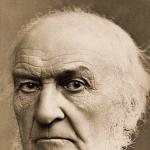

Years of life: from 09/26/1892 to 08/31/1941

Russian poetess, prose writer, translator, one of the largest modernist poets of the Silver Age.

Marina Ivanovna was born on September 26, 1892. Her mother, Maria Alexandrovna Main, had a great influence on the upbringing and education of Marina Tsvetaeva and her sister. The magnificent pianist put her entire musical soul into the children. All of Tsvetaeva’s poems are very musical, and it is not without reason that the words of many of them are set to music. However, Marina was not drawn to music; later she would describe her childhood in the prose “Mother and Music.” Due to her mother's illness, Marina spent a lot of time abroad and learned German and French. In 1909, she took courses in French literature at the Sorbonne. Marina grew up a rebel; in her youth she was a fan of Napoleon, whose room was full of his portraits, as well as heroes of the twelfth year. Later she will walk around in men's trousers and with a cigar in her hands, saying: “Everything falls off like skin, and under the skin there is living meat or fire. I am Psyche. I don’t fit into any form - even the simplest of my poems.”

Marina marries Sergei Efron early.

The development of Marina’s creativity was influenced by the Symbolists who in her youth made up her social circle, especially the Bryusovs. Marina remains true to her romantic nature for some time, but the revolution changes Marina's life. Finding herself without money and housing, the mother of two children, Marina experiences all the hardships of mortal life. The revolution not only took away, but also gave: it sobered her up. “The Bolsheviks gave me good Russian,” she writes later. “The revolution taught me about Russia.” This determined the further development of Tsvetaeva’s talent and creativity, the philosophical depth, psychological accuracy and expressiveness of the style of her works. During the emigrant period, her prose enjoyed greater success than her lyrics: “Mother and Music”, “My Pushkin”, “Emigration makes me a prose writer...”, “The House of Old Pimen”, “The Tale of Sonechka” and others.

In 1922, Marina left to join her husband in Prague. The vastness of miles and years that separated him from Russia became an oppressive burden, a drama of Tsvetaev’s fate.

Marina had a hard time surviving Hitler’s seizure of Czechoslavakia, where she found refuge after Russia left, and then the death of the Spanish Republic, expressing her pain in “Poems to the Czech Republic.”

After the forced flight of Tsvetaeva’s husband from France, who repented of his “White Guard” past, the emigrant environment closed the door for Marina. In 1939, Marina decides to return to Russia. Her daughter and husband are arrested. There is no housing. No money left. Marina has no more strength. Attempts to release the book are unsuccessful. Having written the poem “To My Poems” in 1913, Marina predicted the future of her poems:

"My poems about youth and death

Unread verses! -

Scattered in the dust around the shops

(Where no one took them and no one takes them),

My poems are like precious wines,

Your turn will come."

“I won’t write any more poetry. This is over - Marina will write later. “No one sees, no one knows that I’ve been looking for a hook with my eyes for a year now... I’ve been trying on death for a year.”

In 1941, Hitler attacks Russia. This drives Marina into despair. Finding herself alone with her 15-year-old son in her arms, Marina again experiences hunger and cold. A letter from Marina has been preserved asking her to be hired as a dishwasher by the Literary Fund Council.

The hook that Marina had been looking for for a long time was found on August 31, 1941 in remote, remote Yelabuga. On the death certificate, the occupation of the deceased was listed as “evacuated.” Marina's grave is lost and unknown. However, in 1960, Marina's sister installed a cross and a tombstone, saying that claims about the loss of the grave were just speculation.

Sergei Efron's husband was shot on October 16, 1941, and his son Georgiy was killed in the war in 1944. Marina also had a younger daughter, Irina, born in 1917. She died three years later, in an orphanage, where Marina gave her up so that she would not die from hunger, which the orphanage overtook earlier than she thought. Only the daughter Ariadne survived, having gone through prisons, camps and exile, who devoted the rest of her life to collecting and publishing the literary heritage of the poetess.

In 1914, Marina Tsvetaeva met the poetess Sofia Parnok. In 1916, their relationship ended. Marina dedicated the cycle of poems “Girlfriend” to Parnok. Until now, their relationship gives rise to numerous insinuations.

- In 1990, Patriarch Alexy II performed the funeral service for Marina Tsvetaeva at the request of a group of believers, including Tsvetaeva’s sister, despite the ban on funeral services for suicides in the church.

- In 1992, Marina Tsvetaeva’s poem “To My Poems” was written on the wall of one of the buildings in the center of Leiden (Netherlands) as part of the “Wall poems” project. There are 7 Marina Tsvetaeva museums in Russia, including in Moscow, where she was born and lived, and the Memorial Complex in Yelabuga, where she died.

Writer's Awards

Bibliography

1910 - “Evening Album”

1912 - "Magic Lantern"

1913 - “Youthful Poems”, 1913-1915.

1922 - “Poems to Blok”

1922 - “The End of Casanova”

1921 - “Versts”

1921 - “Swan Camp”

1922 - “Separation”

1923 - “Craft”

1923 - “Psyche. Romance"

1924 - “Well done”

1928 - “After Russia”

collection 1940

1918 -

1918 -

"

1918 -

1918-1919 -

“Poems grow like stars and like roses,

Like beauty - unnecessary in the family.

And for crowns and apotheoses -

One answer: “Where do I get this?”

We sleep - and now, through the stone slabs,

Heavenly guest with four petals.

O world, understand! Singer - in a dream - open

The law of the star and the formula of the flower."

Marina Tsvetaeva .

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva (1892-1941) – Russian poetess, prose writer, translator, one of the largest Russian poets of the 20th century. Born on September 26 (October 8, new style) 1892 in Moscow. Her father, Ivan Vladimirovich, is a professor at Moscow University, a famous philologist and art critic; later became director of the Rumyantsev Museum and founder of the Museum of Fine Arts. Mother, Maria Main (originally from a Russified Polish-German family), was a pianist, a student of Anton Rubinstein.

