The history of the widespread use of the method of winter route recording of game animals (WRM) in the RSFSR began in 1962 with the organization of the Biological Survey Group at the Oksky State Reserve under the leadership of V.P. Teplova. S.G. took the most active part in the development of the methodology. Priklonsky, who in 1972 published “Instructions for winter route registration of game animals” (“Kolos”, 1972).

From the very beginning, the development of the method was focused on recording animals over large areas (Priklonsky, 1965, 1969, 1973, etc.). It was the formulation “counting animals over large areas” that formed the names of three All-Union meetings on this topic (1966, 1969, 1973).

A little history

Accounting using the ZMU method was carried out first in 12 central regions of European Russia, then in 40 regions and republics of the European part of the RSFSR. In the 60s, intensive research was carried out on the method, the theoretical accuracy of the Formozov-Malyshev-Pereleshin formula was studied, its accuracy was proven (Priklonsky, 1965, 1969, 1973; Gusev, 1965, 1966; Smirnov, 1969 and many others).

In those same years, the Oksky Nature Reserve was transferred from the Main Hunting Office of the RSFSR to the subordination of the Main Nature Protection Department of the USSR, and therefore the RSFSR was left without a reliable information center on the hunting resources of the republic. For this reason, the Main Hunting Committee of the RSFSR in 1968 set the most important task for the created subordinate Central Research Laboratory: “Development of the scientific foundations of the State Service for Registration of Hunting Resources of the RSFSR.”

Intensive methodological and organizational developments were carried out, as a result of which such a public service was created in 1979 (Gosokhotuchet of the RSFSR). In 1980, the Main Hunting Agency of the RSFSR published “Methodological instructions for organizing and conducting winter route registration of game animals in the RSFSR” (Priklonsky, Kuzyakin, 1980). They significantly expanded the organizational foundations of the ZMU, slightly clarified the methodological foundations of the previous “Instructions”, without disturbing the continuity in the methodology, which is very important for obtaining comparable accounting results over a long period of time. The effects of the technique were extended to almost the entire territory of Russia, with the exception of the tundra and southern snowless regions.

Despite the simplicity of the ZMU methodology, the Russian State Hunting and Accounting Committee was faced with the task of further simplifying it. However, there was nowhere to simplify further, and in 1990 new “Methodological instructions...” were published (Kuzyakin, Chelintsev, Lomanov, 1990) with very minor changes that did not violate the continuity of the methodology and the comparability of accounting results. These guidelines are still relevant today.

Why do we need change?

However, in the second half of the 2000s, the Hunting Department, first within the framework of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Russian Federation, then as part of the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation, due to the unprecedented turnover of management personnel, without proper research, without a proper analysis of the experience of conducting wild harvesting in Russia, began to make changes to the harvesting methodology. First, “Methodological recommendations for organizing, conducting and processing data from winter route census of game animals in Russia (with algorithms for calculating numbers)” were published (Mirutenko, Lomanova, Bersenev et al., Rosinformagrotech, 2009). Despite our protests, they included some methodological errors, which, in our opinion, did not greatly affect the consistency of the accounting results.

The itch of the need for change haunted the leadership of the Hunting Department of the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation. Over the past two years, several new methods, instructions and regulations have been published, which have brought the methodology and organizational basis for carrying out health care in Russia to the point of complete absurdity. Let's look at this in more detail.

First of all, is the ZMU technique suitable for small areas (game reserve, municipality, nature reserve, or, as the illiterate now say, “hunting ground”)? Or is it only suitable for large territories (subject of the Federation, large parts of large subjects)? The whole point is the volume of accounting material collected. It should be determined by relative statistical accounting errors.

Let us clarify that a statistical error is not an actual accounting error, which cannot be determined, but only arithmetic limits (plus or minus) within which the actual error lies. The statistical error depends entirely on the amplitude of spatial changes in animal population density, that is, from place to place. If the animals are distributed relatively evenly throughout the territory, then the error will be small.

But if the animal population density has large differences in values (“where it’s dense and where it’s empty”), then the error is quite serious. It was on the analysis of statistical errors calculated based on the results of previous censuses that the “Standards for the volume of work and costs for conducting winter route census of game animals in the RSFSR” were compiled (Kuzyakin, Lomanov, Chelintsev; ed. Glavokhoty RSFSR, M., 1990).

The developers of these standards proceeded from the fact that the statistical error in counting large and well-accounted animal species by this method should not exceed 15 percent. The publication mentioned above contains a map showing areas with different recommended volumes of material for accounting over large areas.

Thus, in the central regions and in the north-west of the Black Earth Region, where differences in population density are large, mainly due to anthropogenic influences, it is necessary to lay 150 ZMU routes per one million hectares (and 35 trails). In most of the country, including most of the taiga zone, all of Eastern Siberia and the Far East, it is enough to lay out 30 routes and 7 trails per 1 million hectares. We repeat: for accounting over large territories, for conducting fairly reliable monitoring of resources, for determining production volumes in the constituent entities of the Federation.

In small areas, spatial changes in population density are almost the same as in large areas, usually less, but not much. Therefore, to obtain sufficiently reliable accounting results in each administrative district, each farm, it is necessary to lay out almost the same number of routes as in the entire region. And this makes accounting in small areas labor-intensive and very expensive.

From all of the above it follows that in principle there cannot be strict and constant standards for the volume of accounting material, especially for the entire country. Such standards, dictated by the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation (with surprising inconsistency in the volume of censuses), only indicate a lack of understanding by their developers of the fundamentals of scientific approaches in zoogeography, ecology and hunting resource science, in particular in the science of animal censuses.

Monitoring and accounting are not the same thing

Next - about counting and monitoring the state of hunting resources and populations of game animals. These two concepts are close, however, different. The census is aimed at determining the number of animals. Based on accounting data, the volumes of hunting removal of animals from nature can be calculated, which is the basis for the rational, non-exhaustive use of resources.

Monitoring is tracking the state of game animal populations in order to develop a policy for the economic exploitation of these populations. It is highly desirable to use credentials in monitoring, but it is not required. It can also use other data, for example, the epizootic state of populations, the current nature of seasonal movements of migrating animals, anthropogenic disturbances of the habitat, etc.

Many civilized countries conduct monitoring without any accounting and, in their policies for the use of game animal resources, rely on trends determined by other methods. In Russia, since the 30s, there has been a “Harvest Service” at VNIIOZ, which successfully uses a correspondent network and a questionnaire survey with mathematical processing of survey data.

The state hunting management body at the federal level is intended to monitor hunting resources and, on its basis, develop a general policy for the use of game animal resources. It is advisable to adjust this policy annually at the regional level, no lower.

What about taking into account? In the ugly law on hunting (No. 209-FZ) there are no concepts of accounting and monitoring at all. But in the basic law on wildlife there is a section that states that state registration, state monitoring and the state cadastre of wildlife are carried out by specially authorized state bodies at public expense.

The hunting department of the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation takes on functions unusual for it, descending to the scale of a hunting enterprise, not to mention financing enterprises for state registration. This contradicts not only common sense, but also the modern policy of the Russian President about the excess of state guardianship of economic entities.

