizens who took part in the movement against the intolerable regime: up to twenty thousand people were imprisoned without investigation or trial in gloomy prisons in which conditions the existence was so terrible that even serving doctors did not dare to enter there for fear of infection. Gladstone carefully studied the state of affairs in Naples and was filled with indignation at the sight of this gross barbarity. In the form of “Letters to the Earl of Aberdeen,” he announced the details of all the horrors that he had to know and see. Gladstone's letters made a huge impression throughout Europe and did not remain without influence on subsequent events in Italy.

In the name of the same ideals of justice and humanity, Gladstone raised his voice against the horrors of Turkish rule in Bulgaria revealed in 1876 (in the pamphlet: “Bulgarian Horrors and the Eastern Question”). Gladstone in his speeches expressed the opinion that an Islamic state cannot be good and tolerant towards “civilized and Christian races”, and also that as long as there are followers of “this damned book” (the Koran), there will be no peace in Europe. In 1896, he zealously supported the demands of the powerful Armenian lobby for a British military invasion of the Ottoman Empire as a "Christian duty" of the government. However, the queen condemned Gladstone's "unreasonable and crazy attitude." O. A. Novikova Homer had an undoubted influence on Gladstone's views. In 1858 he published an extensive study entitled: "Studies on Homer and Homeric Age"; in 1876 - “Homeric Synchronism”, and later - a number of small studies about Homer. In addition, he wrote a large number of articles on a wide variety of issues - philosophical, historical, constitutional, on the phenomena of current literature, on various political issues of the day, etc. For their separate publication, in 1879, it took seven volumes of the collection, under entitled "Gleaning of Past Years". In 1886, Gladstone engaged in a lively journal debate with Professor Huxley over the relationship between science and religion. In recent years he has written a number of articles on the Irish question. The December 1892 issues of Notes und Queries published a detailed bibliography of everything Gladstone had written since 1827. Gladstone's speeches, both in and outside Parliament, were published many times, but it was not until 1892 that the complete collection of his speeches was published, under his personal supervision. So far, only one volume has been published, the tenth, in which his speeches for the years 1888-1891 were published, mainly on the Irish question (“The Speeches and Public Addresses of W. E. Gladstone, with Notes and Introductions”).

) . The infidel within: Muslims in Britain since 1800. - C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2004. - P. 80. - 438 p. - ISBN 1850656851, ISBN 9781850656852.Pronouncements made at regular intervals by giants from the Liberal Party in the late Victorian and Edwardian period were vehement against Islam and the Ottoman Turks. W.E. Gladstone expressed his deeply-rooted suspicion of Islam, which he thought "radically incapable of establishing a good and tolerable government over civilized and Christian races". In a public speech he asserted that for as long as there were followers of “that accursed book” (the Quran), Europe would know no peace. In his view Europe-in other words Christendom-should have united to impose its will. Only over "lesser" peoples such as the so-called "Orientals" and "Mahomedans", where there was no "complication of blood, of religion, or tradition, or speech", did Gladstone accept the Turks" ability to imperial provide rule So firm was his belief in the reality of Muslims" fanaticism and their capacity to commit atrocities against Christians that he completely accepted Bulgarian suspicion of massacres in 1876 and reports of Armenian persecution in the 1890s, ignoring any evidence that pointed to similar acts committed against the Turks. Consequently his passionate and immensely popular pamphlet, The Bulgarian Horrors, or The Question of the East, reinforced British perceptions of Muslims as an "anti-human specimen of humanity". Not surprisingly such rhetoric encouraged an outpouring of anti-Turkish emotion and agitation.

GLADSTONE, WILLIAM EWART(Gladstone, William Ewart) (1809–1898), British statesman of the 19th century. Born 29 December 1809 in Liverpool. William, the youngest of four sons, was educated at Eton and Christ Church College, Oxford University, where he studied theology and ancient authors.

In 1832 Gladstone became a member of parliament from the Tory party. In his first speech in 1833 he defended the rights of West Indian slave owners. In 1834–1835 he held minor positions in the Peel government. In 1838 Gladstone's career was in jeopardy. The book he published argued that the state was neglecting its duty towards the Church of England; he also proposed closing access to official positions to nonconformists and Catholics. Macaulay sharply criticized these ideas, and Peel was shocked by the views of his protégé. However, he soon managed to switch Gladstone’s attention from theology to the financial sphere.

