Svobodnensky steamships - river minesweepers KAF

According to archival data (added, corrected) by V.G. Parshina

As is known, a number of Svobodnaya tugboats were temporarily mobilized into the KAF (Red Banner Amur Flotilla) before 1945, during the Great Patriotic War and the Soviet-Japanese War, and here they were converted into river minesweepers (RTSh).

Among such Svobodnensky (in the 1940-1970s) steamships were: “Kharkov”, “Chkalov”, “Zhuravlev” and “Chernenko”.

One Svobodnensky steamship was converted into a gunboat: “KL-32” - “Grodekovo”.

Below is brief information about these steamships - river minesweepers.

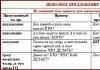

Brief general information:

Type "Leningrad". Displacement 293 tons. Dimensions 48.5 x 13.4 (wheel casings) x 1.5 m. Boiler-machine power plant, 300 hp. Speed 16.7/7.5 knots, range 950 miles. Armament: 1 x 45 mm, 2 x 4 x 7.62 mm machine guns, 50 mines of type "P" or 10 mines mod. 1908, lightweight Schultz and boat trawls. Crew 47 people.

RTSH-3 - steamer "KHARKOV"

(until September 25, 1940 and from November 6, 1943 “Kharkov”)

River wheeled tugboat.

Built in 1932 - 1934. ("Lenin's Forge", Kyiv).

Called up on March 5, 1935, converted into a minesweeper and included in the Amur Flotilla. Passed the cap. renovation in 1940

Disarmed on November 6, 1943 and converted into a tugboat.

RTSH-52 - steamship "CHKALOV"

(until 07/13/1941 and from 10/22/1945 "Chkalov")

RTSH-56 - steamer "ZHURAVLEV"

(until 08/15/1920 "Al. Bubnov", until 09/15/1922 "Pavel Zhuravlev", until 05/4/1923 "A. Bubnov", until 07/25/1929 "Pavel Zhuravlev", until December 1929 TZ-1, until 05/05/1932 "Pavel Zhuravlev", until 07/13/1941 and from 10/24/1945 "Zhuravlev")

Built in 1902

On August 15, 1920, she was included in the Amur Flotilla as an armed steamship. 09/15/1922 disarmed and transferred to Blagoveshchensk Rupvod. Called up on July 25, 1929, armed and included in the Far Eastern Flotilla as a minesweeper. In October - November 1929, he took part in hostilities (conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway), after which he was disarmed and returned to the NKPS. In the period from 05/05/1932 to 05/24/1934. was part of the Amur flotilla. Mobilized on July 13, 1941, converted into a minesweeper and included in the Amur Flotilla. Participated in the Manchurian offensive in August 1945.

RTSH-57 – steamship “CHERNENKO”

(until 05/04/1923 "To Kovalevsky", until 07/25/1929 "G. Chernenko", until December 1929 TZ-2, until 07/13/1941 and from 10/24/1945 "G. Chernenko" ")

River wheeled tugboat.

Built in 1907

Called up on July 25, 1929, armed and included in the Far Eastern Flotilla as a minesweeper. In October - November 1929, he took part in hostilities (conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway), after which he was disarmed and returned to the NKPS. In the period from 05/05/1932 to 05/24/1934. was part of the Amur flotilla. Mobilized on July 13, 1941, converted into a minesweeper and included in the Amur Flotilla. Participated in the Manchurian offensive in August 1945.

Disarmed on October 24, 1945 and converted into a tugboat.

Gunboat

KL- No. 32 – steamer “GRODEKOVO”

(until 07/28/1941 and from 10/13/1945 "Grodekovo", from 02/10/1944 "KL-32")

Laid down in 1936 ("Krasnoe Sormovo", Gorky), launched in June 1937, erection. commissioned in the fall of 1937

Mobilized on 07/22/1941 and on 07/28/1941 became part of the Amur Flotilla. Participated in the Manchurian offensive operation 9.08 - 1.09.1945.

10/13/1945 disarmed and returned to the river shipping company.

Decommissioned on December 23, 1968 and scrapped.

There is a man in Khabarovsk who not only saw paddle steamers on the Amur in his lifetime, but also managed them. Georgy Tomovich Lapodush still does not forget his “Ilyich” - an old two-pipe and two-deck ship, the captain’s bridge of which he entered back in 1958. It was this very same ship that, half a century later, the writer Georgy Lapodush would include in the love-tragic story “Earthly Destiny.” His heroine Mia Vyashchina rode it. The prototype of the character was Khabarovsk resident Liya Kuzmitskaya-Knyazeva. However, that is an artistic narrative. And the captain prefers to talk about his life without embellishment. And he can’t tell everything - after all, he still remains the keeper of international state secrets.

Chinese letter

Ibu ibu de dao moodi,” Lapodush says. - Do you know what this means in Chinese? - he asks us.

We are embarrassed. What kind of half-matters is this writer suddenly planning to surprise us with?!

The Chinese have a saying. In Russian it sounds like this: “Step by step towards the intended goal,” answers Georgy Tomovich. - The first time I heard it was in 1973 at the negotiating table in Heihe (the Manchurian name for Sakhalin) in China, opposite Blagoveshchensk. And my ears turned red. This was at a time when river navigators were turned into diplomats. A total of 28 people took part in the negotiations, 14 from each side. The Soviet composition of the commission also included advisers from the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the KGB. This commission was formed in 1951 and worked under the auspices of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

For thirteen years, from 1973 to 1986, Georgy Lapodush was part of the Soviet delegation of the Mixed Soviet-Chinese Commission on Navigation on Border Rivers.

I have been with the Amur Shipping Company since 1943,” Georgy Lapodush tells us without hiding. - A quarter of a century on board. After graduating from the Blagoveshchensk River School, he worked as a navigator, then as an assistant captain, and in 1958 he became a captain. For eight years - until 1968 - he worked as a captain (he was the first!) on the motor ship Vasily Poyarkov. He was also the head of the shipping inspection. And even after retiring, he held the position of captain-inspector for seven years. Then he switched to onshore work. I started writing.