We believe that accounting in small areas is a voluntary matter for business entities. To distribute quotas for the production of “licensed” species of animals, it is quite enough to obtain the total number for the subject of the Federation and distribute the total limit among regions and farms in proportion to the indicators of the registration of wild animals, which we have repeatedly written about in the hunting press and which is successfully practiced in a number of subjects of the Federation. And even more so, hunting in a region or farm cannot be prohibited on the basis of rejected registration cards.

Subject to the requirements of the latest methodological documents (project Nos. 1 and 58), any primary material can be rejected. This is what is done in many subjects of the Federation: for the slightest formal offense by the recorder of only one route (he did not put his last name on the record card, the total length of the route by land category does not correspond to the total length, etc.), government agencies reject the entire array of record material and close the hunt on a farm or in a subject.

What kind of atrocity is this?! State hunting management authorities should thank and bow to business entities that carry out at least 99% of the work on state registration of game animals, which, in principle, should be carried out by the state hunting system. It is illegal for government agencies to make drastic business decisions. This is “the misuse of the sacred task of animal registration,” which we have also written about several times. This, moreover, reveals a serious corruption component of all the rule-making activities of the Hunting Department in recent years.

Not only ZMU

ZMU is not the only method of recording game animals. In some documents, the Hunting Department of the Ministry of Natural Resources offers regions a choice of methods that are most suitable for local conditions. On the other hand, he “rested” only in ZMU, without developing methods and methodological documents for other accounting methods, stooping with his intervention in economic affairs down to “hunting grounds” of the order of several thousand hectares and making important economic decisions such as banning hunting.

At one time, a “Perspective program of accounting work of the State Service for Accounting of Hunting Resources of the RSFSR” was developed (Kuzyakin, 1982; ed. by Glavohoty of the RSFSR). In this program, Russia is divided into eight regions according to the set of methods used for recording game animals. For each region, from four to nine counting methods are proposed, while all species and groups of game animals are covered, and many major species can be counted by several counting methods. This is important because any accounting method not only has advantages, but also has disadvantages.

And only by joint analysis of the results of different counts can the shortcomings of each method be identified and the number of animals more accurately determined. It would be better if the Hunting Department began implementing this or a similar program, instead of ruining the entire accounting process in the country’s hunting sector. It would be better if he started creating a state cadastre of wildlife in terms of hunting resources.

After all, no one has yet repealed the law on wildlife! New methods of health care in 2012 and 2014. indeed they introduce overly strict and unnecessary requirements for performers and organizers of local accounting. We have already discussed the volumes of credentials above. But this is not the only absurdity. Appendix No. 1 to the order of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “Tsentrokhotkontrol” dated November 13, 2014 No. 58 states, for example, the need to lay out “equidistant and uniform” ZMU routes. The desirability of uniform placement of routes was discussed both in the Methodological Guidelines of 1980 and 1990, and in the Methodological Recommendations of 2009. However, the requirement of equidistant routes is completely impossible to fulfill, especially in mountainous conditions. Failure to comply with this requirement threatens the rejection of the primary data and, as a result, a ban on hunting.

It is also required that the length of routes be strictly proportional to the categories of hunting areas in relation to the area of these categories. This is completely unnecessary, since accounting data is processed separately by land category, and only then the numbers are summed up by land category. If poor fields or wetlands with few animals occupy large areas, then why waste effort and money on empty or almost empty routes? Stupid!

These Methodological Recommendations (pr. No. 58) prohibit passing the same route repeatedly. Why? The counting season is quite extended, and even after a week on the same route there will be a different situation with the number of tracks. This is a selective, “statistical” accounting!

We consider this requirement to be completely unnecessary. As well as the prohibition to conduct censuses after light powder on the same day.

At the same time, it is allowed to lay routes in mountainous conditions along the valleys of small rivers and streams. This contradicts previous methodological documents and principles of ZMU.

One can imagine that if animals cross a watercourse many times during their daily movements, then a route laid out, for example, along a hunting path along a stream, will “string” so many intersections of tracks that it can shift the census results towards overestimation several times over! And, conversely, when animals move along a stream, especially close to the shore, the counting route may not cross the trail or give a small number of crossings, underestimating the number several times.

In the theory of ZMU, there is such a concept: the average number of crossings per one daily trail of animals. In accounting, the bookmark of routes should be such that this number is observed, or it should be as close as possible to it. We believe that the record under discussion only shows the lack of professionalism of the compilers of the latest edition of the Methodological Recommendations and their lack of understanding of the theory of ZMU.

Where is the continuity?

Thus, what kind of continuity can we talk about if even in two frankly unprofessional orders drawn up under the leadership of A.E. Berseneva, is there a difference? There is no continuity in these orders from the Methodological Instructions of 1980 and 1990, which A.E. is constantly trying to convince. Bersenev. He is being disingenuous not only here. The top management of the Ministry of Natural Resources should be more careful in using digital data coming from the Hunting Department.

For example, in a letter to the Administration of the President of the Russian Federation V.V. To Putin, the Hunting Department gave unsubstantiated examples of a significant increase in game animal resources in recent years. Thus, the number of bighorn sheep has increased over three years by more than 47 percent, in an interview with the Minister of the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation to the Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper - only by 37%, although no one has taken into account the bighorn sheep for 20 years!

Returning to the problem of continuity, we can say that the methods of 2012 and 2014 will give results that are not comparable with the WMU data accumulated over a long series of years of the existence of the WMU (since 1962), which interrupts the necessary long-term monitoring of hunting resources.

What causes some bewilderment is the desire of the compilers of the latest methods to use constant conversion factors for each subject of the Federation to calculate the population density of animals. The average length of the daily course varies from year to year, sometimes quite significantly, depending on the depth of the snow cover, its density, and feeding conditions.

It varies depending on weather conditions throughout the recording season. The developers of previous methods focused on tracking the daily movements of animals evenly throughout the entire period of the route census, which created proportionality between the data of the two parts of the ZMU. The use of constant conversion factors is unacceptable!!!

At one time, we tried to calculate the so-called “forecast” coefficients, that is, to determine the appropriate coefficient based on the conditions of a particular winter. At least this was done for elk on the basis of actual tracking of daily movements in previous years (Kuzyakin, Lomanov. “Factors influencing the length of the daily movement of elk in the European part of the RSFSR.” Issues of accounting for game animals, tr. Central Scientific Research Laboratory of Glavohoty of the RSFSR; M. , 1986; pp. 5–21).

Unfortunately, the forecast coefficients did not work out: they turned out to be different in different areas with different trends in the dependence of the daily cycle on the depth of snow cover. In some areas, the stroke length changed little, but in others - quite strongly, by one and a half times or more. Consequently, the use of constant coefficients can distort accounting results by tens of percent and even 2 times.

This suggests that in the subjects of the Federation it is necessary to accumulate tracking material, try to establish the dependence of the length of the daily cycle on the conditions of the year, and in a particular year use the coefficients obtained in that year, even if only on a small tracking material. Do you need GPS?

We cannot agree with the mandatory use of GPS receivers in route accounting. In tracking the daily movements of animals, the use of satellite navigation is useful, at least to clarify the length of trails. Not as many census takers take part in tracking as in route recording, so fewer receivers-navigators are needed, which is very important when business entities have limited funds. Navigators don't help much on routes.