In 1845 Gladstone lost his seat in parliament because of his free trade views. In 1843–1845 he was Minister of Trade, in 1845–1846 – Minister of Colonies. In 1847 he was elected to parliament from Oxford University. In 1846, like Peel, he left the Tories. In 1852 he refused to join the Derby government, and then contributed to its downfall by brilliantly criticizing the budget presented by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Benjamin Disraeli.

In 1852–1856 Gladstone was Chancellor of the Exchequer in the coalition government of Aberdeen and again took up the position in 1859–1866 in the government of Palmerston. Thanks to him, this post became the second most important in the government. The pinnacle of the first stage of his career were the budgets of 1853 and 1860, which embodied the principles of laissez faire and the idea of freeing citizens from the burden of fiscal restrictions. It was during this period that he became one of the leaders of the Liberal Party (formed on the basis of the Whig party, which was joined by the Peelites and Free Traders). In 1866 Gladstone presented a draft parliamentary reform, which was not adopted. Nevertheless, his speeches largely forced Disraeli to formulate the Electoral Reform Act of 1867 in the form in which it was subsequently adopted. At this time there was a change in Gladstone's religious beliefs and his attitude towards the High Church with its emphasis on authority and tradition. In May 1864, Gladstone proclaimed in the House of Commons that every person in good health had the right to vote. This infuriated the Liberal leader, Prime Minister Palmerston, and cost Gladstone, to his chagrin, his seat in Parliament as the representative of Oxford University. In 1865, after Palmerston's death, Gladstone became leader of the House of Commons, while remaining Chancellor of the Exchequer.

In 1868 Gladstone became prime minister. He considered the main task to be the implementation of several highly moral acts, such as liberating the Balkans from the Turkish yoke, and the Irish from British rule. Among the laws passed during this period: the law on the separation of the Anglican Church and the state in Ireland; the Land Act of 1870, which provided a number of guarantees to Irish tenant farmers; the Education Act of 1870, which introduced a system of primary schools and compulsory education; a law abolishing the sale of positions in the army and religious qualifications at Oxford and Cambridge universities; law introducing a secret voting procedure in parliamentary elections, 1872; a law granting legal rights to trade unions; judicial act, which was followed by a reorganization of the entire judicial system.

The Liberals were defeated in the 1874 elections, and in 1875 Gladstone resigned as leader of the Liberal Party, which he had held since 1868. The high point of the second period of Gladstone's career was his campaign in the Scottish county of Midlothian in November 1879 and March 1880, during which he made speeches aimed at against Disraeli's pro-Turkish foreign policy.

Gladstone again became prime minister in 1880, and his government remained in power until 1885. During this period, the Irish Land Act of 1881 and the Third Electoral Reform Act of 1884 were passed. In his second term as premier, Gladstone faced a crisis in agriculture and trade. . Cheap food from America was ruining British farmers; higher tariffs limited British exports and caused unemployment and unrest; the growth of armaments in Europe posed a threat to British security. All this contributed to the emergence of two mass movements in British public opinion, demanding a policy of social reform within the country and a tough imperial policy abroad. Both of these demands aroused the indignation of Gladstone, who believed, firstly, that the welfare of the country would be undermined if the state took upon itself the work that each person is obliged to do independently; he also believed that the military-political and financial balance of forces would be disrupted if Great Britain engaged in rearmament or sought to expand its possessions, compensating for the relative decrease in its influence in Europe. However, Gladstone's foreign policy was not consistent. In particular, in 1882 he sent troops to capture Egypt. Gladstone lost popularity after the defeat of British troops in Eastern Sudan in 1884 and an unsuccessful attempt to save General Gordon, who was killed in Khartoum by Sudanese rebels.

Gladstone headed the government in 1886; it was then that he introduced the Home Rule Bill for Ireland into Parliament, which was rejected. He was last in power in 1892–1894. His efforts during this period were directed mainly at the passage of the Home Rule Bill (which was again rejected by the House of Lords in 1893). Conducting a campaign in defense of the Home Rule bill in the last period of his government activity, Gladstone sacrificed unity in the liberal party: the right wing - liberal unionists (i.e. supporters of maintaining the union with Ireland) broke away, and a significant part of them subsequently joined the conservatives; Radicals left the government in protest against Gladstone's refusal to sanction moderate social reforms.