Man's destiny

As Georgy Lapodush writes in his autobiographical narrative, he was born as the fifth child in a poor peasant family in the Barabinsky steppes of the Novosibirsk region. In early childhood he became blind from the then widespread disease scrofula. Doctors predicted lifelong blindness. Cured by a wandering saddler-shoemaker.

Father - Tom Vasilyevich LOpAdush (as the surname is written on the certificate of rehabilitation) was arrested in 1937, recognized as an “enemy of the people,” although he could not sign his name in Russian and pronounced the school grade “satisfactory” as “satisfactory.” He had been a prisoner of war since the First World War, was of Romanian nationality and did not even have Russian citizenship. Mother - Maria Innokentyevna Lapodush, by her first husband Bobrovskaya, was the daughter of a wealthy peasant - Innokenty Nikitich Grebenshchikov, who had his own mill, but, without sufficient education and any profession, could not support the family.

After my father’s arrest, our neighbor Spirka, taking advantage of the misfortune that had befallen our family, gave a deposit and persuaded my mother to sell him our only asset, our breadwinner, my beloved and devoted friend, the horse Igrenka (my father earned his living as a driver). Soon he managed to break his leg, brought a horse on three legs and demanded that the deposit be returned, recalls Georgy Lapodush. “I will remember for the rest of my life how my mother tore her hair out of repeated grief and despair.

My childhood heart was filled with hatred for this neighbor, and I did not know how to take revenge on him for deceiving my mother and the death of Igrenka. I started doing damage in his garden. And he set a trap: he filled the boards with nails and laid them out on potato tops along the fence. Jumping with both feet onto the nails, experiencing incredible pain, I freed myself from the board and made my way to the house on my knees. Following the trail of blood, Spirka’s wife came to gloat at the moment when my mother placed in front of me a blazing hot semolina porridge, which I threw at my neighbor’s aunt’s face. The burn began to form an eyesore on her, and Spirka vowed to kill me...

|

Either out of the mother’s fear for her son’s life, or from people’s hostility towards the family of the “enemy of the people,” the Lapodushis left for Transbaikalia, to the gold mines in the city of Baley (Transbaikal Territory).

Soon the Lapodush brothers were sent to the front one after another. George had to quit school and go to work in order to somehow feed himself and his mother, who had become disabled. He got a job in a topographical party, and then, at the end of the season, was transferred to a mine as a sampler.

When they began to call up young people born in the 25th year, Gosha Lapodush, together with his friend Sashka Gilev, scraped their passports, turning six into five, and managed to get red summons, for which they immediately received payment. But at the military registration and enlistment office the fake was exposed. We got a job again, but this time at a gold recovery factory (GRF) - as a mechanic's apprentice.

In 1943, Georgy Lapodush went to enroll in the Blagoveshchensk Mining College, but under more favorable conditions (without exams), lured by naval romance, he entered the water technical school, transformed in 1944 into a paramilitary-type river school, which trained specialists for river transport and reserve officers Navy.

Before the start of classes, I was sent to Khabarovsk, and the personnel department of the Nizhne-Amur Shipping Company appointed me as a sailor on the tugboat Arkhangelsk, commanded by Captain Prodanov,” recalls Georgy Lapodush. - Eight hundred grams of bread, forty grams of cereal and ten grams of fat made up the daily diet. This was not enough for a working person. And when these products ran out during a protracted voyage, people were swollen from hunger, but they worked with all their might for the sake of victory.

The main and most exhausting work on the ship was related to fuel (wood, coal). Bunkering - fuel intake - was emergency (universal) work. Firewood was carried on shoulder straps from the shore to the ship and they filled the bunker and all free places on the deck and in the passages. Coal was loaded in ports by wheelbarrows into bunkers and boxes constructed from gangways in the bow and stern parts of the deck. And they replenished the coal already on the way from the hold of the barge. Coolies weighing 60-80 kg had to be pulled out of the hold along a ladder, brought onto the ship and poured into a bunker or box. The slightest delay provoked the ire of the stokers, who threw coal into the furnace of the steam boilers. The steamship burned forty or more tons of coal per day.

In 1945, during the war with Japan, Lapodush, while in practice as a second mate, carried out assignments from the military command, towing landing craft and barges with military cargo along the Sungari, from the village of Nizhne-Leninskoye to Harbin. In 1947, Georgy Lapodush, having graduated from a river school with a degree in navigator, went again to the Amur. In 1957, he became the captain of the steamship "Kutuzov", and a year later he moved to the steamship "Ilyich".

Man and steamboat

|

The fate of a steamship, like that of a person, can be very interesting,” says Georgy Lapodush, an honorary worker of the river fleet of the RSFSR, an honored riverman of the Amur. - For example, in 1894, parts of three towing steamships manufactured in Belgium from the John Cockerill shipyards, which were assembled in Sofiysk, were delivered to the Amur (later they received the names: “Ilyich”, “Sergey Lazo”, “Rosa Luxemburg” ). So, the steamship “Ilyich” was built by a Belgian company as a gift to the Amur Shipping Company with the condition that it would bear the name of the company. Before the revolution, it was called “John Cockerill” and was considered the flagship of the passenger fleet on the Amur. Then the comfortable “John Cockeril” became “Ilyich”, and another tug-and-cargo-passenger steamer “Baron Korf” - first “Leon Trotsky”, and then “Comintern”. It was on it that on May 10, 1932 the first volunteers arrived in the village. Perm, to build the city of Youth - Komsomolsk-on-Amur. These are the stories.

|

Georgy Lapodush became interested in the history of steamships, and then people, already in retirement. In 1999, his first book, “Amur Diplomats: Notes of an Amur Riverman,” was published. It is dedicated to the relationship between the two original neighbors on the Amur - Russia and China - in the most difficult times for the two countries, when a “mutual coldness” in relations led to acute border conflicts, including on the Damansky Islands (March 2–15, 1969) and Goldinsky - in the area of direction sign No. 114 (July 8, 1969).

For this book, the writer was awarded personal gratitude from the governor of the region, Viktor Ishaev. Next, Lapodush presented new books to the audience. First, he wrote a memoir, “In the Name of What,” about river life. There, by the way, he told the little-known story of the friendship of the singer Kola Belda with the Amur captain Vasily Panyushev. Then the books “Dislocation of the Soul”, “Premise” and “Earthly Destiny” were published.