Marina began writing poetry - not only in Russian, but also in French and German - at the age of six. Her mother had a huge influence on the formation of Marina’s character. She dreamed of seeing her daughter become a musician. After her mother's death from consumption in 1906, Marina and her sister Anastasia were left in the care of their father.

Tsvetaeva's childhood years were spent in Moscow and Tarusa. Due to her mother's illness, Marina lived for a long time in Italy, Switzerland and Germany. She received her primary education in Moscow, at the private women's gymnasium M. T. Bryukhonenko; continued it in boarding houses in Lausanne (Switzerland) and Freiburg (Germany). At the age of sixteen, she took a trip to Paris to attend a short course of lectures on Old French literature at the Sorbonne.

In 1910, Marina published her first collection of poems, “Evening Album,” with her own money. Her work attracted the attention of famous poets - Valery Bryusov, Maximilian Voloshin and Nikolai Gumilyov. In the same year, Tsvetaeva wrote her first critical article, “Magic in Bryusov’s Poems.” The “Evening Album” was followed two years later by a second collection, “The Magic Lantern.”

The beginning of Tsvetaeva’s creative activity is associated with the circle of Moscow symbolists. After meeting Bryusov and the poet Ellis, Tsvetaeva participated in the activities of circles and studios at the Musaget publishing house.

Tsvetaeva's early work was significantly influenced by Nikolai Nekrasov, Valery Bryusov and Maximilian Voloshin (the poetess stayed at Voloshin's house in Koktebel in 1911, 1913, 1915 and 1917).

In 1911, Tsvetaeva met Sergei Efron; in January 1912 she married him. In the same year, Marina and Sergei had a daughter, Ariadna (Alya).

In 1913, the third collection, “From Two Books,” was published.

In the summer of 1916, Tsvetaeva arrived in the city of Alexandrov, where her sister Anastasia Tsvetaeva lived with her common-law husband Mavrikiy Mints and son Andrei. In Alexandrov, Tsvetaeva wrote a series of poems (“To Akhmatova,” “Poems about Moscow,” and other poems), and literary scholars later called her stay in the city “Marina Tsvetaeva’s Alexandrov Summer.”

In 1917, Tsvetaeva gave birth to a daughter, Irina, who died of starvation in an orphanage at the age of 3 years.

The years of the Civil War turned out to be very difficult for Tsvetaeva. Sergei Efron served in the White Army. Marina lived in Moscow, on Borisoglebsky Lane. During these years, the cycle of poems “Swan Camp” appeared, imbued with sympathy for the white movement.

In 1918-1919, Tsvetaeva wrote romantic plays; The poems “Egorushka”, “The Tsar Maiden”, “On a Red Horse” were created.

In April 1920, Tsvetaeva met Prince Sergei Volkonsky.

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and her daughter Ariadna were allowed to go abroad to join her husband, who, having survived the defeat of Denikin as a white officer, had now become a student at the University of Prague. At first, Tsvetaeva and her daughter lived for a short time in Berlin, then for three years on the outskirts of Prague. The famous “Poem of the Mountain” and “Poem of the End”, dedicated to Konstantin Rodzevich, were written in the Czech Republic. In 1925, after the birth of their son George, the family moved to Paris.

In Paris, Tsvetaeva was greatly influenced by the atmosphere that developed around her due to her husband’s activities. Efron was accused of being recruited by the NKVD and participating in a conspiracy against Lev Sedov, Trotsky's son.

In May 1926, at the instigation of Boris Pasternak, Tsvetaeva began corresponding with the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who then lived in Switzerland. This correspondence ended at the end of that year with Rilke's death. Throughout the entire time spent in exile, Tsvetaeva’s correspondence with Boris Pasternak did not stop.

Most of what Tsvetaeva created in exile remained unpublished. In 1928, the poetess’s last lifetime collection, “After Russia,” was published in Paris, which included poems from 1922-1925. Later, Tsvetaeva writes about it this way: “My failure in emigration is that I am not an emigrant, that I am in spirit, that is, in air and in scope - there, there, from there...”

In 1930, a poetic cycle “To Mayakovsky” was written (on the death of Vladimir Mayakovsky), whose suicide shocked Tsvetaeva.

In contrast to her poems, which did not receive recognition among the emigrants, her prose enjoyed success, and occupied the main place in her work in the 1930s (“Emigration makes me a prose writer...”). At this time, “My Pushkin” (1937), “Mother and Music” (1935), “House at Old Pimen” (1934), “The Tale of Sonechka” (1938), and memoirs about Maximilian Voloshin (“Living about Living”) were published. , 1933), Mikhail Kuzmin (“Unearthly Evening”, 1936), Andrei Bel (“Captive Spirit”, 1934), etc.

Since the 1930s, Tsvetaeva and her family lived in almost poverty.

On March 15, 1937, Ariadna left for Moscow, the first in her family to have the opportunity to return to her homeland. On October 10 of the same year, Efron fled from France, having become involved in a contracted political murder (in order to return to the USSR, he became an NKVD agent abroad).

In 1939, Tsvetaeva returned to the USSR following her husband and daughter. Upon arrival, she lived at the NKVD dacha in Bolshevo (now the Museum-Apartment of M. I. Tsvetaeva in Bolshevo). On August 27, daughter Ariadne was arrested, and on October 10, Efron. In August 1941, Sergei Yakovlevich was shot; Ariadne was rehabilitated in 1955 after fifteen years of repression.

During this period, Tsvetaeva practically did not write poetry, doing translations.