The length of routes can be measured using maps that are now available thanks to the Internet. Perhaps they would be useful for monitoring the execution of the route and the integrity of the accountants. But there are other ways for this purpose. For example, after finishing the accounting, the accountant calls the accounting manager by phone or radio and reports the place and time of the accounting, and the manager selectively checks the validity of the route.

This has been done for a long time in a number of subjects of the Federation. In addition, to process data on navigator tracks, special techniques, computer programs, their testing, production experiments and other aspects of preparing verified technology are needed. We consider the introduction of GPS technologies in the registration of game animals to be premature, especially with an urgent requirement and subsequent administrative conclusions.

The mathematical support for processing ZMU data in new methods remains the same (1980, 1990, 2009), however, without references to authorship. In the 2014 methodology, for completely unknown reasons, the formula for calculating the statistical error in bird counting disappeared.

SPECIALISTS OFFER

We, specialized experts on this issue, consider new methodological documents on ZMU completely unnecessary and even harmful, since they are compiled with many methodological errors, with ignorance of the theory of the ZMU method. They lead to a serious complication of accounting, a significant increase in labor and financial costs, to the possibility of corruption, violation of legislation and the emergence of social tension in the field of hunting, and ultimately to the final collapse of the accounting system in Russia.

Methodology for winter route census of mammals by tracks*

The essence of the method of winter route census of mammals

Winter route census is used to determine the number and population density of large and medium-sized (game) mammal species over large areas.

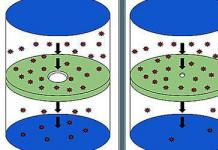

The count is based on counting the number of tracks of mammals of different species crossing a pre-selected and “worn out” route line. Naturally, the higher the population density of a particular animal in a given territory, the greater the number of tracks will be encountered during the route. However, there is another factor - the number of tracks left by an animal depends on its activity and the length of its daily cycle in these specific conditions. The longer the move, the greater the likelihood that the animal will cross the route strip.

Information about the length of the daily movement can be obtained in two ways: direct tracking with subsequent calculation of the average value and comparison of the number of tracks encountered with the actual number of animals, which is determined at trial sites using the multi-day sampling method. Such work is beyond the capabilities of not only schoolchildren, but also, in most cases, hunting farms. Therefore, it is carried out centrally - in different areas and for different conditions - and based on the data obtained, the so-called conversion factors are determined. To determine the population density of a given animal species, the counted number of its tracks crossing a route strip of known length is multiplied by such a conversion factor.

Conversion factors for 18 species of mammals, calculated based on materials from the State Hunting and Inspection Center of the Russian Federation, are given in Table. 1. Of course, they are approximate and may differ in each region of Russia in winters with different weather conditions, but they are quite suitable for educational and research work when conducting zoological and complex environmental expeditions with schoolchildren.

Table 1. Conversion factors for winter route census of animals (average data for 49 administrative regions of the Russian Federation for 1991–1994)

Where to keep records

Winter route censuses of animals can be carried out in most of Russia - with the exception of some southern regions that do not have stable snow cover in winter, tundras with very dense snow, and high mountains.

In hunting farms, when conducting censuses, all lands are conventionally divided into three categories - forest, swamp and field. Forest lands (“forest”) include all forests of various ages, including wetlands, as well as clearings, open spaces, clearings, clearings, burnt areas, and tracts of bushes. Wetlands (“swamp”) are considered only swamps that are open or overgrown with heavily oppressed (shorter than human height) trees. Open swamps may be surrounded by forest or fields - but even in this case they are classified as wetlands. Field land (“field”) includes all other open land: arable land, pastures, hayfields, meadows, tundra.

When conducting censuses for scientific research purposes, the division of the area into “lands” (habits) may be different, for example, more fractional - with the identification of several types of forests, depending on their age and species composition.

Census routes in the research area are planned based on the approximately proportional coverage of land available in the given territory. The simplest way to achieve such proportionality is to lay out a uniform network of routes, making sure that areas of land that are relatively poor in animals and birds are not excluded from the census. It is convenient to assign numbers to individual routes within such a network.

The length of each route, depending on local conditions, can vary between 5–15 km. The route can be either unidirectional or closed, based on the convenience of its passage. Moreover, it must be entirely rectilinear or consist of a small number of rectilinear segments. Open areas (including the central parts of large fields and swamps) must be crossed while maintaining the general direction. Routes should not pass along roads, wide clearings, along rivers and streams, forest edges, ridges, gullies and ravines. In addition, during the census you cannot: have a dog with you or use motor vehicles.

When to take counts

According to the standard methodology adopted in hunting farms, censuses should be carried out during the period from January 25 to March 10: at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of this period - in order to take into account changes in the average daily activity of animals.

Counts are not carried out during very severe frosts, prolonged thaws, during periods when crust or very dense snow appears, as well as on days with strong winds, snowfall or drifting snow. After heavy powder falls, counting is not carried out for 2–3 days.

If heavy snowfall or a blizzard begins during the route, work should be stopped and restarted after good weather has established.

How to carry out accounting

The winter route census of mammals is carried out over two days.

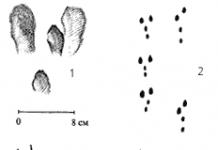

1 - paw prints of a white hare on slow jumps; 2 - location of brown hare tracks on slow (left) and fast (right) jumps; 3 - traces of a common squirrel in the snow

On the first day, the accountant, walking the planned route, erases all crossed tracks, so that the next day you can mark only those that appeared over the past day.

Grinding of traces occurs as follows: a wide spruce or pine branch is tied to the belt of a recorder moving on skis, which, trailing behind, covers up all traces. As a result, a “control-trail strip” 1–2 m wide is formed behind the recorder. (It must be assumed that dragging behind you for 15 km a branch that obliterates traces on a strip 2 m wide—in fact, a small tree—is beyond the power of one schoolchild. – Ed.)

Animal paths along the way should be covered with snow in order to determine the number of animals passing along them the next day. If on the day of grouting there were traces of large predators (wolf, wolverine, lynx), then the number of intersections of traces of each of these species is recorded in the notebook.

Traces of artiodactyls living in forests and tundra

1 - footprint of a female red deer; 2 - location of tracks of a female red deer; 3 - location of tracks of a male red deer; 4 - track of a male sika deer; 5 – elk trail

On the second day the accountant, passing strictly along the same route, notes in a notebook or on a route map all new tracks crossing the route,– indicating the type and number of animals that left traces, as well as the category of land. If an animal (wolf, fox, etc.), having approached the route trail, turns back, then this approach is still recorded as one crossing of the strip. When encountering tracks of animals that have passed along the same path (track after track), you need to follow it to the place where the animals dispersed and accurately determine their number. When encountering a large number of tracks (for example, fat marks) on a short section of the route, the total number of lane crossings is recorded.

1 - imprint of a wolf's front paw; 2 - prints of the front (left) and back (right) paws of a fox; 3 - location of fox tracks; 4 - imprint of the corsac's front paw; - dog paw print; - location of dog tracks.

The resulting number of marked animal crossings of the route strip follows correlate with general(within different categories of land) route length. The best way to measure its length is using large-scale topographic maps, forest plans, land management schemes, and hunting maps. The route is plotted on a map (or a copy thereof), and its length - for each category of land - is measured with a ruler, curvimeter or measuring compass.