But, as Georgy Lapodush assures, he has not yet written the most important thing.

Konstantin Pronyakin, Irina Kharitonova,

"Khabarovsk Express", No. 47.

Continuing the theme of old wheeled ships, I want to show you another ship I found. It would be more accurate to say that it was not found by me, but rather discovered for myself, and now for you, if you have not seen it yet. The first time I noticed it was last year, when on a sunny February day we made an outing to the village of Rozhdestveno. That time we did not approach and examine it, and the purpose of the walk was rather to see the village. But the ship has sunk into our souls since then, and now, a year later, the Volga ice is under our feet again, and driven by the wind we are again walking along the Volga towards the old paddle steamer, which is like a magnet attracting.

In general, walks on the Volga ice always give a lot of impressions. On a sunny weekend there are a lot of people walking here, and this is not surprising. After all, from here an excellent panoramic view of the city opens up, here you can catch your breath from the city smog, and standing somewhere in the middle, it’s worth imagining that such a colossal mass of water is moving under this 35-centimeter crust, and either from the realization of this, or from the freezing wind that has rushed across a cold chill runs through the body. But during these walks you seem to be charged with some kind of energy, as if drawing it from a river.

So admiring the winter landscapes, we passed through the Volga and the island. Here, on the banks of the Volozhka, 3.5 kilometers from Samara, on the territory of the tourist center, is the same old steamship that was the goal of our walk.

This ship is located on the territory of the TTU tourist center; a watchman’s house has been built on the deck, which is why it has not yet been sawed up and demolished to a scrap metal collection point. Several bridges lead to the ship; apparently, it is used for economic purposes.

An old steam tug, the brainchild of the Krasnoye Sormovo plant. In the early 30s of the last century, this plant produced a series of tugs with a capacity of 1,200 horsepower. At that time these were the most powerful serial tugs on the Volga. The first series of such tugs were: “Red Miner”, “Industrialization” and “Collectivization”. They were intended for driving oil barges with a carrying capacity of 8 and 12 thousand tons along the Volga. Only the “Stepan Razin”, the former “Rededya, Prince of Kosogsky”, which was built before the revolution in 1889 and had a power of 1600 horsepower, surpassed them in power. These tugs ran on fuel oil, were equipped with an inclined steam engine with two boilers and superheaters, the total heating surface of the boilers was 400 m2. The use of superheated steam made it possible to significantly increase the efficiency of the steam plant. A steam installation with three-stage water heating, that is, water was supplied to the boilers through heaters that received heat from already exhausted steam. The ship had an electric lighting network, the electricity for which was generated by a 14 kW steam dynamo, providing a direct current of 115 V. To lift anchors from the ground, the ships were equipped with a steam windlass at the bow of the ship and a stern capstan. In addition, they had a horizontal steering machine. For the first time in the river fleet, a steam towing winch was installed, on the drum of which almost half a kilometer of strong steel cable was laid. The machine and boilers, like all the ship's equipment, were designed and manufactured at the Krasnoe Sormovo plant.

The hull of the ships of the first series was riveted and was divided by nine bulkheads into ten compartments: in the first, bow compartment there is a pantry and a box with anchor chains; in the second there are cabins for sailors; the third is a rubber dam, which serves to prevent the penetration of gases from the fuel compartment; in the fourth there is a tank with fuel oil; the fifth was the engine room; in the sixth boiler room; in the seventh there is an aft fuel tank, then again a cofferdam, behind which are the cabins of oilers and stokers, and the aft compartment, where the stern anchor chains and machine parts were located. In the casing rooms, which are located on the outskirts next to the paddle wheel arch, there are cabins: two pilots, a driver and two assistants, a spare cabin, a red corner, a dining room, a laundry room, and a bathroom. The kitchen and dryer are placed in front of the boiler casing.

The forward deck house houses the cabins of the commander, his assistant, one pilot, and one radio control room. On the left side you can see inscriptions on the doors of the captain and the radio room.

The paddle wheels have been dismantled, so I’ll just show their diagram. The wheels had a diameter of 4.8 meters; each wheel had 8 metal plates - blades. To reduce energy losses when the plates enter and exit the water, they are made rotary, due to a hinged connection with an eccentric mechanism that regulates the position of the plates when the wheel is turned.

This wheel design has greater efficiency, ensuring that the blades enter the water at large angles of attack. The performance qualities of the new tugboats were significantly higher than those of pre-revolutionary vessels of similar power.

But along with all these technical advantages, the new tug had a number of significant shortcomings, which were identified after the “Red Shakhtar” tug was put into operation. Then the customer, which was the People's Commissariat of Water Transport, made claims against the plant. For example, when moving with a load, the ship did not obey the rudder well. It was found that the poor handling and longitudinal instability of the vessel was a consequence of an incorrectly designed hull, it was too narrow, the towing hook was too high, and the wheels were too offset towards the bow of the vessel. On the tugboats of the next series, these defects were eliminated, but on the already released ships “Industrialization” and “Collectivization” the changes were partially affected and the shortcomings regarding the hull design remained.

By 1936, the plant built a series of tugs of the Tsiolkovsky type according to the same project, with some changes relating, in particular, to the hull of the vessel.

Drawing by Mikhail Petrovsky taken from the website of the magazine Tekhnika Molodezhi

An interesting article about them was published in the 8th issue of the magazine Tekhnika Molodezhi for 1982, from where I learned a lot of useful information about the ship.

Through the snowdrifts, having filled my boots with a fair amount of snow, I walked close to the ship. Here there is no snow at all under the rampart, and the height of the side allows you to move freely without touching your head on the support brackets, of which there are many. The arch of the paddle wheel is closed; instead of a shaft, a channel is installed, which serves as a support for the decking, which just covers it. But you can carefully examine the structure of the body.