The war found Tsvetaeva translating Federico Garcia Lorca. Work was interrupted. On August 8, Tsvetaeva and her son left for evacuation by ship; On the 18th she arrived together with several writers in the town of Elabuga on the Kama. In Chistopol, where mostly evacuated writers were located, Tsvetaeva received consent to register and left a statement: “To the council of the Literary Fund. I ask you to hire me as a dishwasher in the Literary Fund's opening canteen. August 26, 1941." But she was not given such a job either: the council of writers’ wives considered that she might turn out to be a German spy. On August 28, she returned to Yelabuga with the intention of moving to Chistopol.

Pasternak, seeing her off for evacuation, gave her a rope for her suitcase, not suspecting what terrible role this rope was destined to play. Unable to withstand the humiliation, on August 31, 1941, Tsvetaeva hanged herself with the very rope that Pasternak gave her.

Marina Tsvetaeva was buried on September 2, 1941 at the Peter and Paul Cemetery in Elabuga. The exact location of her grave is unknown.

TSVETAEVA, MARINA IVANOVNA(1892–1941), Russian poet.

Born on September 26 (October 9) in Moscow. Tsvetaeva's parents were Ivan Vladimirovich Tsvetaev and Maria Aleksandrovna Tsvetaeva (née Main). His father, a classical philologist, professor, headed the department of history and theory of art at Moscow University, and was the curator of the department of fine arts and classical antiquities at the Moscow Public and Rumyantsev Museums. In 1912, on his initiative, the Alexander III Museum was opened in Moscow (now the A.S. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts). In her father, Tsvetaeva valued devotion to her own aspirations and ascetic work, which, as she claimed, she inherited from him. Much later, in the 1930s, she dedicated several memoir essays to her father ( Alexander III Museum, Laurel wreath, Museum opening, Father and his museum).

Maria Alexandrovna died in 1906, when Marina was still a young girl. The daughter retained an enthusiastic admiration for her mother’s memory. Marina Ivanovna dedicated essays and memoirs written in the 1930s to her mother ( Mother and music, Mother's Tale).

Despite her spiritually close relationship with her mother, Tsvetaeva felt lonely and alienated in her parents’ home. She deliberately closed her inner world both from her sister Asya and from her half-brother and sister, Andrei and Valeria. Even with Maria Alexandrovna there was no complete understanding. Young Marina lived in a world of read books and sublime romantic images.

The family spent the winter season in Moscow, the summer in the city of Tarusa, Kaluga province. The Tsvetaevs also traveled abroad. In 1903, Tsvetaeva studied at a French boarding school in Lausanne (Switzerland), in the fall of 1904 - in the spring of 1905 she studied with her sister at a German boarding school in Freiburg (Germany), in the summer of 1909 she went alone to Paris, where she attended a course in ancient French literature at the Sorbonne.

According to her own recollections, Tsvetaeva began writing poetry at the age of six. In 1906–1907 she wrote a novella (or short story) Fourth, in 1906 translated into Russian the drama of the French writer E. Rostand Eaglet, dedicated to the tragic fate of Napoleon’s son (neither the story nor the translation of the drama has survived). In literature, she was especially fond of the works of A.S. Pushkin and the works of German romantics, translated by V.A. Zhukovsky.

Tsvetaeva’s works appeared in print in 1910, when she published her first book of poems at her own expense - Evening album. Ignoring the accepted rules of literary behavior, Tsvetaeva resolutely demonstrated her own independence and unwillingness to conform to the social role of a “writer.” She saw writing poetry not as a professional activity, but as a private matter and direct self-expression.

Poetry Evening album they were distinguished by their “homely” quality, they varied such motives as the awakening of a young girl’s soul, the happiness of a trusting relationship connecting the lyrical heroine and her mother, the joys of impressions from the natural world, first love, friendship with fellow high school students. Chapter Love composed poems addressed to V.O. Nylender, with whom Tsvetaeva was then fascinated. The poems combined themes and moods inherent in children's poetry with virtuoso poetic technique.

Poeticization of everyday life, autobiographical nudity, installation on the diary principle, characteristic of Evening album, inherited by the poems that made up Tsvetaeva’s second book, Magic lantern (1912).

Evening album was very well received by critics: the novelty of the tone and the emotional authenticity of the book were noted by V.Ya. Bryusov, M.A. Voloshin, N.S. Gumilyov, M.S. Shaginyan. Magic lantern was perceived as a relative failure, as a repetition of the original features of the first book, devoid of poetic novelty. Tsvetaeva herself also felt that she was beginning to repeat herself. In 1913 she released a new collection - From two books. When compiling her third book, she very strictly selected the texts: out of two hundred and thirty-nine poems included in Evening album And Magic lantern, only forty were reprinted. Such exactingness testified to the poetic growth of the author. At the same time, Tsvetaeva still shunned literary circles, although she met or became friends with some writers and poets (one of her closest friends was M.A. Voloshin, to whom Tsvetaeva later dedicated a memoir essay Living things about living things, 1933). She did not recognize herself as a writer. Poetry remained for her a private matter and a high passion, but not a professional matter.

In the winter of 1910–1911, M.A. Voloshin invited Marina Tsvetaeva and her sister Anastasia (Asya) to spend the summer of 1911 in Koktebel, where he lived. In Koktebel, Tsvetaeva met Sergei Yakovlevich Efron.

In Sergei Efron, Tsvetaeva saw the embodied ideal of nobility, chivalry and, at the same time, defenselessness. Love for Efron was for her admiration, spiritual union, and almost maternal care. I defiantly wear his ring / - Yes, in Eternity - a wife, not on paper. – / His overly narrow face / Like a sword, Tsvetaeva wrote about Efron, taking love as an oath: In his face I am faithful to chivalry. Tsvetaeva perceived her meeting with him as the beginning of a new, adult life and as finding happiness: Real, first happiness / Not from books! In January 1912, the wedding of Tsvetaeva and Sergei Efron took place. On September 5 (old style), their daughter Ariadne (Alya) was born.