GLADSTONE WILLIAM Ewart (eng. William Ewart Gladstone) - English statesman, prime minister in 1868-1874, 1880-1885, 1886, 1892-1894.

Gladstone was born into the family of a wealthy Scottish businessman. The formation of William's personality was greatly influenced by his parents, who managed to instill in their son a deep faith in God, a love of literature and an interest in public affairs. He graduated from school at Eton (1821-1828), then studied at Oxford (Christ Church College), where he discovered an interest in theology and was one of the best students. Gladstone dreamed of devoting himself to serving God, but his father saw his son’s future in the political field and forbade him to take ordination. Having completed his education, in 1832 Gladstone went on a trip to Italy, after visiting which he changed his attitude towards Catholics. In Rome, he said, he especially felt the loss of unity in the Christian world and for some time after his return, while remaining an evangelical, he was carried away by the ideas of the Oxford movement.

Gladstone began his political career as a Tory, sharing conservative views on major issues of domestic and foreign policy. He was a supporter of repressive measures against Ireland, opposed the admission of Jews to parliament, dissenters into the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, and also opposed the abolition of corporal punishment in the army. He was an opponent of the parliamentary reform of 1832 and the ban on slavery. At the age of 23 he won the parliamentary elections. Gladstone's program included maintaining the union of the Anglican Church and state. Subsequently he considered himself an Anglican. The Church, being one of the branches of the united Catholic Church (the so-called Branch Theory), retained its own doctrines and organization.

From 1832 and for 63 years, Gladstone consistently took an active position and spoke in Parliament on all the most important issues.

In 1834-1835 he was a member of the 1st Conservative government of R. Peel. In 1838, Gladstone published The State in Its Relations with the Church, which was a defense of the status of the state Church. Gladstone argued that the purpose of the state was to serve religion, and the Church in this union needed state support. The book was a young man’s reaction to the granting of political and civil rights to Catholics in 1829 (the so-called emancipation of Catholics) and the demands of nonconformists to eliminate the state status of Anglicans. Church and caused heated debate in society. In subsequent years, Gladstone's books and articles were devoted to church history and theology. He wrote essays on the history of the Reformation, works on the authenticity and authority of Holy Scripture, etc.

Gladstone's deep inner religiosity remained unchanged, but his views on issues of domestic and foreign policy of the state underwent serious changes, which over time led him to the liberal camp. The revision of the position was the result of deep reflection, flexibility of mind, openness to new trends, facts, phenomena, and the ability to abandon delusions. Gladstone understood the need to implement changes in the social and political areas, which were opposed by the extreme Tories. As Minister of Trade in 1843-1845 in Peel's 2nd cabinet, Gladstone supported his policy of establishing liberal principles of trade (free trade) and encouraged the development of railway construction. He spoke out for the expansion of self-government in the colonies, which was sought by the colonists and radicals. His position indicated a transition to the camp of liberal conservatives, supporters of Peel's policies. Gladstone's resignation in 1845 was caused by his opposition to an increase in subsidies for Catholic colleges in Ireland. Gladstone was convinced that the state should support only the dominant Anglican religion.