If the route is laid along a forest block network, the length of the path can be measured block by block, knowing the distance between the clearings. It should be borne in mind that the sides of “kilometer” blocks in the central regions of Russia are imprecise and range from 0.8 to 1.2 km. Therefore, in all cases it is necessary to clarify the length of route segments using maps. The total length of the route and its extent in different areas are recorded rounded to the nearest 0.1 km.

Processing the results

Upon completion of each route, the accountant fills out a final card (Table 2). If the route did not pass through any category of land, “route length – 0 km” is indicated in the corresponding column. On the back of the card you can put a map of the route, with marked places where traces of large predators and ungulates were found (required in hunting). The diagram also marks the boundaries of forest areas, fields and swamps, rivers, streams, roads, clearings and numbers of forest blocks. Fill out the card with a ballpoint pen in legible handwriting.

Table 2. Winter route registration card for animals

It is convenient to summarize the results obtained in a special statement (Table 3). The first stage of calculations is the summation of the distances traveled during all surveys - separately for each category of land. The next stage is the summation of the number of intersections of a given type of animal traces noted during separate surveys of the registration strip, also separately for each category of land.

Table 3. Sheet for calculating the number of animals

Next, the total number of intersections of tracks in a given category of land is divided by the total length of routes (in km) and the result is multiplied by 10 km - thus calculating the standard indicator of the number of intersections per 10 km of route.

For example, in forest lands a route of 10.5 km was covered twice and 15.2 km once. In the first case, 1 intersection was noted, in the second - 2 and in the third - 5. The total length of the route will be 36.2 km, the total number of intersections is 8, i.e. (8:36.2)x10 = 2.2 intersections per 10 km.

Next, the resulting value is multiplied by the conversion factor for a given animal species (Table 1). The dimension of the coefficient is such that the final value is expressed in the number of individuals per 1000 hectares (10 km 2) and reflects the approximate density of the species in the studied area. This value is the final result of the winter route survey.

* Presented by the Euro-Asian Association of Youth Environmental Associations “Ecosystem”. This publication was prepared by the editors of "Biology"

A careful reading of the “Methodological recommendations for determining the number of ungulates, fur-bearing animals and birds using the winter route census method”, approved by order of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “Tsentrokhotkontrol” dated November 13, 2014 No. 58 (hereinafter referred to as the Methodology) leaves no doubt that the main message of this Methodology expressed in attempts to determine the number of hunting resources in order to establish quotas in each individual hunting area are clearly far-fetched and redundant. That if all the requirements of the Methodology are fulfilled, contrary to the authors’ claims that this Methodology allows reducing the costs of conducting winter route surveys, it repeatedly increases the labor and, accordingly, financial costs of hunting users. In addition, this Methodology contains a number of provisions that, in principle, cannot be implemented in full accordance with the requirements of paragraph 4.3 of the Methodology. The vaguely defined and overly stringent requirements set out in paragraph 4.3 allow the regulatory authorities to reject almost any survey route, while the rejection of at least one of the survey routes planned in accordance with the Methodology makes all the work of the hunting user pointless in conducting winter route surveys and all the labor and financial costs of the hunting user will be in vain. The new Methodology does not maintain the continuity of the approach when conducting winter route surveys.

- On determining the number of hunting resources in a separate hunting area in order to substantiate materials for an application for establishing production quotas.

Initially, the Winter Route Accounting Methodology (1990) was based on the following principles:

Winter route census is used to determine population density and numbers of game animals and birds in large areas.

The method of counting animals in the WMU is based on the fact that the average number of crossings of tracks of animals of the species being counted along a counting route is directly proportional to the population density of this species.

In turn, the number of crossed (counted) tracks depends on the average length of animal tracks. The longer the traces, the greater the likelihood of them crossing the accounting route.

Thus, to determine the population density of animals (the number of individuals per unit area), it is necessary to determine two indicators: 1) the average number of intersections of daily trails of the considered animal species per unit length of the route; 2) a coefficient associated with the length of the daily movement of animals.

Winter route surveys are not carried out in areas that do not have stable snow cover in winter, as well as tundras with very dense snow and high mountains.

Winter route surveys are not carried out during periods of very severe frosts, during prolonged thaws, during periods when crust or very dense snow appears, as well as on days with strong winds, snowfall or drifting snow. Thus, records are not taken on days with “extreme” weather conditions. After heavy powder falls, counting is not carried out for 2-3 days.

Winter route surveys should be carried out throughout the entire period from January 25 to March 10: at the beginning, in the middle and at the end. This is necessary so that the average tracking data corresponds to the daily activity of animals during the recording period.

Similar principles are set out in the 2009 Winter Route Recording Methodology, and here the most important thing is winter route accounting used to determine population density and numbers of game animals and birds over large areas

The new Methodology requires conducting a winter route census in each individual hunting area in order to determine the number of hunting resources to justify the materials for the application for establishing production quotas. This approach seems clearly redundant, erroneous and untenable. Every game warden working “on the ground” knows that the spatial distribution of game animals in the late winter period, when the census is carried out (January-March), cannot coincide with the spatial distribution of these animals before the start of fishing and during fishing (September-December). Too many natural, climatic and other factors influence the spatial distribution of game animals. During the counting period, the same elk is in stations with available winter food, and in the fall it uses other food stations. If we proceed from the principles of the new Methodology, then in a hunting area where there are winter moose stations, the removal quota will be overestimated, and in a hunting area where elk live in the autumn, it will be underestimated. What conclusion will any practical hunting expert, in whose lands there are no or few winter moose stations, draw from this? It’s absolutely correct to “draw” the crossings of the elk during the count, otherwise his farm will not receive quotas. The number of intersections shown by the performer, no matter how industry leaders would like it, cannot be controlled by anything or anyone. Determining the number in each hunting area, in order to justify the materials for an application for establishing quotas, should not be an end in itself; it is much more important to determine the number over a large area in order to monitor population dynamics compared to previous years and, on the basis of this, increase or decrease production quotas.

The Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia and Tsentrokhotkontrol, with their letters dated December 4, 2014 No. 15-29/27832 and dated December 9, 2014 No. 590, add even more confusion to the situation with the winter route accounting method and actually disavow the need to introduce a new Methodology. The letter from Tsentrokhotkontrol states that “In accordance with clause 11 of the Procedure for maintaining state records, the state cadastre and state monitoring of fauna objects by order of the Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia dated December 22, 2012 No. 963, measures to record the number and distribution of fauna objects are carried out in in accordance with accepted methods, and in their absence - according to existing scientific approaches to accounting for species or groups of species of objects of the animal world. Thus, when conducting a census of the number of hunting resources using the winter route census method, game users can also be guided by Order No. 1 or other available accepted methods and scientific approaches.”

In a letter from the Russian Ministry of Natural Resources, this is explained in more detail: “The counting of the number of hunting resources can be carried out in accordance with the Methodological Instructions for the organization, conduct and processing of data on the winter route count of game animals in the RSFSR, approved by the Deputy Head of the Main Directorate of Hunting of the RSFSR V.I. Fertikov on June 20, 1990 g., and Methodological recommendations for organizing, conducting and processing data from winter route registration of game animals in Russia, recommended for publication by the Ministry of Agriculture of Russia on May 28, 2009, protocol No. 15.”