Throughout 1913–1915, a gradual change in Tsvetaeva’s poetic manner took place: the place of a touching and cozy children’s life is taken by the aestheticization of everyday details (for example, in the cycle Girlfriend, 1914–1915, addressed to the poetess S.Ya.Parnok), and an ideal, sublime image of antiquity (poems Generals of the twelfth year, 1913, Grandma, 1914, etc.). Tsvetaeva overcame the danger of turning into an “aesthetic” poetess and confining herself to a narrow circle of themes and stylistic clichés in her lyric poetry of 1916. From that time on, her poems became more diverse in metric and rhythmic terms (she mastered the dolnik and tonic verse, deviated from the principle of equal stress between lines ); the poetic vocabulary is expanding to include colloquial vocabulary, imitation of the style of folk poetry and neologisms. The diary and confessional nature of early creativity are replaced by role-playing lyrics, in which poetic “doubles” become a means of expressing the author’s “I”: Carmen (cycle Don Juan, 1917), Manon Lescaut is the heroine of the 18th century French novel of the same name. (poem Chevalier de Grieux! - In vain..., 1917). In the poems of 1916, reflecting Tsvetaeva’s romance with O.E. Mandelstam (1915–early 1916), Tsvetaeva associates herself with Marina Mnishek, the Polish wife of the impostor Grigory Otrepiev (False Dmitry I), and O.E. Mandelstam - at the same time with the real Tsarevich Dimitri , and with the impostor Otrepyev. Mandelstam dedicated several poems to Tsvetaeva: On sledges lined with straw..., In the discordant voices of the girls’ choir..., Not believing Sunday's miracle.... (Later Tsvetaeva described her acquaintance and communication with the poet in an essay The story of one dedication, 1931).

Terrible and tragic themes penetrate Tsvetaeva’s poetic world, and the lyrical heroine is endowed with traits of holiness, compared to the Mother of God, and demonic, dark traits, and is called a “warlock”). In 1915–1916, Tsvetaeva’s individual poetic symbolism, her “personal mythology,” took shape. It is characterized by the heroine’s “I” as one that absorbs everything into itself, endowed with a “shell” nature ( Calling you, praising you, I am only / The shell where the ocean has not yet fallen silent- poem Black, like a pupil, sucking... from the cycle Insomnia, 1916); the heroine’s detachment from her own flesh, the “sleep” of the body, the symbolic identification of the “I” with the vineyard and the vine ( Not by the windy wind - until - autumn..., 1916); endowing the heroine with the gift of flight, identifying her hands with wings. These features of poetics will be preserved in Tsvetaeva’s poems of later times.

Tsvetaeva’s characteristic demonstrative independence and sharp rejection of generally accepted ideas and behavioral norms manifested themselves not only in communication with other people (to them Tsvetaeva’s incontinence often seemed rude and bad manners), but also in assessments and actions related to politics. Tsvetaeva perceived the First World War (in the spring of 1915, her husband, Sergei Efron, leaving his studies at the university, became a brother of mercy on a military ambulance train) as an explosion of hatred against Germany, dear to her heart since childhood. She responded to the war with poems that were sharply dissonant with the patriotic and chauvinistic sentiments of the end of 1914: You are given over to the world to be persecuted, / And your enemies have no count, / Well, how can I leave you? / Well, how can I betray you? (Germany, 1914). She welcomed the February Revolution of 1917, as did her husband, whose parents (who died before the revolution) were Narodnaya Volya revolutionaries. She perceived the October Revolution as the triumph of destructive despotism. Sergei Efron sided with the Provisional Government and took part in the Moscow battles, defending the Kremlin from the Red Guards. The news of the October Revolution found Tsvetaeva in Crimea, visiting Voloshin. Soon her husband arrived here too. On November 25, 1917, she left Crimea for Moscow to pick up her children - Alya and little Irina, born in April of this year. Tsvetaeva intended to return with her children to Koktebel, to Voloshin, Sergei Efron decided to go to the Don to continue the fight against the Bolsheviks there. It was not possible to return to Crimea: insurmountable circumstances and the fronts of the Civil War separated Tsvetaeva from her husband and from Voloshin. She never saw the Voloshins again. Sergei Efron fought in the ranks of the White Army, and Tsvetaeva, who remained in Moscow, had no news of him. In hungry and impoverished Moscow in 1917–1920, she wrote poems glorifying the sacrificial feat of the White Army: White Guard, your path is high: / To the black barrel - chest and temple; Storms-blizzards, whirlwinds-winds nurtured you, / And you will remain in song - white swans! By the end of 1921 these poems were combined into a collection Swan camp, prepared for publication. (The collection was not published during Tsvetaeva’s lifetime; it was first published in the West in 1957). Tsvetaeva publicly and boldly read these poems in Bolshevik Moscow. Tsvetaeva’s glorification of the white movement had not political, but spiritual and moral reasons. She was in solidarity not with the triumphant victors - the Bolsheviks, but with the doomed vanquished. To the poem Posthumous March(1922), dedicated to the death of the Volunteer Army, she chose the epigraph Volunteering is the good will to die. In May - July 1921 she wrote a cycle Parting addressed to her husband.

She and the children had difficulty making ends meet and were starving. At the beginning of the winter of 1919–1920, Tsvetaeva sent her daughters to an orphanage in Kuntsevo. Soon she learned about the serious condition of her daughters and took home the eldest, Alya, to whom she was attached as a friend and whom she loved frantically. Tsvetaeva’s choice was explained both by the inability to feed both of them, and by her indifferent attitude towards Irina. At the beginning of February 1920, Irina died. Her death is reflected in the poem Two hands, easily lowered...(1920) and in the lyric cycle Parting (1921).

Tsvetaeva combined lyrics from 1917–1920 into a collection Versts, published in two editions in Moscow (1921, 1922).

Tsvetaeva, like many of her literary contemporaries, perceived the coming NEP sharply negatively, as a triumph of bourgeois “satiety”, self-satisfied and selfish mercantilism.