In the 50s, he finally broke with the conservatives and entered the coalition governments of Aberdeen (1852-1855) and the Liberal cabinet of Palmerston (1859-1866). After the death of G.J. Palmerston Gladstone became leader of the Liberals in the House of Commons in 1868. Gradually he came to religious tolerance. Reflections led him to the conviction of the need to strengthen religious institutions and change the nature of the relationship between the Church and the state. In 1865 he declared the unsatisfactory position of the Anglicans. Churches in Ireland. The Church relied on a minority of the population, but the Catholic majority supported it financially by paying tithes. Therefore, the first law of the Gladstone government in 1869 was the elimination of the state status of the Anglican Church in Ireland. According to the law, the provision of maintenance to priests was stopped, all church property was transferred into the hands of a royal commission; Irish bishops lost their seats in the House of Lords; Church courts were abolished. Gladstone believed that the law would help pacify the Catholic population of Ireland, but these actions caused violent indignation among Gladstone's opponents. Oxford University, which he represented in Parliament from 1847 to 1865, severed all ties with him. However, Gladstone had no doubt that he was right and in 1890 spoke about the need for similar changes in Scotland and Wales. Gladstone's first cabinet went down in history as a reform government. Administrative reform was carried out, the principles of admission to civil and military service were revised; the system of selling positions was abolished; secret voting was established for parliamentary elections; universal primary education was introduced; trade unions are legalized; The Land Act was passed, limiting the rights of landlords in Ireland. Colonial policy was aimed at expanding the sphere of influence of Great Britain and providing the settler colonies with greater independence, which consisted of developing forms of self-government, expanding economic ties between the mother country and dominions based on the principles of free trade: freedom of trade and non-interference of the state in private business activities.

After the resignation of the cabinet, Gladstone resigned as leader of the Liberal Party, believing that his political career was over. He wanted to pay more attention to issues of religious and spiritual life. The strengthening of Catholicism and nonconformism, as well as the successes of natural sciences, caused a new wave of interest in religious problems in society in the 60-80s. Gladstone believed that the decisive time had come for the struggle “for minds” in matters of faith. In the mid-70s, he published a number of works in defense of the principles of religious freedom, for example against the Vatican. A major role in the evolution of Gladstone’s views towards ecumenism was played by the so-called. the case of Bradlow, an atheist who was elected to parliament in 1880, but did not become a deputy due to his refusal to take the oath, which spoke of faith in God. Reflections on the current situation led Gladstone to the opinion about the possibility of separation of Church and state, to tolerance in matters of faith. In a parliamentary speech in 1883, Gladstone spoke of the need to separate the question of religious difference from the question of civil rights and power. In 1880-1885, Gladstone's 2nd government continued the electoral reforms of 1884 and 1885, as well as the expansionist policies of its Conservative predecessors, intervening in the Egyptian conflict and suppressing opposition movements in Ireland. At the same time, Gladstone was looking for ways to solve the Irish problem and carried out the 2nd land reform (1881). By 1886, Gladstone became convinced of the need for further changes in England's policy towards Ireland and, during his 3rd stay in power, proposed introducing self-government (Home Rule) in it. The Home Rule law failed, which led to the resignation of the government. Disagreements over Irish politics caused a split in the Liberal camp and weakened Gladstone's position. In 1892-1894, Gladstone managed to pass the Home Rule Act through the House of Commons, but the House of Lords voted against it and the law did not come into force.

Gladstone's early life

Gladstone William Ewart (Ewart) - famous English politician, born December 29, 1809, died May 19, 1898. His father, John Gladstone, a Scot by birth, a wealthy merchant who settled in Liverpool, was a Conservative member of the House of Commons in 1819 - 1827 . Young William Gladstone brought from home a rare work ethic, deep orthodox Anglican religiosity, and excellent home training. Already during his school years spent at Eton (1820 - 1827), he discovered at meetings of various school circles a strong oratorical talent, a versatile education, which was reflected in his numerous articles in the school (printed) magazine Eton Miscellaneous, published in 1827 under his editorship, and the ability to make a deep impression on everyone around you. Brought up under the influence of his father, as well as Canning, who was a close friend of his father, Gladstone, who at that time dreamed of either a spiritual career or a career as a political figure, was a definite conservative of the Canning shade. During his student years (1829 - 1832), which he spent at Oxford, Gladstone's conservatism remained unshaken; At meetings of student political societies, in which he took an active part, he made speeches against parliamentary reform, against the emancipation of slaves in the colonies, and for the patrimonial aristocracy. Having completed his university course with double honors in ancient languages and mathematics, he traveled around Italy. At the end of 1832, Gladstone was elected a member of the House of Commons in the Newark district, which was under the strong influence of the Duke of Newcastle, who patronized him.