The main principle of these Methods is accounting over large territories and the organizers of accounting are the state executive bodies of the constituent entities of the Russian Federation. If hunting users make in their lands the previously planned number of counting routes and daily “tracking”, then without a unified approach and without coordination of these counts on the part of government bodies, this will be a waste of time, but formally the hunting user will fulfill his responsibilities for recording hunting resources.

In addition, the post-harvest abundance of hunting resources cannot be the only key point in setting production quotas. In this case, much more important, in addition to the post-harvest number, is a factor that in recent years we have completely forgotten and do not use at all, namely: the actual population growth and the actual pre-harvest population size. In my practice, there have been seasons when, despite a good post-harvest population of the main commercial species - sable, the next fishing season turned out to be a failure, the actual production barely reached a third of the production quota and the bulk of the commercial harvest was made up of adult individuals, that is, there was virtually no increase in these seasons.

2 . About labor and financial costs when conducting accounting according to the new Methodology and how feasible some of the requirements of this Methodology are.

Let’s try, using the example of one of the hunting farms that are members of the NP “Association of Kamchatka Game Users” (NP “AKO”), to show how much labor and, consequently, financial costs increase when conducting winter route accounting according to the new Methodology and how feasible the requirements of paragraph 4.3 of this Methodology are.

The territory of the farm is located in one administrative district and consists of three hunting grounds. The total area of the farm's territory is 373.8 thousand hectares (hunting ground No. 1 - 272.8 thousand hectares, hunting ground No. 2 - 41.6 thousand hectares, hunting ground No. 3 - 59.4 thousand hectares), which is just over 5 % of the total area of the district. The relief of all hunting grounds has a pronounced mountainous character. Movement is possible only along slopes along streams and small rivers and along the valleys of larger rivers.

In 2013, the farm carried out winter route surveys together with neighboring farms, members of the NP "AKO", combining their hunting grounds into a single study area. In total, 15 routes were laid out on the farm, with a total length of 163.9 kilometers, all routes were completed after grouting, thus, the total length of the accounting routes was 327.8 kilometers.

In 2014, the farm carried out censuses in the study area, which included hunting grounds of the entire administrative district. The farm had 10 routes with a length of 50.8 kilometers. The total length of the routes, including grouting, was 101.6 kilometers.

According to the new Methodology, in 2015, the farm must conduct winter route surveys in each hunting area. In accordance with paragraph 4.2 of the Methodology, in hunting ground No. 1 you need to walk at least 287.3 km, in hunting ground No. 2 - 143.2 km, in hunting ground No. 3 - 167.5 km or a total of at least 598 km, and taking into account that grouting is a mandatory requirement of the new Methodology - at least 1196 km or 11.7 times more than in 2014. Labor intensity increases more than tenfold. Apparently, all hunting users in the Kamchatka Territory will experience the same increase in costs. Are these costs really necessary? And by what forces and with what funds will censuses be carried out on publicly accessible hunting grounds or will production quotas be established in them without determining the number? If so, then there is a selective approach to establishing production quotas depending on the status of hunting grounds.

And that is not all.

In accordance with paragraph 4.3 of the Methodology, the length of all survey routes in the study area for each group of habitat categories of hunting resources must be proportional to their areas. Based on this, in hunting ground No. 1, the length of survey routes in the “forest” category should be 204.8 km, in the “field” category, which includes tundra and char - 81.3 km, in the “swamp” category - 1, 2 km. In order not to overload the material, we will not provide calculations on the length of survey routes and their planning for the two remaining hunting grounds. In accordance with the Methodology, the length of each route should be at least 5.0 km and no more than 15.0 km; let’s imagine that on average each survey route will be 10.0 km, then it is necessary to place 28-29 survey routes in the study area. Repeated passage of survey routes using the new Methodology is prohibited. In accordance with the requirements of the Methodology, survey routes must be located evenly and equidistant from each other across all groups of habitat categories in the study area. This requirement “on the ground” cannot be fulfilled in principle, no matter how much the performers would like it, it is still not possible to place survey routes “evenly and equidistantly” on the ground, somewhere the survey routes will be closer to each other, somewhere further away. And this is a reason, in accordance with paragraph 18.1 of the Methodology, for culling accounting routes.

If at least one route is rejected for this or any other reason, then the total length of the accounting routes will correspondingly decrease and the requirements of paragraph 4.2 of the Methodology for the minimum length of accounting routes will be violated and all accounting materials will be rejected.

Habitat categories are also not evenly distributed throughout the study area. On the map, you can plan the length of survey routes in strict accordance with the proportionality of the areas of habitat categories, but it is very likely that on the ground everything will turn out to be completely different, and the length of the survey route on “paper”, due to the “ravines,” may not coincide with the length of the actual survey route traveled. With such a volume of field work on a farm, censuses can only be carried out by several census takers, and only after processing the survey routes they actually traveled can it be determined whether the proportionality of the length of survey routes for each habitat group is observed to the areas of these categories in the study area. What if it is not complied with? All accounting must be rejected. The Methodology does not allow deviations from proportionality of even a tenth of a percent or proportionally or all work is thrown into the trash.

All these requirements, among other things, carry elements of “corruption”; one user can accept the work “closing” his eyes to the lack of uniformity and equidistance or lack of proportionality, and reject another user - stating that the same is not maintained between accounting routes everywhere distance and they are not equidistant.

3. On the continuity of the new Methodology for winter route accounting For two years, winter route census was carried out according to the “Methodological guidelines for the implementation by executive authorities of the constituent entities of the Russian Federation of the delegated powers of the Russian Federation to carry out state monitoring of hunting resources and their habitat using the winter route census method” approved by order of the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation dated January 11, 2012 No. 1 .

For two years, data on the number of hunting resources obtained as a result of censuses using these Methodological Instructions were used to substantiate materials for the application for establishing production quotas. And suddenly it turned out that “data obtained from hunting lands combined into one study area can only be used for the purposes of monitoring the dynamics of the number of hunting resources, but not for the purpose of setting quotas for the production of hunting resources in individual hunting lands.” (Letter from the Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia dated December 4, 2014 No. 15-29/27832) It turns out that for two years all the constituent entities of the Russian Federation illegally set production limits and quotas? And the federal executive body, in violation of the requirements of its own order, agreed on these production limits and quotas. No - the legislation was not violated, this is just a clumsy attempt to explain the need for a new Methodology, since paragraph 3 of the Methodological Instructions states “Data from the census of animals and birds using the winter route census method is used to determine quotas for the production of relevant types of hunting resources...”. Why, then, did there arise a need to change the Winter Route Accounting Methodology and, as a justification, flog ourselves by accusing ourselves of illegally agreeing on production quotas?

When introducing the previous Methodology for winter route accounting, we were convinced that in order to obtain reliable results, it was extremely important that at least 35 accounting routes with a length of at least 350 km were laid out in the study area; now it turned out that this was an excessive requirement, according to the new Methodology for To obtain reliable results, 7 survey routes with a length of at least 50 km are sufficient and, according to the authors, this does not in any way affect the reliability of the results.

All previously existing Methodologies for winter route census excluded the conduct of survey routes in the tundra zone and highlands; the new Methodology requires the inclusion of tundra, desert and stones in the “field” habitat category and requires the mandatory construction of survey routes in these categories, which, of course, violates the continuity and the results obtained using this Methodology cannot be compared with the results of previous accountings.