This design of the body kit, namely support on triangular brackets resting on the hull, was used on the first three ships: “Red Miner”, “Industrialization” and “Collectivization” and created some problems. The fact is that the water thrown by the wheel hit the brackets, thereby creating additional resistance to movement. On the vessels of the next series, the design of the outrigger supports was changed. The brackets began to be made in the form of beams suspended from vertical posts installed on the deck, and the ship's hull was made entirely welded; these changes made it possible to reduce the water resistance experienced when the ship moves.

This means that this tug is one of the first trinity of 1200 strong.

Having examined the hull, it turned out that it was welded, but with noticeable traces of alteration; the portholes were previously located lower on board; you can see their welded openings and were moved higher relative to the waterline.

It should be noted that the 30s were restoration years for shipbuilding, the industry lacked qualified personnel, and there were no research developments. On the river, pre-revolutionary vessels were mainly used; they were often converted for new tasks.

In terms of overall hull dimensions, the steamer is also very similar to the first series of tugs. Thus, the lead steamship of the first series, “Red Miner,” had dimensions of 65 x 9.8 x 3.2 m, which coincides with the dimensions of our oil tanker, the dimensions of which were measured, very approximately, on a map. However, they are the same. By the way, the width is given without taking into account the run-ins, along the waterline.

I went up to the deck, but did not approach the guardhouse, somehow I didn’t want to get caught by the watchman, I don’t think that my interest in the ship would have aroused his approval. Perhaps there are storage facilities here, and here I am without an invitation. Although I really wanted to see it, I didn’t get impudent; maybe I’ll come back here in the summer, when the tourist center is open and I can pass for a vacationer.

I walked around the ship, and the markings of the ship's draft scale were still visible on the rusting hull.

Looking through the forums of lovers of such river antiquities, I often came across the opinion that this is the tugboat “Industrialization”; there are very strong similarities with the surviving photographs of it, and the dimensions, the design of the outrigger supports, the number of windows on the deck superstructure - all this only confirms that this is definitely one of the first 1200 strong Sormovo paddle steamers.

One fact confused me. On the arch of the left paddle wheel, the one located on the side of the camp site, the numbers “1918” and the letters at the top of the arc, either “rn” or “ra”, are barely visible. Paint stains, its layers showing through one another and the ongoing corrosion make it difficult to make out the full name of the ship. I tried to search for ships with a combination of these letters and numbers on the Internet, unfortunately, the search did not give any results.

Perhaps it was renamed, but this is only an assumption, because I have never seen any mention of the renaming of tugboats from the first three, except for the first-born. Only “Red Shakhtar” was renamed “Georgiy Dimitrov”.

A porthole was open next to the propeller shaft axis support. With the hope of seeing at least some preserved part of the steam engine, I looked inside. Pitch darkness, only the luminous circles of portholes on the opposite side were visible, through which light passed and immediately dissolved in the darkness. Having raised the iso fairly high, I stuck my hand with the camera inside and took a few shots.

If you look closely, you will notice that the connection of the structural elements inside the body remains riveted.

Then I turned on the flash and clicked a few more times. There was a noise somewhere nearby. I listened, everything became quiet. But he didn’t put the camera in the porthole anymore. Walking along the hull of the ship, I again heard a creak coming from inside. Yeah, that means I didn’t go unnoticed and attracted someone’s attention. However, no one came out. Oh well, hopefully I'll be back next time the snow melts.

As he was leaving, he looked back to take another look at this river rarity, worthy of becoming a museum exhibit of the river fleet.

In the history of the formation of the Russian state as a whole, and the vast region of the Far East in particular, it is impossible to overestimate the exceptional importance of waterways, the development of which is directly related to the formation of a single centralized Russian state and the development of its economy. At one time, the settlement of river systems, spaces adjacent to rivers and lakes, movement along them as the main means of communication, served as the basis for the very settlement of the Slavic tribes that formed the Old Russian people.

...

In Russia's exploration of the Far East, which began in the 17th century with the expeditions of Vasily Poyarkov, Erofey Khabarov, Alexei Tolbuzin and other explorers, the Amur River was of utmost importance, the main one until 1916-1917. (when the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway along the Amur was completed and the largest bridge “Name of Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich” was introduced near Khabarovsk) is almost the only transport communication connecting all the cities, Cossack and peasant settlements of the Amur region, annexed to the Russian Empire along Aigunsky (16.5. 1858), Tianjin (13.6.1858), Beijing (15.4. and 4.11.1860) and subsequent St. Petersburg (12.2.1881) treaties with the Chinese Empire, thanks to the efforts, first of all, of the Governor-General of Eastern Siberia in 1847-61. N.N. Muravyov (who received the honorary title “Count Muravyov-Amursky” on August 26, 1858 for his successful actions in securing the region), as well as admirals G.I. Nevelsky and P.V. Kazakevich, diplomats E.V. Putyatin, Count P.N. Ignatiev and other figures of that time.

...

The Amur River (from the local name E-mur), one of the largest rivers of our Motherland and the only one in Siberia and the Far East, carrying its waters not from south to north, but from west to east, extends from Ust-Strelka, the place of its formal the reference point where the Shilka and Argun rivers merge is 2824 km, and from the source of the Argun in the Chinese Hailar region - 4440 km; is considered stably navigable from the mouth (96 km below the city of Nikolaevsk-on-Amur) and to the city of Sretensk on the Shilka River at a distance of up to 3052 km (although in some years shallow-draft steamships - see Chapter II - rose even higher, along tributary of the Shilka - the Nerche River directly to the city of Nerchinsk, and one steam boat in 1863 - see Chapter VII - even reached Chita). The Amur River itself is divided by some authors into three sections, each of which has its own natural geographical features, periods of freezing/breaking, etc.: the upper reach, from Ust-Strelka to the city of Blagoveshchensk - 898 km, the middle one, from it to the city of Khabarovsk, 987 km (both sections are border with China) and the lower one, to Nikolaevsk-on-Amur, its bar (rift) and the confluence with the Tatar Strait - 933 km. The most important tributaries of the Amur from the left (Russian) bank are the Zeya River (with the tributaries Selemdzha, Bryanta, Gilyuy, Tom, Urkan, etc., which gave names to many Amur steamships), Bureya, Urmi, Amgun and many smaller ones, such as Bira and Bijan; from the right bank - the Selenga River (China, and at the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th centuries - in the joint shipping use of China and Russia, and then mainly by Russian steamships) and the Ussuri River with the tributary of the Sungacha (border with China), with the tributaries of the Bikin, Khor, etc. It seems more correct to divide the Amur into the Upper Amur, from Ust-Strelka, past Blagoveshchensk and to the confluence of the deep Sungari River, almost opposite the village of Mikhailo-Semenovskaya (now Leninskoye), 1655 km, and into the Lower Amur, from it and to the Tatar Strait, 1169 km, which, in fact, was the place of delimitation of the “areas of responsibility” of the WARP and NARP shipping companies, established on December 21, 1936.