On July 11, 1921, she received a letter from her husband, who had evacuated with the remnants of the Volunteer Army from Crimea to Constantinople. Soon he moved to the Czech Republic, to Prague. After several grueling attempts, Tsvetaeva received permission to leave Soviet Russia and on May 11, 1922, together with her daughter Alya, left her homeland.

On May 15, 1922, Marina Ivanovna and Alya arrived in Berlin. Tsvetaeva remained there until the end of July, where she became friends with the symbolist writer Andrei Bely, who temporarily lived there. In Berlin, she publishes a new collection of poems - Craft(published in 1923) – and a poem Tsar-Maiden. Sergei Efron came to his wife and daughter in Berlin, but soon returned to the Czech Republic, to Prague, where he studied at Charles University and received a scholarship allocated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Czechoslovakia. Tsvetaeva and her daughter came to her husband in Prague on August 1, 1922. She spent more than four years in the Czech Republic. They could not afford to rent an apartment in the Czech capital, and the family first settled in the suburb of Prague - the village of Horni Mokropsy. Later they managed to move to Prague, then Tsvetaeva and her daughter and Efron again left the capital and lived in the village of Vshenory near Gorni Mokropsy. In Vshenory on February 1, 1925, her long-awaited son was born, named Georgy (home name - Moore). Tsvetaeva adored him. The desire to do everything possible for the happiness and well-being of his son was perceived by the growing Moore as alienated and selfish; wittingly and unwittingly, he played a tragic role in the fate of his mother.

In Prague, Tsvetaeva for the first time established permanent relationships with literary circles, with publishing houses and magazine editors. Her works were published on the pages of the magazines “The Will of Russia” and “In Our Own Ways”, Tsvetaeva performed editorial work for the almanac “Ark”.

The last years spent in her homeland and the first years of emigration were marked by new features in Tsvetaeva’s understanding of the relationship between poetry and reality; the poetics of her poetic works also underwent changes. She now perceives reality and history as alien, hostile to poetry. The genre range of Tsvetaeva’s creativity is expanding: she writes dramatic works and poems. In the poem Tsar Maiden(September 1920) Tsvetaeva reinterprets the plot of the folk tale about the love of the Tsar Maiden and the Tsarevich into a symbolic story about the heroine and hero’s insight into another world (“heavenly seas”), about an attempt to unite love and creativity - about an attempt that in earthly existence is doomed to failure. Tsvetaeva turned to another folk tale, telling about a ghoul who took possession of a girl, in her poem M?dolets(1922). She depicts the passion-obsession of the heroine Marusya with love for the Well done Ghoul; Marusya's love is disastrous for her loved ones, but for herself it opens the way to posthumous existence, to eternity. Love is interpreted by Tsvetaeva as a feeling that is not so much earthly as transcendental, dual (disastrous and salutary, sinful and beyond jurisdiction).

In 1924 Tsvetaeva created Poem of the Mountain, completes Poem of the End. The first poem reflects Tsvetaeva’s romance with a Russian emigrant, an acquaintance of her husband K.B. Rodzevich, and the second reflects their final break. Tsvetaeva perceived love for Rodzevich as a transformation of the soul, as its salvation. Rodzevich recalled this love this way: “We got along in character<…>- give yourself completely. There was a lot of sincerity in our relationship, we were happy.” Tsvetaeva’s exactingness towards her lover and her inherent awareness of the short duration of absolute happiness and the inseparability of lovers led to a separation that occurred on her initiative.

IN Poem of the Mountain The “lawless” passion of the hero and heroine is contrasted with the dull existence of the Prague inhabitants living on the plain. The mountain (its prototype is the Prague Petrin Hill, next to which Tsvetaeva lived for some time) symbolizes love in its hyperbolic grandeur, and the height of the spirit, and grief, and the place of the promised meeting, the highest revelation of the spirit:

If you tremble, the mountains will fall off your shoulders,

And the soul is grief.

Let me sing about grief:

About my grief.

<..>

Oh, far from basic

Heaven for drafts!

The mountain knocked us down

Attracted: lie down!

Biblical implications Poems of the End- crucifixion of Christ; symbols of parting are a bridge and a river (it corresponds to the real Vltava River), separating the heroine and the hero.

The motives of parting, loneliness, misunderstanding are constant in Tsvetaeva’s lyrics of these years: cycles Hamlet(1923, later divided into separate poems), Phaedra (1923), Ariadne(1923). Thirst and impossibility of meeting, the union of poets as a love union, the fruit of which will be living child: / Song– leitmotifs of the cycle Wires, addressed to B.L. Pasternak. The telegraph wires stretching between Prague and Moscow become a symbol of the connection of those separated:

A string of singing piles,

propping up the Empyrean,

I'm sending you my share

Ashes of the last.

Along the alley

Sighs - wire to the post -

Telegraph: lyu - yu - blue...

Poetic dialogue and correspondence with Pasternak, with whom Tsvetaeva was not closely acquainted before leaving Russia, became for Tsvetaeva in exile the friendly communication and love of two spiritually related poets. In Pasternak's three lyric poems addressed to Tsvetaeva, there are no love motives; these are appeals to a friend-poet. Tsvetaeva served as the prototype for Maria Ilyina from Pasternak’s novel in verse Spectorsky. Tsvetaeva, hoping as if for a miracle, was waiting for a personal meeting with Pasternak; but when he visited Paris with a delegation of Soviet writers in June 1935, their meeting turned into a conversation between two people spiritually and psychologically distant from each other.

In the lyrics of the Prague period, Tsvetaeva also addresses the theme of overcoming the carnal, material principle, escape, escaping from matter and passions into the world of spirit, detachment, non-existence, which has become dear to her: After all, you won’t worry! I won't get carried away! / No hands after all! No lips to fall / With your lips! – With immortality, a snake bite / A woman’s passion ends! (Eurydice to Orpheus, 1923); Or maybe the best victory / Over time and gravity is / To pass so as not to leave a trace, / To pass so as not to leave a shadow // On the walls... (Sneak..., 1923).