The previous and new Methods abandoned one of the main principles of winter route counting - the number of intersections depends on the average length of the animal's tracks (daily course), the longer the track (daily course), the greater the likelihood of its crossing by the counting route. Refusal to determine the daily cycle when conducting winter route censuses and the establishment of constant conversion factors, regardless of natural and climatic conditions during the census period, has a much greater impact on the results of determining the number of hunting resources and casts doubt on the reliability of these results. Moreover, the conversion factors were determined based on the results of “tracking” the daily course in the era of the absence of instrumental control, when the length of the daily course was determined mainly “by eye” and it is precisely this indicator of winter route accounting that requires verification by instrumental methods.

Conclusions:

- There is no objective need to determine the number of hunting resources in each hunting area, and therefore to introduce a new Methodology for winter route accounting.

- The methodology has one single goal - to provide instrumental control over the conscientiousness of field work carried out by accountants.

- The technique repeatedly increases the costs of hunting users for carrying out registration work.

- A number of requirements of the Methodology cannot be fulfilled by hunting users in principle.

- The methodology contains elements of corruption.

- Hunting users can, and therefore should, conduct winter route surveys in 2015 using the 1990 or 2009 Methodologies.

Winter route census (WRC) is the most common method of wolf census in the forest zone. ZMU is a comprehensive relative accounting of game animals

According to the “Methodological guidelines for organizing, conducting and processing data from winter route census of game animals in the RSFSR,” the survey of game animals is carried out from January 25 to March 10. The route is laid out based on approximately proportional coverage of land categories. It can be either unidirectional or closed, based on the convenience of its passage. The length of the route, depending on local conditions, can be within 5-15 km. All work is carried out in two days. On the first day (the day of grouting), while walking along the route, the accountant erases all traces so that when passing the route the next day, he can mark only fresh, newly appeared traces. Wolf tracks are also taken into account on the first day to establish the presence of the animal, although this data is not processed. On the second day (the day of counting tracks), walking along the route, the recorder marks all new tracks, and if the wolf, having approached the ski track, turned back, then this approach is recorded as crossing the route. When encountering tracks of animals that have passed along the same path (track after track), you need to walk along the trail to the place where the animals separated and accurately determine their number. When keeping records, a card for winter route registration of game animals is filled out.

During the count, you cannot: shoot animals, have a dog with you, or use motor vehicles and well-worn roads.

As a result of accounting according to the formula A.N. Formozov (1932) with a correction factor (proportionality coefficient equal to 1.57) by V.I. Malyshev and S.D. Pereleshin, the number of animals is calculated. When constructing the formula, the author proceeded from the fact that the more traces of animals are found along the routes in winter, the higher the population density of the species should be. Currently, with an amendment found in various ways and independently of each other, the formula for the route accounting of animals by tracks looks like this:

P—animal population density, number of individuals per 1 km2;

S -- number of trace intersections;

m -- route length, km;

d -- the average length of the daily movement (travel) of animals, km.

The calculation of the number of wolves is not much different from that for other species, but it should be borne in mind that the average length of a wolf’s daily walk, accepted by S.G. Priklonsky and E.N. Thermal (1965 - Quoted from Grakov, 2003) for 20 km, may be noticeably higher.

According to Teplov (1995), winter survey routes should be constant, then the survey results can be compared from year to year. This method is quite simple and accurate. But the unscrupulous attitude of hunting workers towards animal counts and, as a consequence, the erroneous data obtained, discredit this method of accounting. Another disadvantage of the method is the impossibility of its use in the southern regions that do not have stable snow cover in winter, as well as in the tundra zone with very dense snow cover. The dependence of the census on weather conditions is also a negative characteristic of this method. But, despite all these shortcomings, the method has become widely used in our country.

The history of absolute methods for counting animals on trail routes begins with the work of A. N. Formozov (1932), in which he first published a formula for quantitative counting.

When constructing the formula, the author proceeded from the fact that the more traces of animals are found on routes in winter, the higher the population density of the species should be; The greater the distance an animal runs per day, the lower the population density of the species should be, given equal occurrence of tracks. Thus, the population density z is directly proportional to the number of tracks S and inversely proportional to the length of the route t and the length of the daily track of the animal d:Z = S:md.

A. N. Formozov, based on proportionality, nevertheless put an equal sign between the left and right sides of the formula. Experts soon noticed that this formula is a proportion, requiring a proportionality coefficient to bring it into equality. This coefficient was found in different ways and independently of each other by V. I. Malyshev (1936) and S. D. Pereleshin (1950); it is equal to π/2 (or with some rounding 1.57) and is called the Malyshev-Pereleshin correction. Subsequently, several other researchers came to the same constant correction of 1.57 in different ways.

What does this correction mean, i.e. a constant coefficient of 1.57?

Let us assume that we have only linear daily traces. At the end of every inheritance we have a beast. If all the tracks are stretched in one direction and if the route runs strictly perpendicular to the lines of the tracks, then the population density of animals can be calculated using Formozov’s formula without any corrections: the number of animals equal to the number of crossed tracks would relate to a counting strip with a length equal to the length of the route and a width of the length of the animal's daily movement.

Now let’s complicate the task: we will place the straight lines at different angles to the route line. The likelihood of crossing the heritage route has decreased. For those tracks that remained perpendicular to the route (90° angle), the probability of their intersection remained the same. For tracks that are elongated along the route (angle 0°), the probability of intersection is zero: theoretically it is impossible to cross them, since parallel lines never intersect.

How many times has the average probability of crossing trails decreased with the entire set of diversely placed trails, or how many times has the width of the registration strip decreased compared to the perpendicular arrangement of routes? Apparently, the probability of crossing the trail can be expressed by the length of the projection of the trail onto the perpendicular to the route. With perpendicular tracks, the probability is maximum and can be expressed in terms of 1; with tracks parallel to the route, the probability is zero; with an intersection angle of 30°, the projection of the segment is equal to half of it and the relative probability of intersection can be expressed as 0.5, i.e., it is proportional to the sine of the intersection angle. For all possible angles of intersection of the daily trail and the accounting route, the probability of intersection will be expressed by the arithmetic mean of the sines of various angles. This figure is 0.6366. Compared to one (probability for perpendicular tracks), the probability of intersection of tracks located at angles to the route decreased by 1: 0.6366 = 1.57 times; the width of the registration strip, which includes animals whose tracks were crossed by the route, has decreased by the same amount.

Thus, Formozov’s formula without correction is suitable only for the case when all traces are straight and perpendicular to the route; with an amendment of 1.57 (in the numerator), the formula is suitable for various angles of intersection of tracks along the route.

Let's see what happens to the curved, bent legacies of various configurations during the daily movements of animals? Here the famous Buffon problem can be called upon to help, with the help of which the needle problem, one of the most significant problems in probability theory, was solved. Buffon showed that the mathematical expectation of the number of intersections of a needle repeatedly and randomly thrown onto a surface with drawn lines is strictly proportional to the length of the needle, regardless of its shape. This means that the number of intersections must be constant, no matter how the needle is bent or straight.