The total area of the Amur basin is 1855 thousand km 2 (more than the area of the largest continental states of Europe - France, Spain, Germany and Italy, combined, 1714 thousand km 2), while approximately 2/3 of the area of the Amur basin falls on the territory Russia. ...

The rapid settlement by Russians of a hitherto sparsely populated region, inhabited not so much by the Chinese as by Golds, Tungus and other local peoples, which began in 1854-55. from the famous "rafting" of Cossacks and settlers down the Amur (see Chapter I), its constant connection with European Russia was carried out from two directions: from the west by land, through Transbaikalia, Chita and Sretensk, where horse-drawn roads led, and the Trans-Siberian Railway was carried out in 1899 (and further down the Amur by steamships and barges), and from the east, through the ports of Nikolaevsk (founded in 1858, since the end of the 19th century informally called Nikolaevsk-on-Amur, and officially since 1926 .) and Vladivostok, established in 1860 as a center for the development of the Eastern (by the name of that time) ocean, which since 1872 has become the main military and commercial Russian port on it, as well as initially Okhotsk, connected by a highway with Yakutsk and through it with Irkutsk , - the first base of the Russian fleet in the Pacific Ocean.

Since the middle of the 19th century, all kinds of goods, products, tools and building materials, as well as settlers and troops necessary to consolidate the region, arrived in these ports by sea and in ever-increasing quantities, first on “state-owned” steamship transport ships of the Baltic Fleet and the Kamchatka Flotilla, and after 1878 - on the ships of the newly established semi-state Voluntary Fleet, on private ships ROPiT, RVAZOP and other joint-stock companies; in addition, a certain part of the goods was brought to the same ports, especially in the initial period of duty-free import, from neighboring countries, mainly from the USA and China, less - from Japan, as well as from Germany, England and other European countries. All these goods were then transported during the six-month summer navigation up the Amur River (already against the current) and down the Ussuri River on steamships and barges, and in the winter, in conditions of impassable taiga, close to the coastline, again along the Amur River and its tributaries, now along winter sled roads laid on ice up to 1.5 m thick (which, as it turned out later, could also withstand railway cars rolled by horse-drawn vehicles on temporary rails and extended sleepers).

The construction of the Russian so-called on the territory of Manchuria was also of great importance for the development of the Amur region. The Chinese Eastern Railway (CER), begun in 1897, completed in 1903 and connected with the previously isolated Ussuriysk Railway, carried initially from Vladivostok to the Iman station and pier, and then in 1899 brought to Khabarovsk, connecting the Trans-Siberian Railway through China with Vladivostok, and the significant water transportation associated with this major construction along the Ussuri, Amur and Sungari of materials for it (rails, sleepers, bridge structures, then steam locomotives and cars); At the same time, the city of Harbin, founded by the Russians in 1898 at the intersection of the projected railway and the Sungari River, acquired special significance, from where Chinese goods had long been transported in the opposite direction by Russian steamships downstream to the Amur, starting with single voyages in 1864. (see Chapter VIII), which became regular since 1896. At the same time, the construction of the CER itself was carried out in 1897-1900, 1902-1903. from three directions: from the west from Transbaikalia, from the already operating Manchuria railway station, from the east, from the Pogranichnaya railway station near Vladivostok, and “from the center” of the route and further in both directions towards the two end sections from the city of Harbin, in which all cargo and construction materials arrived exclusively by water, on ships and barges of a large, specially organized flotilla of the CER, as well as on dozens of private ships chartered by the road construction department, along the route: port of departure, Pacific Ocean, port of Vladivostok, then along the Ussuriysk railway to the Iman pier (now Dalnerechensk), then only along the river system - along the river. Sungache and Ussuri to the Amur, along it to the station of Mikhailo-Semenovskaya and further along the Sungari river to Harbin. ...

The shipping company on the Amur arose in 1854 and initially all Amur steamships were military transport and “state-owned”, belonging to the Military (“Land”), Maritime, Telegraph (Ministry of Internal Affairs) and other departments, although all of them, along with the steamships of the Russian-American Company , who entered the Lower Amur, actively participated in the economic development of the region and stimulated the development of its economy. The first commercial steamship appeared in the basin in 1859 (see Chapter II), and in 1860 it made a long voyage from Nikolaevsk[-on-Amur] to the upper reaches, reaching the Shilka river to the village of Sretensky and even higher - to the city . Nerchinsk. It was followed by the ships of the Amur Company and private individuals (at first - foreigners, but who accepted Russian citizenship, and all the ships sailed under the Russian commercial flag); in 1871, the Amur Shipping Company Partnership (TAP), subsidized by the state, was established, and in 1872, it opened its operations with obligations to transport government and private mail, troops and the regional administration with the corresponding cargo (for a fee, but at reduced rates ); Since 1894, an even larger government-subsidized shipping company, the Amur Shipping and Trade Society (AOPiT), began operating with its board in St. Petersburg. In parallel, the private unsubsidized fleet of local merchants and industrialists was rapidly developing, commercial shipping companies and societies were established (especially after the opening of gold mines in the mid-1860s, when enterprises such as the Upper Amur, Zeysko-Selemdzhinsk and later Amgun gold mining companies were formed, the partnerships of Eltsov and Levashov, Alfons and Lydia Shanyavsky and many others, who transported mine workers on their ships in the spring and picked them up in the late autumn), the purely private fleet of indigenous Amur shipowners grew rapidly; entire dynasties of “steamship operators” arose, which at the beginning of the 20th century, in contrast to the successful AOPiT and TAP, which was collapsing after the end of subsidies, united into syndicates and trusts with the names “Bystrokhod”, “Bystrolet”, “Amur-Shilkinsky Express”, “Sungari Express” etc., which in 1916 culminated in the organization of the largest association on an all-Amur scale - the Partnership - Amur Fleet (TAF), which dictated its monopolistic high tariffs, for which part of the Amur commercial ships included in TAF were even laid up, with issuance to shipowners from the board of their respective compensations.