In the second half of 1925, Tsvetaeva made the final decision to leave Czechoslovakia and move to France. Her action was explained by the difficult financial situation of the family; she believed that she could better arrange herself and her loved ones in Paris, which was then becoming the center of Russian literary emigration. November 1, 1925 Tsvetaeva and her children arrived in the French capital; Sergei Efron also moved there by Christmas.

In Paris in November 1925, she completed the poem (the author's title is “lyrical satire”) Pied Piper based on the medieval legend about a man who saved the German city of Gammeln from rats by luring them out with the sounds of his wonderful pipe; when the stingy inhabitants of Hammel refused to pay him, he brought out their children, playing on the same pipe, and took them to the mountain, where they were swallowed up by the opening earth. Pied Piper was published in the Prague magazine “Will of Russia”. In Tsvetaeva’s interpretation, the rat catcher personifies the creative, magically powerful principle; rats are associated with the Bolsheviks, who were previously aggressive and hostile to the bourgeoisie, and then turned into the same ordinary people as their recent enemies; Hamelians are the embodiment of a vulgar, bourgeois spirit, self-satisfaction and narrow-mindedness.

In France, Tsvetaeva created several more poems. Poem New Year's(1927) - a lengthy epitaph, a response to the death of the German poet R.-M. Rilke, with whom she and Pasternak corresponded. Poem of Air(1927), is an artistic reimagining of the non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean made by the American aviator C. Lindbergh. Tsvetaeva’s pilot’s flight is both a symbol of creative soaring and an allegorical, encrypted image of a person dying. Tragedy was also written Phaedra(published in 1928 in the Parisian magazine “Modern Notes”).

In France, cycles dedicated to poetry and poets were created Mayakovsky(1930, response to the death of V.V. Mayakovsky), Poems to Pushkin (1931), Tombstone(1935, response to the tragic death of the emigrant poet N.P. Gronsky), Poems for an orphan(1936, addressed to the emigrant poet A.S. Steiger). Creativity as hard labor, as duty and liberation - the motive of the cycle Table(1933). The antithesis of vain human life and divine secrets and harmony of the natural world is expressed in poems from the cycle Bush(1934). In the 1930s, Tsvetaeva often turned to prose: autobiographical works, essays about Pushkin and his works ( My Pushkin, published in No. 64 for 1937 of the Parisian magazine “Modern Notes”), Pushkin and Pugachev(published in No. 2, 1937, of the Paris-Shanghai magazine “Russian Notes”).

Moving to France did not make life easier for Tsvetaeva and her family. Sergei Efron, impractical and not adapted to the hardships of life, earned little; Only Tsvetaeva herself could earn a living through literary work. However, in the leading Parisian periodicals (in Sovremennye Zapiski and Latest News), Tsvetaeva was published little; her texts were often edited. For all her Parisian years, she was able to release only one collection of poems - After Russia(1928). The emigrant literary environment, predominantly focused on the revival and continuation of the classical tradition, was alien to Tsvetaeva’s emotional expression and hyperbolism, which was perceived as hysteria. The dark and complex avant-garde poetics of emigrant poems did not meet with understanding. Leading emigrant critics and writers (Z.N. Gippius, G.V. Adamovich, G.V. Ivanov and others) assessed her work negatively. The high appreciation of Tsvetaev's works by the poet and critic V.F. Khodasevich and the critic D.P. Svyatopolk-Mirsky, as well as the sympathy of the younger generation of writers (N.N. Berberova, Dovid Knut, etc.) did not change the general situation. Tsvetaeva’s rejection was aggravated by her complex character and her husband’s reputation (Sergei Efron had been applying for a Soviet passport since 1931, expressed pro-Soviet sympathies, and worked in the Homecoming Union). He began to collaborate with Soviet intelligence services. The enthusiasm with which Tsvetaeva greeted Mayakovsky, who arrived in Paris in October 1928, was perceived by conservative emigrant circles as evidence of the pro-Soviet views of Tsvetaeva herself (in fact, Tsvetaeva, unlike her husband and children, did not have any illusions about the regime in the USSR and was pro-Soviet was not configured).

In the second half of the 1930s, Tsvetaeva experienced a deep creative crisis. She almost stopped writing poetry (one of the few exceptions is the cycle Poems to the Czech Republic(1938–1939) - a poetic protest against Hitler's seizure of Czechoslovakia. Rejection of life and time is the leitmotif of several poems written in the mid-1930s: Solitude: go away, // Life!(Solitude: go away..., 1934), My age is my poison, my age is my harm, / My age is my enemy, my age is hell (I didn’t think about the poet..., 1934). Tsvetaeva had a serious conflict with her daughter, who insisted, following her father, on leaving for the USSR; the daughter left her mother's house. In September 1937, Sergei Efron was involved in the murder by Soviet agents of I. Reiss, also a former agent of the Soviet secret services, who tried to leave the game. (Tsvetaeva was not aware of her husband’s role in these events). Soon Efron was forced to hide and flee to the USSR. Following him, his daughter Ariadne returned to her homeland. Tsvetaeva remained in Paris alone with her son, but Moore also wanted to go to the USSR. There was no money for the life and education of her son, Europe was threatened by war, and Tsvetaeva was afraid for Moore, who was already almost an adult. She also feared for her husband’s fate in the USSR. Her duty and desire was to unite with her husband and daughter. On June 12, 1939, on a ship from the French city of Le Havre, Tsvetaeva and Moore sailed to the USSR, and on June 18 they returned to their homeland.