William Gladstone's first speech in the House of Commons was devoted to the issue of slavery in the English colonies; While not unconditionally opposed to emancipation in principle, Gladstone found it untimely, insisted on the need to reward slave owners, and in particular defended his father against the charges brought against him for the mistreatment of slaves on his sugar plantations. This speech and, in general, Gladstone’s activities in the House of Commons so quickly promoted him in the ranks of the Tories that already in 1834 Robert Peel upon taking office as head of government, he was offered the post of first junior lord of the treasury, and a few months later assistant secretary of the colonial affairs. In 1835, William Gladstone retired along with the ministry of Robert Peel.

He devoted the following years, in addition to his current parliamentary studies, to an in-depth study of Homer, Dante and St. Augustine. The fruit of the study of theological literature was the books “The State in its Relations to the Church” (1838) and “The Principles of the Church, Evaluated by Their Results” (1840); in them Gladstone, based on the idea that the state, as such, “has a conscience,” argued for the need for the state to support and spread the Christian religion with the help of the state church. At this time, the future liberal Gladstone, according to Macaulay, was still “the rising hope of the stern and unyielding Tories” who followed Peel, horrifying him.

Gladstone's evolution from conservative to liberal

In 1841, R. Peel appointed Gladstone as associate president of the Bureau of Trade, and in 1843 as president; at the same time, William Gladstone became a member of the cabinet. During the execution of this position, a significant change took place in Gladstone, as well as in R. Peale. From extreme protectionists and in particular supporters of agrarian protectionism, they, gradually softening, became supporters of the abolition of the Corn Laws, and then free traders (adherents of free international trade). At this time, Gladstone carried out significant work on revising the customs tariff in the direction of its significant softening, and then spoke out for the repeal of the Corn Laws. However, the implementation of this last measure was no longer Gladstone’s business, since in February 1845 he resigned due to disagreement with R. Peel’s promise of a state subsidy for a Catholic educational institution in Ireland.

At the end of 1845, William Gladstone re-entered the cabinet as Colonial Secretary, but, having at the same time lost his seat in the House of Commons, did not consider it possible to appear before the voters of Newark, which was under the influence of the strictly conservative Duke of Newcastle. Only in 1847 was he re-elected as a member of the House of Commons from Oxford University. From 1846 to 1852, Gladstone was a prominent member of the opposition (the Peelite party) against the liberal ministry of Rossel; however, this opposition was far from conservative. Gladstone supported government measures such as the emancipation of the Jews; at the same time, he was a resolute opponent of the Lord's aggressive foreign policy Palmerston. In 1850, when Palmerston presented the Greek government with a demand for the payment of a significant remuneration to the English subject Pacifico, and motivated this by the need to achieve exceptional respect for the title of the English subject, so that he could proudly say everywhere, like an ancient Roman, “civis romanus sum” (“I am Roman citizen"), then Gladstone, in a remarkable speech, attacked this chauvinistic principle as unchristian.

William Gladstone spent 1850–1851 in Italy. Its political system and in particular the situation of prisoners in prisons in the Kingdom of Naples attracted his close attention, and he published the result of his study in the form of two letters to Lord Aberdeen “Two letters to the earl of Aberdeen on the state prosecutions of the Neapolitan government "; in these letters he severely castigated the despotism of the Neapolitan king, the arrests of the best citizens of the state without trial by administrative order, and especially the situation of prisoners in prisons. The letters made a deep impression throughout Europe and, although they could not have any immediate practical impact, they aroused special respect for Gladstone in Italy and brought him closer to many members of the " Young Italy" In 1852, the Earl of Derby, when forming a cabinet, offered Gladstone a place in it, but Gladstone refused; this refusal marked his final break with the Conservative Party. He even made severe criticism of the budget introduced by the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Disraeli.