A shipping fee for shipowners on the Amur (to create a system of river “furnishings”, that is, buoys, milestones, bank markings, as well as to begin clearing fairways) was established in 1886; Since 1894, the shipping inspection of the Ministry of Railways began to operate (initially - under the flotilla of the Ministry of Railways on the construction of the Trans-Baikal Railway), transformed in 1898 into a separate Directorate of Waterways of the Amur Basin (UVP AmB) under the Ministry of Railways, which quickly established a large flotilla of inspection, situation, firemen and other service ships and boats, as well as 5 dredgers with tugs, dredging scows, barges and fire guards with them. UVP AmB from 1898 to 1910. successively headed by L.M. Valuev, general/m. A.A.Berezovsky, book. M.M.Dolgorukov, from 1911 - engineer. P.P. Chubinsky, in 1918 - N.G. Berezin, in 1919 - N.P. Krynin, who did a lot to develop navigation on the Amur and improve its conditions, through deepening and marking fairways, developing and maintaining water and coastal conditions, vessel registration, etc.

Own shipbuilding on the Amur developed slowly, especially in the 19th century. The metal hulls of Amur ships (iron, then steel) until the beginning of the 20th century were imported (from Germany, England, the USA, Holland; later, en masse, from Belgium; in smaller quantities - from shipyards in the European part of Russia and from Tyumen) ; they gathered mainly in Nikolaevsk[-on-Amur] and in the village of Iman (foreign), occasionally - in Sofia, Mago, Mariinsk and Khabarovsk, separately - in the area of Sretensk, Nerchinsk and Kokuy (Russian, delivered through Siberia); after the introduction of the Chinese Eastern Railway, some Russian steamships also began to assemble in Harbin and then float down the Sungari; all mechanisms for steamships (steam engines, boilers, paddle wheels and other equipment, including electrical) - until the end of the 19th century. were imported, mostly from abroad. The wooden hulls of steamships and barges, which respectively accounted for about 2/3 and 4/5 of the entire private Amur fleet, were built on site, mainly in Sretensk, Blagoveshchensk, Khabarovsk, the villages of Astrakhanovka, Surazhevka, etc. Since the beginning of the 20th century, in addition to wooden, Local metal hull shipbuilding began to develop, as well as the production of mechanisms, primarily steam boilers, then steam engines: the factories of S. Shadrin and I. Chepurin with A. Afanasyev appeared in Blagoveshchensk (and there were repair shops of UVP AmB in " Ministerial Zaton", in addition to repairs, also built small ships), R. Chelgren near Khabarovsk, D. Kuznets in the village of Kokuy on Shilka, as well as branches of shipbuilding plants from the European part of Russia - Tyumen, Votkinsk, then Sormovsky, which not only assembled steamships from blank sections produced by their factories, but also carried out the primary construction of ships made of sheet steel and rolled products, delivered via the Trans-Siberian railway; The assembly of 10 gunboats and 8 four-tower “monitors” of the AKF, carried out in 1907 and 1909-10, was of great importance for the development of local industry. branches of the Sormovo and St. Petersburg Baltic factories in Kokuy, with their completion and armament in Khabarovsk. The superstructures of all the ships were wooden, built on site, but often - for luxury passenger ships - with the use of imported expensive types of wood, "overseas" finishing fabrics and leather, brass and then rare chrome-plated parts, etc. in the interiors.

In terms of naval architecture on the Amur in the 19th century, single-deck steamships predominated, both towing (all) and passenger (most), although among them there were also single double-decks, starting with the first commercial steamship (see Chapter II) and such, according to local on the scale of that time, giants like the “losers” of TAP of the 1880s, the slow-moving “Ermak” and “Vestnik”. Since its appearance in 1908, then in 1912-13. high-speed and comfortable double-deck steamships "Sormovo", "Votkinsky", "Lux", "Kanavino" and others. Not only began the mass construction of ships of this type, but also the reconstruction by shipowners of old single-deck steamships into double-deck ones to increase their passenger capacity. (As far as we know, there were no three-deck steamships on the Amur not only in the pre-revolutionary, but also in the pre-war periods; they appeared already in the “motor ship” era, in the 1970s).

Based on the type of propulsion that determined the appearance of the vessel, the vast majority of towing steamers were “two-wheeled” (with side paddle wheels) and wide bulwarks (the main deck overhanging the water), so that their greatest width along the deck was almost twice the width along the waterline; There were few screw tugs with a deeper draft and they were used only on the Lower Amur, where greater depths allowed their use. Passenger (cargo-passenger) steamships were both “two-wheeled” and “single-wheeled,” that is, with a rear paddle wheel; among the latter, for a long time, the archival type (dating back to the first steamship of R. Fulton) was maintained, when the steam engine was located at the stern, and the steam boiler with a chimney was at the very bow of the ship, on the deck; Such a general arrangement of mechanisms had the advantage that it more evenly distributed heavy loads on the ship’s hull, making it possible to reduce its height, but also several significant disadvantages: an increase in the length of the steam line stretched from the boiler to the engine through the entire steamer (and, accordingly, loss of power, as well as an increase in fuel consumption), crowding and overheating of the “transit” rooms in the summer (although the steam pipeline, of course, was lined), and most importantly, the deterioration of the view from the wheelhouse, which was forced to be located... behind a tall one and “spewing out” clouds of smoke, soot and sparks bow chimney. To increase the longitudinal strength of the hull without increasing the draft, many “one-wheeled” steamships had a system of external trusses, superimposed on the superstructure, with diagonal metal strings; they, like the “two-wheelers,” had drifts, but of a smaller size, and sometimes, like them, the “rear-wheelers” even engaged in driving barges, but not leading them behind them on towing ropes, but tightly mooring them to their sides, which did not receive mass distribution, as it sharply reduced the speed and worsened the maneuvering qualities (already low) of the rear-wheel steamers themselves.