For accounting purposes, the lines drawn on the surface can be taken as accounting routes, and the needles as the daily tracks of animals. This means, whatever the configuration of the daily tracks, the number of their intersections should not change if the number of tracks and, accordingly, the number of animals are the same. Buffon's problem also means that Formozov's formula with an amendment of 1.57 is suitable not only for rectilinear traces, but also for traces of any configuration, if the numerator of the formula contains the number of intersections of traces, if all intersections of all individuals are counted, regardless of how many times every animal crossed the route line.

Logically, Buffon's problem can be explained as follows. Let's make segments of soft wire and imagine that these are the daily remains of animals. If you throw wires on a piece of paper

with drawn lines and write down the number of throws and intersections, then their ratio should not change when the shape of the wires changes. When they are straight, they will more often fall on the lines - routes, but always give one intersection. When bending the wires, the daily tracks will become more compact, and the more complex the configuration of the track, the more compact it will be. Because of this, they will lie on the route lines less and less often. But if the legacy falls on the route, it will immediately give many intersections.

Thus, the number of successful wire throws onto the route line is closely related to the number of intersections of the trail and the route. This relationship is inversely proportional. For this reason, the probability of getting, say, 100 intersections of a trace with a route does not depend on the wire configuration: with the same density of routes and the same length of wires, it is necessary to make approximately the same number of throws for different configurations of traces.

In Buffon's problem there is a condition that the lines on the surface (counting routes) are drawn in parallel at the same distance from each other. The magnitude of this distance does not affect the main conclusion; it only matters for the number of throws, as a result of which a certain number of intersections must be obtained. So, if the distance between parallel lines is equal to the length of the wires, then with a large number of throws and ensuring complete randomness of the experiment, the number of intersections will be approximately 1.57 times less than the number of throws. The sparser the lines are, the more throws are needed to obtain a given number of intersections, and, conversely, the denser the lines are, the fewer throws are required.

It is possible to prove the validity of the Formozov formula with an amendment not only for rectilinear, but also for any curvilinear traces not only using the Buffon problem, but also using reasoning used in differential calculus. Each curved line can be represented as a set of extremely small straight segments for which all conclusions concerning the whole direct inheritance are valid. In a popular form, such reasoning was carried out by V. S. Smirnov (1969), and S. D. Pereleshin (1950) used one of the differential calculus formulas to determine the coefficient 1.57. Formozov (1932) spoke about the need to assume the straightness of all traces. In this case, it does not matter which of the two indicators is in the numerator of the formula: the number of intersections of tracks or the number of individuals whose tracks are crossed by the counting route, since with straight tracks the track of each individual will give only one intersection and the number of crossed tracks and intersections of tracks will be equal . Apparently, for this reason, A.N. Formozov did not specify which indicator should be substituted into the formula.

However, with curved daily heredity of animals, the indicator put in the numerator is of great importance. The more tortuous the track, the more intersections of tracks will be given by one track (the daily course of one individual) and the greater will be the difference between the two indicators under consideration. Above we talked about the universal validity of the formula with an amendment of 1.57 if the numerator is the number of intersections of tracks, and not the number of individuals whose daily tracks are crossed by the route. What happens with the formula if you substitute the number of individuals (inherits) into the numerator?

O.K. Gusev (1965) proved that if the numerator of the formula contains the number of individuals, then its denominator must include the average diameter of the individual’s daily area, i.e., the space enclosed in the daily footprint of one individual.

Logically this can be explained as follows. Let us assume that the denominator of the formula denotes the area of the counting tape, the length of which is equal to the length of the route, and the width is the distance within which the individual can be located. The animal is at the end of its daily course, and the maximum possible distance from the route to the animal is equal to the diameter of its daily trail (daily hunting area). With this maximum distance, the animal may be close to the route, but not be included in the count if the route did not affect its daily movement. Weighing all possible options, we will come to the conclusion that the average width of the counting tape in one direction from the route is equal to half the average diameter of the daily area, and the width of the entire tape is equal to the whole average diameter (diameter) of the animal’s daily area.

In other words, the value of the average diameter of a daily area means the probability of the trail crossing the route, the probability of detecting an individual. The smaller the diameter, the lower this probability, therefore, when counting, it is necessary to take a smaller width of the abstract count strip according to the average diameter of plots of a given type in a given place and time of counting.

When using the number of encountered individuals (legacies) in the numerator, and the average diameter of the daily area in the denominator, no correction to the formula is necessary.

Thus, A. N. Formozov’s formula was refined and transformed in two directions - using in the numerator the number of intersections of all tracks and the number of individuals whose tracks are crossed by the route.

The first in-depth critical analysis of the possibility of using these indicators was carried out by O.K. Gusev (1965, 1966), but the author did not fully differentiate between these indicators, leaving behind both of them the same letter symbol S. It seems that these different indicators need assign different symbols: after the number of intersections of tracks leave the letter S (the initial letter of the word “trace”, according to the author of the formula), and after the number of inheritances (individuals, daily movements of animals) - the letter N (the initial letter of the word “inheritance”). Since currently the number of individuals per unit area of land is most often called population density, it is advisable to replace the symbol z (the initial letter of the word “stock”) with the symbol P (the initial letter of the word “density”). The remaining symbols correspond to the meaning of the designations: m - route, d - trail length, D - diameter, the average diameter of the animals' daily range.

So, by now we have two formulas for route recording of animals based on tracks in the snow:

P = 1.57S:md, P = N:md,

where P is the population density of animals, the number of individuals per 1 km 2;

S - number of intersections of tracks;

N is the number of daily tracks (individuals) crossed by the route;

m - route length, km;

d is the average length of the daily movement (legacy) of animals, km;

D is the average diameter of the animal’s daily range, km.

If you substitute not kilometers in the length of the route, but the number of tens of kilometers (for example, if 250 km are covered, 25 tens of kilometers are substituted into the formula), then you can determine the number of animals per 1000 hectares of land.

There is another formula that is used to calculate data on the winter route census organized by the biological survey group of the Oka Nature Reserve:

where P is the population density of animals;

P y - accounting indicator: the number of intersections of tracks per 10 km of route;

K is a constant conversion factor.

This formula is suitable for any combined accounting, where route accounting of traces is used as one of the methods. The K coefficient is determined by some other method. I.V. Zharkov and V.P. Teplov (1958) propose on-site accounting for this; the coefficient is necessary to move from a relative accounting indicator to an absolute accounting indicator.

S.G. Priklonsky (1965, 1972) proposed determining the K coefficient based on tracking data along the length of the daily cycle.

The author carried out modeling of winter route surveys to determine the reliability and mathematical correctness of the formulas. An area measuring 320X500 mm was outlined on a sheet of paper, which on a scale of 1:50,000 depicted an area of 400 km 2. On this square, daily traces were drawn, taken from the materials of the tracking of 3 species of animals. Thus, the natural configuration of the tracks was maintained, which were brought to a scale of 1:50,000, and the tracks of the hare, hare and moose were equated approximately to the size of the sable's daily movements.

Each inheritance was previously drawn on a separate sheet of thick paper, where all the parameters of the inheritance were entered. From here its shape was copied onto a model area of 400 km 2. On the model scale, the length of the tracks varied from 3.5 to 14 km, with an average of 8.7 km; the average diameter of the animals' daily range ranged from 1.8 to 3.7 km.