Also in 1852, William Gladstone became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Liberal-Pilite coalition cabinet of Lord Aberdeen. The policy of the cabinet, despite the constant peace-loving statements of the Prime Minister himself and Gladstone, led to a war with Russia (see the Crimean War), for which Gladstone shared some responsibility, and which is in undoubted contradiction with the fundamental statements made by Gladstone in his dispute with Palmerston 1850. Since 1855, with the fall of the Aberdeen cabinet, Gladstone went into opposition. He protested against Chinese expedition of Lord Palmerston 1857, and contributed to Palmerston's defeat in the House of Commons on this issue. He remained in opposition during the administration of Derby (1858 – 1859). He took advantage of the comparative leisure to finish a large three-volume work on Homer, “Studies on Homer and the Homeric Epoch” (1858), to which Juventus mundi is adjacent in content. Gods and Men of the Homeric Age" (1869), "Homeric synchronism" (1876), "Landmarks of Homeric studies" (1890) and some minor works of Gladstone. They express Gladstone's conservative mindset in an original way, forcing him to treat all traditions with the deepest respect, but not preventing him from being a political reformer. In these works, Gladstone proves the historical authenticity of the Trojan War, the historical reality of the personality of the poet Homer, who glorified this war, and the unity of the poems of the Iliad and Odyssey. In his attitude to these facts, he is not only behind Wolf and other modern philologists, but even behind the New Alexandrian scientists, since he proves the authenticity of those poems that they had already suspected. Nevertheless, these works belong to remarkable studies. Incidentally, Gladstone put forward the theory (later rejected) that the ancient Greeks were not able to see the color blue.

In 1858, Gladstone accepted an assignment from the office of the Earl of Derby to travel to the Ionian Islands as an English commissioner to resolve the issue of the fate of these islands; Gladstone presented a report on the need to annex the islands in Greece, which was carried out by the next ministry of Lord Palmerston. In this ministry in 1859, Gladstone, despite significant disagreements between him and the prime minister, agreed to assume the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. The following years revealed a remarkable financier in William Gladstone. Under him, a long series of reforms were carried out in the financial system of England in a democratic direction; by the way, the paper tax was abolished, postal savings banks were introduced, the national debt was reduced, etc. In the field of foreign policy, Palmerston's ministry supported the South American States in their struggle with the North, and Gladstone defended this policy. In the elections of 1865, Gladstone was voted out of office at the Conservative University of Oxford, but received a parliamentary mandate for South Lancashire (which he had to replace in 1868 with a mandate for Greenwich, and in 1880 for Midlothian, whose representative he remained until the end of his parliamentary career in 1895).

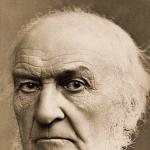

William Gladstone, photo 1861

After Palmerston's death (1865), William Gladstone retained his post in Lord Rossel's cabinet and at the same time took the place of leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons. In 1866 he introduced a parliamentary reform bill into the House. The failure of the bill forced the ministry and Gladstone to resign. However, this bill was introduced in a modified form by the new Conservative cabinet of Derby-Disraeli, and Gladstone, having made some significant amendments to it, was a strong supporter of it.

Gladstone's first cabinet

After new elections (1868), which gave a significant majority to the Liberal Party, the Queen entrusted the composition of the cabinet to Gladstone. The first cabinet of William Gladstone (1868 - 1874), supported by a large majority in the House of Commons and strong support in public opinion, was rich in reform activities. In 1869, church and state were separated in Ireland. To justify himself from the charge of betrayal of the principles he set forth in his books on the relationship of church to state, Gladstone published “A chapter of autobiography” (Lond., 1869), in which he explained the motives that forced him to abandon his previous views. In 1870, the Irish Land Act was passed, which eased the situation of Irish tenants of plots from English landlords, and a law on compulsory education; in 1871, the sale of positions in the army was abolished; in 1872, a system of secret voting in parliamentary elections was introduced.

After the elections of 1874, which gave a significant majority to the Conservatives, Gladstone wanted to abandon political activity; The Marquis of Hartington was elected leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons in his place. In 1876, Gladstone published the famous pamphlet, immediately translated into all languages, “Bulgarian Horrors,” and organized a social movement against Turkey and the Turkophile policies of Disraeli’s conservative English government. Thanks to this movement, Disraeli-Beaconsfield was unable to actively intercede for Turkey during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878.