In their homeland, Tsvetaev and his family first lived at the state dacha of the NKVD in Bolshevo, near Moscow, provided to S. Efron. However, soon both Efron and Ariadne were arrested (S. Efron was later shot). From that time on, she was constantly visited by thoughts of suicide. After this, Tsvetaeva was forced to wander. For six months, before receiving temporary (for a period of two years) housing in Moscow, she settled with her son in the house of writers in the village of Golitsyn near Moscow. Meetings with A. Akhmatova and B. Pasternak did not live up to Tsvetaeva’s expectations. The functionaries of the Writers' Union turned away from her as the wife and mother of “enemies of the people.” The collection of poems she prepared in 1940 was not published. There was a catastrophic lack of money (Tsvetaeva earned her small funds through transfers). She was forced to accept the help of few friends.

Shortly after the start of the Great Patriotic War, on August 8, 1941, Tsvetaeva and her son were evacuated from Moscow and ended up in the small town of Elabuga. There was no work in Yelabuga. From the leadership of the Writers' Union, evacuated to the neighboring city of Chistopol, Tsvetaeva asked permission to settle in Chistopol and a position as a dishwasher in the writers' canteen. Permission was given, but there was no space in the canteen, since it had not yet opened. After returning to Yelabuga, Tsvetaeva had a quarrel with her son, who, apparently, reproached her for their difficult situation. The next day, August 31, 1941, Tsvetaeva hanged herself. The exact place of her burial is unknown.

Publications by M. Tsvetaeva: Unreleased. Family: History in Letters/ Comp. and comment. E.B.Korkina. M., 1999; Unreleased. Summary notebooks/ Prepare text and notes E.B. Korkina and I.D. Shevelenko. M., 1997; Poems and poems/ Ed. E.B.Korkina. L., 1990 (Poet's book, Big series)

Andrey Ranchin

Literature:

Farino J. Mythologism and theologism of Tsvetaeva. Wien, 1985 (Wiener Slawistischer Almanach. Sonderband 18)

Elnitskaya S. The poetic world of Tsvetaeva: The conflict between the lyrical hero and reality. Wien, 1990 (Wiener Slawistischer Almanach. Sonderband 30)

Losskaya V. Marina Tsvetaeva in life: Unpublished memories of contemporaries. M., 1992

Gasparov M.L. Marina Tsvetaeva: from the poetics of everyday life to the poetics of words // Gasparov M.L. Featured Articles. M., 1995 (New Literary Review. Scientific Library. Issue 2.)

Kudrova I . Death of Marina Tsvetaeva. M., 1995

Kudrova I. After Russia. Marina Tsvetaeva: Years of foreign lands. M., 1997

Sahakyants A . Marina Tsvetaeva: Life and creativity. M., 1997

Brodsky about Tsvetaeva: interview, essay. M., 1998

Belkina M. Crossing of destinies. Ed. 3rd, revised and additional M., 1999

Kling O.A .

The poetic world of M.I. Tsvetaeva. M., 2001

Marina Tsvetaeva in the memoirs of contemporaries: The birth of a poet. M., 2002

Marina Tsvetaeva in the memoirs of contemporaries: Years of emigration. M., 2002

Marina Tsvetaeva in the memoirs of contemporaries: Returning to her homeland. Comp., prep. text, intro. article, note L. Mnukhin, L. Turchinsky. M., 2002

Schweitzer V. Marina Tsvetaeva. M., 2002 (Series “Life of Remarkable People”)

Shevelenko I. Tsvetaeva’s literary path: Ideology – poetics – author’s identity in the context of the era. M., 2002 (New Literary Review. Scientific Library. Issue 38).

Marina Tsvetaeva was born in Moscow on September 26 (October 8), 1892. Her father was a university professor, her mother a pianist. It is worth briefly noting that Tsvetaeva’s biography was replenished with her first poems at the age of six.

She received her first education in Moscow at a private girls' gymnasium, then studied in boarding schools in Switzerland, Germany, and France.

After the death of her mother, Marina and her brother and two sisters were raised by their father, who tried to give the children a good education.

The beginning of a creative journey

Tsvetaeva's first collection of poems was published in 1910 (“Evening Album”). Even then, famous people - Valery Bryusov, Maximilian Voloshin and Nikolai Gumilyov - drew attention to Tsvetaeva’s work. Their work and the works of Nikolai Nekrasov significantly influenced the early work of the poetess.

In 1912, she published her second collection of poems, The Magic Lantern. These two collections by Tsvetaeva also included poems for children: “So,” “In the classroom,” “On Saturday.” In 1913, the poetess’s third collection, entitled “From Two Books,” was published.

During the Civil War (1917-1922), for Tsvetaeva, poetry was a means of expressing sympathy. In addition to poetry, she writes plays.

Personal life

In 1912, she married Sergei Efron, and they had a daughter, Ariadne.

In 1914, Tsvetaeva met the poetess Sofia Parnok. Their romance lasted until 1916. Tsvetaeva dedicated a cycle of her poems called “Girlfriend” to her. Then Marina returned to her husband.

Marina's second daughter, Irina, died at the age of three. In 1925, son George was born.

Life in exile

In 1922, Tsvetaeva moved to Berlin, then to the Czech Republic and Paris. Tsvetaeva’s creativity of those years includes the works “Poem of the Mountain”, “Poem of the End”, “Poem of the Air”. Tsvetaeva’s poems from 1922-1925 were published in the collection “After Russia” (1928). However, the poems did not bring her popularity abroad. It was during the period of emigration that prose received great recognition in the biography of Marina Tsvetaeva.

Tsvetaeva writes a series of works dedicated to famous and significant people:

- in 1930, the poetic cycle “To Mayakovsky” was written, in honor of the famous Vladimir Mayakovsky, whose suicide shocked the poetess;

- in 1933 - “Living about Living”, memories of Maximilian Voloshin

- in 1934 - “Captive Spirit” in memory of Andrei Bely

- in 1936 - “An Unearthly Evening” about Mikhail Kuzmin

- in 1937 - “My Pushkin”, dedicated to Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin

Return to homeland and death

Having lived the 1930s in poverty, in 1939 Tsvetaeva returned to the USSR. Her daughter and husband are arrested. Sergei was shot in 1941, and his daughter was rehabilitated 15 years later.