First, individual routes were placed on the model area randomly (by throwing a ruler), then a network of routes equally spaced from each other. In both cases, the results were close, with straight and curved routes giving no difference in results. The network of routes drawn over 2 km at the model scale was first placed parallel to the frame of the rectangular model area, then rotated 15° 6 times, and each time the intersections of the routes of tracks were recorded. Thus, a network of routes crossed the area at various angles, spaced 15° from each other.

In each experiment, the length of a separate route was measured, the number and numbers of crossed tracks, and the number of intersections of tracks of each track were determined.

Thus, knowing the length of tracks and the diameters of the daily ranges of animals, the number of intersections of tracks and tracks, the length of routes, we had all the data to determine the population density of animals on the site and thereby check the mathematical correctness of the formulas on a model that is as close as possible to the winter route census in field.

The actual population density on the model site was also known based on the number of heritage sites located on it. The difference between the experimental population density and the actual population density in the model was the error, and its ratio to the actual density was the relative error as a percentage. The errors were both positive (in the experiment the number was overestimated) and negative (the number was underestimated).

The resulting errors in calculating numbers using both formulas are not large. This means that the formulas are correct and can be used in animal accounting practice.

The models marked the number of each trail crossed by the route. During the modeling process, sufficient material was accumulated for each inheritance to determine the number n for it. In order to obtain more voluminous material and a more reliable indicator, each inheritance depicted on a separate card was subjected to processing. Transparent tracing paper with parallel lines every 2 mm was randomly applied to the image of the footprint, and the number of intersections of the traces was determined along each line (route). Then the tracing paper was rotated 15° relative to the first position and again the number of intersections was determined for each route. The tracing paper was rotated at an angle of 15° until it returned to its original position. In this way, we obtained sample data on all possible directions of intersection of the trail by a route and all routes located at different distances from the edges or middle of the trail. This ensured randomness and truly determined the average value of n. During this experiment, an average of 815 intersections of traces 5 and 357 intersections of traces N were obtained for each of the 32 traces. The obtained data were substituted into formula 5, and it turned out that the length of the traces was very close to the value of 1.57 nD. This applies not only to data averaged for inheritances of various configurations, but also for each specific inheritance.

Comparing the errors obtained with three methods of processing the material, we can say that the smallest errors were according to the formula with the average diameter of the daily trace. Here the biggest error was a little more than 7% when the route crossed only 28 animal heirs.

When the length of the marks was measured with a curvimeter, the errors were maximum: here, to all other errors, the inaccuracy of measuring the length of the mark with a curvimeter was added. Judging by the predominance of positive errors, there was some underestimation of the length of the inheritances. In fact, the scale division of the curvimeter is 1 cm, while the diameters of the daily range of animals were measured with a ruler with millimeter divisions. In addition, in a curvimeter, deviations from the true length are more likely due to backlash in the mechanism parts. There is no doubt that straight lines are easier and more accurate to measure than curved lines. This applies not only to the model, but also to the field conditions of the census.

The errors obtained when calculating the length of the trace from its diameter turned out to be somewhat smaller than when measuring the traces with a curvimeter. However, they were larger than when processing materials according to the formula with a trace diameter. The difference was only in the numerator of the calculation formulas: in one case there was the number S, in the other - N. It would seem that according to the formula with S, the number of accounting units is greater, so statistical errors should be smaller. In the model it was the other way around.

This is explained by the fact that the exponent 5 is a much more random value than N. The number of intersections S contains the value n, and if n is obtained on the routes, which is not equal to the average for a given inheritance configuration, an error occurs. A careful analysis of the placement of traces on the models showed that maximum errors occur when a certain orientation of the traces involved in calculating the reliability of the methods predominates. Despite the fact that in each experiment data was calculated along a network of mutually perpendicular routes, errors occurred, and the errors were considerable.

All this concerns the ideal conditions of the model, when a certain orientation of the inheritances was obtained by chance. In the field, the regular orientation of the daily movements of animals is a frequent phenomenon, and it manifests itself much more strongly than in the model. In this regard, during field surveys, special attention should be paid to a very important methodological detail: routes should be laid in different directions relative to the terrain, in particular relative to linear elements of the terrain.

Routes that run perpendicularly and at an angle to roads, river and stream valleys, forest edges, other natural boundaries, etc. not only more proportionately cover the areas of different types of land, but also cross the tracks of animals at different angles, which ensures correct averaging of the number intersections. After all, the daily movements of animals are often extended along oxbow lakes, streams, hollows, ridges, edges, boundaries of forests and woodlands, and other relief elements, and often, on the contrary, extend across these linear elements. During migrations, the heritages are also extended in one specific direction. Animals often run along the edge in both directions, leaving several threads of tracks stretched along the edge, and sometimes in one zigzag, as if stitching together two bordering phytocenoses. In the first case, the trail will give the maximum number of intersections if it is crossed across the edge, in the second - along the edge. In both cases, the resulting number of intersections will be far from the average, which will lead to significant accounting errors.

Thus, in order to obtain a truly average number of intersections per track, it is necessary to lay routes in different directions, at different angles to the linear elements of the terrain.

Accounts on routes, carried out according to two different formulas, are carried out differently. For the formula, with the length of the daily movement of the animal, the intersections of tracks are recorded in the field, regardless of the number of individuals that left these tracks. When counting using another formula, with the average diameter of a daily area, it is necessary to count the number of individuals that left tracks crossed by the route, and for this it is necessary to determine whether the individual left the same track as the previous one crossed, or a different one. This determination is called trace identification.

Only an experienced hunter-counter can identify traces during a census. Therefore, accounting using a formula can hardly be entrusted to a wide range of accountants who have different, including low, qualifications in accounting. For this reason, in large areas, a formula is used that requires only one day to erase all old tracks, and the next day to count all intersections of new tracks of each species. Any accountant can do this work.

For accountants who have extensive experience, it is advisable to carry out accounting using two formulas at once. In this case, not only the number of intersections of tracks is noted in field records, but their identification is also carried out (the number of individuals is determined). Based on tracking data, it is possible to immediately determine two values - the length of the daily course and the diameter of the daily area - and simultaneously carry out two mutually controlling calculations of the population density of animals. When identifying traces, qualified accountants can be guided by the recommendations of G. D. Dulkeit (1957) and O. K. Gusev (1966). O.K. Gusev (1966) suggests using seven identification signs simultaneously:

1. Freshness of the trail. Even within a day, the tracks of animals undergo changes: the snow becomes compacted, or the tracks are dusted with snow, covered with frost, or spread out during the thaw. The author suggests using artificial traces left by the census taker using a stick or plank during the night at intervals of 2 hours; in the morning they will harden to varying degrees, and a morning inspection and turning over the track will later help to accurately determine the freshness of the track on the route.

2. Direction of the trail. Marked on the route outline. This sign is very important and often allows you to accurately recognize the tracks of two animals.

3. Visual assessment of the trail. Each crossed track is carefully examined, the recorder tries to capture in memory the size and nature of the paw prints of the animals. Measurements on loose snow are not accurate and can be misleading. Experienced hunters always believe that there is no need to measure the trail, you need to look at it.

4. Taking into account the probability of encountering traces of the same animal at a certain distance. The track of the same animal is unlikely to be encountered again on a route through a distance exceeding the maximum diameter of the animal's daily range or the length of its daily course.