Gladstone's second cabinet

In 1880, new elections again gave a majority to the Liberal Party, and Gladstone formed his second cabinet (1880 - 1885). The main task that the cabinet had to resolve was the pacification of Ireland. In 1881, Gladstone carried out a new Irish Land Act, but since this measure did not calm the anti-English movement in the country, he decided to apply severe repressive measures to the Irish, the implementation of which was entrusted to the Secretary of Irish Affairs Forster. The Irish Land League (the main body of national resistance to the British) was closed; Habeas Corpus Act has been repealed in Ireland. The most prominent Irish figures, including Parnell, were arrested. Since this system also did not achieve its goal, Gladstone entered into negotiations with the arrested Parnell and concluded an agreement with him, on the basis of which Parnell and his comrades were released, Forster was replaced by Cavendish, and some conciliatory measures were promised. But Cavendish was killed by Irish patriots - Fenians immediately after arriving in Dublin, and this gave Gladstone a reason to once again take the path of harsh repressive measures. In 1882 Gladstone's cabinet bombed Alexandria and occupied Egypt, turning it into an English colony. In 1884, the same cabinet carried out a third parliamentary reform, which again increased the number of Englishmen who had the right to elect members of the chamber. In 1885 clash between England and Russia in Afghanistan almost led to war. Gladstone's acquiescence to Russia led to Gladstone's defeat in the House of Commons, which forced his resignation on June 9, 1885.

Gladstone's third cabinet

But after new elections in January 1886, William Gladstone formed his third cabinet, which included Chamberlain, Morley and other radicals, and did not include Gladstone's former allies, moderate liberals Goshen, Hartington and others. Chamberlain, however, soon left the government. The need to support the Irish party in the House forced Gladstone to agree with it, and he introduced the famous draft Home Rule(autonomy) for Ireland, from which begins an era in the history of the liberal party of England and in the life of Gladstone himself. A significant part of the liberal party, led by Hartington and Chamberlain, not wanting Irish autonomy, formed a new party liberal unionists. The rest of the liberals, led by Gladstone, have since received the name Gladstonians and have shown a clear attraction to radicalism. The Home Rule project led to the defeat of the ministry in the chamber, and after its dissolution, to defeat in the new parliamentary elections. Gladstone ceded the post of head of cabinet to the Marquis Salisbury and became the leader of the opposition.

William Gladstone devoted the next six years of relative leisure between his third and fourth cabinets to passionate agitation for Irish Home Rule, which he conducted in the House of Commons, at countless rallies and in the press; then - writing a number of articles on the situation in Italy, in which he severely condemned the policy Krispy, a number of works in the form of books (“The impregnable rock of Holy Scripture”, 1892) and many articles in various journals on theological issues, in which he, among other things, polemicized with Huxley And Darwinism and defended the truth of the Mosaic cosmogony. In 1890, when the court ordered a divorce between the O'Shea spouses and found the leader of the Irish movement Parnell guilty of adultery, Gladstone declared that it was impossible for him to continue relations with the Irish party while Parnell was its head, and thereby dealt the latter a severe blow. In 1891, At the annual meeting of the National Liberal Federation in Newcastle, William Gladstone made a remarkable speech in which he outlined a new program for the Liberal Party. This program included: Home Rule for Ireland, separation of church and state in Wales and Scotland, a new democratic reform of suffrage, adoption of the the state account for the costs of the electoral struggle, the introduction of salaries for members of parliament, the expansion of local self-government, the end of the occupation of Egypt. Reform of the House of Lords (which had the right to override the decisions of the House of Commons) was planned conditionally if “the lords do not show prudence.”

Gladstone shortly before his death

Gladstone's Fourth Cabinet

During the election of 1892, “the great old man” Gladstone, as he was called, showed remarkable activity, astonishing in his old age. The election gave a majority of 42 votes to the Gladstonians in alliance with the Irish, and Gladstone formed his fourth cabinet. This cabinet passed Home Rule for Ireland through the House of Commons, but it was defeated by the House of Lords, just like some of Gladstone's other liberal bills. This time Gladstone did not have enough energy to fight the lords, and he, suffering from eyes and some deafness, retired in March 1894; his place was taken by Earl Rosebery. Gladstone no longer spoke in the 1895 elections. After a long illness, he died in 1898 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, near the grave of his long-term political rival, Lord Beaconsfield (Disraeli).