During this period of her life, Tsvetaeva almost did not write poetry, but only did translations.

On August 31, 1941, Tsvetaeva committed suicide. The great poetess was buried in the city of Elabuga at the Peter and Paul Cemetery.

The Tsvetaeva Museum is located on Sretenka Street in Moscow, also in Bolshevo, Aleksandrov, Vladimir Region, Feodosia, Bashkortostan. The monument to the poetess was erected on the banks of the Oka River in the city of Tarusa, as well as in Odessa.

Chronological table

Other biography options

- Marina Tsvetaeva began writing her first poems as a child. And she did this not only in Russian, but also in French and German. She knew languages very well, because her family often lived abroad.

- She met her husband by chance while relaxing by the sea. Marina always believed that she would fall in love with the person who gave her the stone she liked. Her future husband, without knowing it, gave Tsvetaeva a carnelian he found on the beach on the very first day they met.

- During the Second World War, Tsvetaeva and her son were evacuated to Elabuga (Tatarstan). While helping Marina pack her suitcase, her friend, Boris Pasternak, joked about the rope he had taken to tie up the suitcase (that it was strong, even if you hang yourself). It was on this ill-fated rope that the poetess hanged herself.

- see all

(1892 1941)

Russian poetess. The daughter of a scientist, specialist in the field of ancient history, epigraphy and art, Ivan Vladimirovich Tsvetaev. Romantic maximalism, motives of loneliness, the tragic doom of love, rejection of everyday life (collections "Versta", 1921, "Craft", 1923, "After Russia", 1928; satirical poem "The Pied Piper", 1925, "Poem of the Mountain", "Poem of the End" ", both 1926). Tragedies ("Phaedra", 1928). Intonation-rhythmic expressiveness, paradoxical metaphor. Essay prose (“My Pushkin”, 1937; memories of A. Bely, V. Ya. Bryusov, M. A. Voloshin, B. L. Pasternak, etc.). In 1922 39 in exile. She committed suicide.

Biography

Born on September 26 (October 8, n.s.) in Moscow into a highly cultured family. Father, Ivan Vladimirovich, a professor at Moscow University, a famous philologist and art critic, later became the director of the Rumyantsev Museum and the founder of the Museum of Fine Arts (now the State Museum of Fine Arts named after A. S. Pushkin). Mother came from a Russified Polish-German family and was a talented pianist. She died in 1906, leaving two daughters in the care of her father.

Tsvetaeva's childhood years were spent in Moscow and at her dacha in Tarusa. Having begun her education in Moscow, she continued it in boarding houses in Lausanne and Freiburg. At the age of sixteen, she made an independent trip to Paris to take a short course in the history of Old French literature at the Sorbonne.

She began writing poetry at the age of six (not only in Russian, but also in French and German), publishing at sixteen, and two years later, secretly from her family, she released the collection “Evening Album,” which was noticed and approved by such discerning critics as like Bryusov, Gumilev and Voloshin. From the first meeting with Voloshin and a conversation about poetry, their friendship began, despite the significant difference in age. She visited Voloshin many times in Koktebel. Collections of her poems followed one after another, invariably attracting attention with their creative originality and originality. She did not join any of the literary movements.

In 1912, Tsvetaeva married Sergei Efron, who became not only her husband, but also her closest friend.

In 1912, Tsvetaeva married Sergei Efron, who became not only her husband, but also her closest friend.

The years of the First World War, revolution and civil war were a time of rapid creative growth for Tsvetaeva. She lived in Moscow, wrote a lot, but almost never published. She did not accept the October Revolution, seeing in it an uprising of “satanic forces.” In the literary world, M. Tsvetaeva still stood apart.

In May 1922, she and her daughter Ariadne were allowed to go abroad to join her husband, who, having survived the defeat of Denikin as a white officer, now became a student at the University of Prague. At first, Tsvetaeva and her daughter lived for a short time in Berlin, then for three years on the outskirts of Prague, and in November 1925, after the birth of their son, the family moved to Paris. Life was an emigrant, difficult, poor. It was beyond our means to live in the capitals; we had to settle in the suburbs or nearby villages.

Tsvetaeva’s creative energy, no matter what, did not weaken: in 1923 in Berlin, the Helikon publishing house published the book “The Craft,” which was highly praised by critics. In 1924, during the Prague period, the poems “Poem of the Mountain”, “Poem of the End”. In 1926 she finished the poem “The Pied Piper,” which she began in the Czech Republic, and worked on the poems “From the Sea,” “The Poem of the Staircase,” “The Poem of the Air,” and others. Most of what she created remained unpublished: if at first the Russian emigration accepted Tsvetaeva as one of their own, then very Soon her independence, her uncompromisingness, her obsession with poetry define her complete loneliness. She did not take part in any poetic or political movements. She has “no one to read, no one to ask, no one to rejoice with,” “alone all her life, without books, without readers, without friends...”. The last collection of his lifetime was published in Paris in 1928 “After Russia”, which included poems written in 1922 1925.

By the 1930s, the line separating her from the white emigration seemed clear to Tsvetaeva: “My failure in emigration is that I am not an emigrant, that I am in spirit, i.e. by air and by scope there, there, from there...” In 1939, she restored her Soviet citizenship and, following her husband and daughter, returned to her homeland. She dreamed that she would return to Russia as a “welcome and welcome guest.” But this did not happen: the husband and daughter were arrested, sister Anastasia was in the camp. Tsvetaeva still lived alone in Moscow, somehow getting by with translations. The outbreak of war and evacuation brought her and her son to Yelabuga. Exhausted, unemployed and lonely, the poet committed suicide on August 31, 1941.