The number of chimneys on all Amur ships did not exceed two per ship (not like in the Russian navy, where there were several dozen three-tube ships, 8 four-tube cruisers and battleships, and three dozen destroyers, and the record holder for the “chimney capacity”, the cruiser "Askold" even had five tall chimneys, nicknamed "pasta" by the sailors); Most of the chimneys on the two-pipe steamships of the Amur were located in the center plane, one behind the other, although there were a few steamships of the “American” system, with two pipes located across the hull. The number of pipes, as a rule, corresponded to the number of steam boilers and their furnaces; there were only a few cases of “transfers” of chimneys and combining several of them into a common chimney (universal on large warships) on the Amur: for example, the large towing steamer UVP AmB “Khabarovsk”, the future - see below - “Rabochiy (2nd )" (which had four steam boilers) and the private passenger "Vasily Alekseev", the future "Harbin" (three boilers) in their "silhouette formula", taking into account the number of pipes and masts, masked the number of boilers, hiding their boiler "secrets" by internal transfer of chimneys and externally revealing, respectively, only two and one chimneys. (In addition to the “main” chimneys, many passenger ships also had a “small” chimney from the firebox of the stove in the galley, but this contrasted so clearly with the large “running” chimneys that it may not be taken into account in the description of their number on the ship).

Unfortunately, the censuses of river vessels did not record either the number of steamship chimneys or the number of decks (sometimes, see above, which increased over time during reconstruction), so, without having reliable photographs with a discernible side inscription (which still need to be “linked”) "to ships with numerous identical names), it is no longer possible to restore such characteristics.

Until the end of the 19th century, Amur steamships were heated with cheap “local” fuel, that is, they ran... on freshly cut wood. Moreover, in the 1850-1860s, there was a wild practice, from a modern point of view, when every evening a regular steamship would stop near the shore (steamships did not sail at night then, due to the lack of searchlights on them, and on the water and on the shore - the shipping “situation ") and its crew - and sometimes some of the male passengers - landed on land on ship's boats, cutting down nearby trees, immediately sawing them into logs of a certain length and transporting them to their ship, where they were then split into logs and burned in boiler fireboxes stokers. Since the 1870s, an improvement arose, a kind of folk craft: cutting down nearby forests and preparing logs of strictly defined lengths for steamships, according to the “measure” (including in winter, for future use, bringing logs of wood on sleighs) were not sailors and stokers from steamships, and local Cossacks and peasants (as well as aborigines), they also built, near their huge woodpiles, if not piers, then temporary bridges, to which steamships began to moor as “bunker bases”, and the duties of the crew now included only reloading the fuel prepared in advance , for which, previously completely free, now steamship captains had to pay for each cubic fathom; at the same time, they paid not only with money, but also with some goods that they specially took with them on the flight (such as fire supplies for hunting rifles, soap, matches and kerosene for lighting, and scarce products such as salt, sugar, tea and, of course , alcohol - let’s not idealize anything; however, it was mainly “foreigners” who were drunk with alcohol: Cossacks and “Old Believers” peasants tried to abstain from it).

By the way, among steamship stokers from the beginning of the 20th century. the Chinese and Koreans began to predominate - strong, hardy and, what is especially important for cramped and low stokers, short, and they were paid less; They tried not to recruit Russian big men a fathom tall into stokers; they assigned them to deck sailors, then transferring the literate and intelligent ones to helmsmen; local teenagers were recruited as “maslenschiki” (assistant mechanics), the most intelligent of whom then grew into steamship mechanics (then called machinists); from the end of the 19th century On the Amur river schools also appeared for helmsmen (future practical captains) and steamship drivers, and later for motorists of the first ships with internal combustion engines.

With such a barbaric initial method of providing ships with fuel - massive cutting down of forests along the Amur itself and other navigable rivers - for the steamship owners themselves, it had two clear advantages: a sharp reduction in bunkering time and partial preliminary drying of the firewood itself, covered in woodpiles with spruce branches, and for the development of the Amur edges is also the fact that along the rivers, in place of the impassable taiga, which previously approached the water closely, the first permanent roads began to appear, and places were also cleared for laying telegraph lines made of copper-plated wire on wooden poles, which (see Chapters VII and VIII) were built and then serviced “from the water” by four (then six, Chapter X) steamships and steam boats of the Telegraph Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs specially purchased for these purposes. To transfer telegraph lines across numerous transverse tributaries of the Amur, openwork wooden towers were built, sometimes unique (for example, when crossing the Amgun River, the height of a 15-story building). At the same time, the lines themselves had to be systematically restored, since ordinary poles for them often fell, from the erosion of the shore or from strong winds, as well as from repeated cases of taiga bears climbing on them, attracted by the “buzzing” of the wires, which they probably mistaken for the hum of a swarm of bees; At first, there were also cases of poles being cut down by Old Believers settlers who were dissatisfied with the “demonic” innovations, which were stopped by the arrests of the perpetrators and soon stopped.

From the beginning of the 20th century, Amur steamships began to be converted to heating with hard coal, mainly from the Suchanskoye deposit, for which the grates of the steamship fireboxes had to be redone, but this quickly paid off by increasing the calorific value of coal compared to firewood, reducing the fire hazard and pollution of steamships, since the amount of soot and sparks sharply decreased , emitted from chimneys; The number of fires also decreased, because earlier, when heating with wood, they tried to dry it by keeping it directly in the fireboxes and even directly leaning it against the lining of the boilers. To create real bunkering stations, located along the entire Amur, they began to use coal barges, transporting them along the river by tugboats and anchoring them in convenient places.

The steam boilers themselves on the Amur were used of the fire tube type with a pressure initially from 2-3, then up to 10 atmospheres; references to water-tube boilers, which are more productive, but also more capricious, dangerous to operate and requiring highly qualified stokers, date back to the 20th century and are not very reliable; As far as is known, there were no boiler water desalination plants or “warm boxes” that allowed condensing steam and supplying residual hot water to the boilers on the Amur (including the gunboats of the AVF Maritime Department built in 1907).