Assessment of the personality and activities of William Gladstone

The whole life of William Gladstone represents one slow and steady process of transition from one camp to another, a transition that is far from being fully explained by a change in the political mood of those social classes of which Gladstone could be considered a representative. This political evolution of his is largely a matter of a personal change in his way of thinking. At the beginning of his career, Gladstone acted as a representative of the interests of the aristocratic class, then he defended the interests of the middle and petty industrial bourgeoisie, and at the end of his life he began to become intensely interested in social issues. Previously a strong opponent of legislative regulation of the working hours of adult men, he now wavered in his conviction. In connection with this change of heart, one important change took place in Gladstone. In his own words, neither Eton nor Oxford taught him to sufficiently respect a person’s personal freedom, the importance of which he later appreciated.

The constant work of remaking his own views resulted in some inconsistency, not only between the actions of William Gladstone in different eras, but also between his policies of the same period. Thus he discovered remarkable compliance towards Boers of South Africa, the war with which, inherited (1880) from the Beaconsfield cabinet, he stopped with England's voluntary recognition of their independence, despite the defeat they inflicted on the British at Majuba, which was offensive to English pride and required, in the opinion of the patriots, retribution. This compliance is sharply contradicted by the occupation of Egypt in 1882 - insufficiently motivated even from the point of view of British conservatives. Gladstone's repressions in Ireland are in conflict with his liberal activities there. However, Irish repressions and the occupation of Egypt represent only isolated deviations in Gladstone’s activities, sometimes explained by the circumstances of the moment; in general, since 1852, it has been constantly aimed at serving the ideals and interests of that democracy in England, which at the moment was taking an active part in political life.

Gladstone was married from 1839 to Catherine Glynn. The eldest of his four sons, William Henry (1840–1891), was a member of the House of Commons and briefly Lord of the Treasury. The second Stephen was a pastor. The fourth, Herbert John, studied at Eton and Oxford, was a member of the House of Commons from 1880, was his father’s private secretary in 1880–1881, and a junior lord of the treasury in 1881–85 and one of the prominent figures of the Gladstonian party.

Gladstone William Yuart Gladstone Career: Actor

Birth: 29.12.1809

English historiography, without proper grounds, created Gladstone's reputation as a great statesman. K. Marx used the expression “great” in quotation marks to Gladstone, calling him an arch-hypocrite and a casuist.

Gladstone William Ewart (12/29/1809, Liverpool, 5/19/1898, Harden), British statesman. Born into the family of a wealthy businessman. He received his education at the closed aristocratic school at Eton and at Oxford, where he studied theology and classical literature. In 1832 he was elected to parliament from the Tory party. However, gradually realizing that the formation of capitalism and the strengthening of the bourgeoisie were making ancient Toryism unpromising, G. began to focus on the liberals. In 184345, Minister of Trade in the Peel government, in 184547 Minister of Colonies. In 185255 Minister of Finance in the coalition government of Aberdeen. In 185966 Minister of Finance in the Liberal government of Palmerston; During the American Civil War, 186165 supported the slave owners of the Southern states. In 1868 he was elected leader of the Liberal Party. In 186874 Prime Minister; its leadership reformed primary education, legalized trade unions (at the same time introducing retribution for strikers picketing enterprises to combat strikebreakers), and introduced secret voting in elections. After the defeat of the liberals in the parliamentary elections of 1874, G. led the opposition to the conservative government of Disraeli. Having become the head of the government in 188085, G. continued the expansionist foreign policy of the conservatives. In 1882, Georgia's leadership sent British troops to capture Egypt. In Ireland, while brutally suppressing the national liberation movement, the Irish leadership at the same time made minor concessions. The defeat of British troops in Sudan and complications in Ireland led to the fall of G.'s government. Having headed the leadership for a short time in 1886, G. introduced a bill on Home Rule to parliament, the failure of which prompted him to resign. The fight over this issue dragged on. Again leading the leadership in 189294, G. carried the same bill through the House of Commons, but the House of Lords rejected it. G. once again retired, and his more than 60-year political career ended.

English historiography, without proper grounds, created G.'s fame as a great statesman. K. Marx applied the expression “great” in quotation marks to G., calling him an arch-hypocrite and a casuist.

Also read biographies of famous people:

William McMahon William McMahon

Australian statesman, Prime Minister from March 1971 to December 1972. McMahon replaced George Gorton as leader of the Conservative...

William Pitt

Second son of William Pitt, English statesman (1759-1806).