The steam engines of the Amur steamships were initially single-cylinder, low-pressure, including “balancer”, “oscillating” and numerous other various systems, then - medium pressure; Already in the 1870s, machines of the “compound” (double-acting) system appeared and became widespread, in which the piston was pushed by steam, closed by “spool valves,” alternately on both sides, working either “pushing” or “pulling” crankshaft cranks; in the last quarter of the 19th century, steam engines with triple expansion of steam appeared en masse, with cylinders of high, medium and low pressure, respectively increasing in diameter, and also (in small quantities, only in a few powerful towing steamships of AOPiTa) with steam engines even with quadruple expansion (we do not know what the 2nd and 3rd cylinders of such machines were called, we suggest - “medium” and “semi-medium” expansion; of course, as a joke).

All Amur steamships had a steam engine, almost without exception. one, but - for two-wheelers - with a release clutch for the left and right paddle wheels, in order to improve the maneuverability of the vessel (they, as a rule, did not have reverse gear); two In the pre-revolutionary period, independent steam engines were available only on later twin-screw steamships on the Lower Amur. There are known cases when, if your wheel is damaged, mover the steamer got to the nearest pier “on one wheel”; A curious case is also described when, after a night stay near the shore, a small steamer could not at first “spin” its paddle wheels, because a bear climbed inside one of them in the shallow water and fell asleep, and then (severely dented) hobbled off into the taiga.

The steamship paddle wheels themselves initially had flat and rigidly fixed platters (paddles), and from the 1870s more and more - with sickle-shaped and, most importantly, rotary platters of Morgan's complex mechanical system (entering the water and exiting it vertically), which reduced unproductive splashing and sharply increasing the traction characteristics of the wheel. The system was expensive to manufacture and “capricious” to operate, but quickly caught on, as it paid off by increasing the speed of the steamship, reducing fuel consumption, a noticeable decrease in noise when the plates “spanked” on the water, and for tugboats - by a real increase in the number of barges trailed behind them and rafts, especially against the current.

At the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th centuries. the first ships with internal combustion engines (gasoline, naphtha, kerosene, and also those powered by crude oil) appeared on the Amur; initially these were only service and passenger motor boats, then - sailing-motor schooners, especially numerous on the Lower Amur, fishing in the estuary; by 1917, in the Amur basin there were already over a hundred motor boats of various departmental systems, “state-owned” and private (see here, in the table below).

The first ship on the Amur, built immediately as a motor ship, according to A.S. Pavlov [Pavlov, 1992, p. 61], was the single-screw towing motor boat "Ermak" (according to our data, the 3rd with this name in the basin, "Ermak "/3/), with an iron body, equipped with a 24 hp kerosene engine. the Otto Deutsch company from Cologne; according to our research, it was far from the first of the Amur motor boats and appeared in our basin around 1908-1909, belonging to Efimov and Arkadyev, and according to three further censuses of ships of 1911-1917, it was listed as belonging to A.K. Arkhipov, but it was purchased second-hand, since not only the engine, but also its body were built (in 1901) not on the Amur, but in Germany, in the same Cologne; however, it can be considered as the first Amur tug and cargo ship, larger than dozens of simply service and traveling motor boats of that time (with the exception of powerful armored boats of the "Pika" type of the AVF, 1910, domestic, built by the St. Petersburg Putilov plant), ch. .size "Ermaka" /3/ were 10.8 x 2.3/2.1 x 1.1 m; it survived the Civil War (according to indirect evidence, it was scuttled and then raised), and in the 1920s with the same name it was located at the Nikolaevsk-on-Amur seaport.

In 1913, the first “real” cargo and passenger motor ship, intended for regular voyages, appeared in the waters of the Amur, assembled in Harbin from the shipowner A. Kashirin from the old hull of 1881 and the new internal combustion engine of the Kolomna plant (Golutvin station, now within the boundaries of the modern "big" Kolomna, Moscow region), called "Borodino" (2nd on the Amur with this name). The same fleet historian A.S. Pavlov (Pavlov, 1992, p. 61) claims that earlier this first scheduled passenger ship on the Amur was called “Molodets”, and before that - “Askold”; Without refuting it, we point out that these names of its building are not primary, and the building itself was built for the Amur by a German factory back in 1861. One way or another, it is certain that the m/v "Borodino" burned out (without casualties) on June 13, 1913 due to a fire of its own internal combustion engine and, according to the same author, was dismantled in 1920; according to our sources (see Chapter VII, which contains - with sources - the whole history and version of the first name of this extraordinary ship), it was restored by 1923 again as a steamship, with an ordinary steam engine and sold to Chinese shipowners, from whom it received the name "Kwan-chan" was further mentioned with him in 1929, then owned by the Qiqihar Bank. So the first experience of own motor ship construction on the Amur turned out to be unsuccessful: too often the introduction of new technology was accompanied by accidents.

All the more difficult, with accidents and even casualties, as well as losses of steamships, was the development on the Amur of a seemingly not so difficult and for Russia as a whole not new, already mastered technology, such as oil heating of steam boilers, since oil is in The Far East had its own, Sakhalin. (On the Volga by 1917, thanks to the efforts of engineer V.G. Shukhov, known not only as the author of the first Moscow Television Tower, but also as the inventor of nozzles for injecting liquid fuel into boiler furnaces, the vast majority of steamships had already switched to heating with Baku oil). But the introduction of oil heating of boilers on the Amur in the pre-revolutionary period was delayed, and in Soviet times it was accompanied by many accidents that occurred with a small steamer, which then bore the sixth name in its “biography” - “Lenzatonets” (see attached Chapter IX), and with the most powerful of the Amur steamships, the tug "Rabochiy" (2nd) [formerly "Karl Marx" (2), "Burlak" (3), and initially - "Khabarovsk" (2) MPS], and with another, less powerful , ordinary tugboat "Moskva" (4) [formerly "Zinoviev", "Moskva" (2)", "General Linevich", "Nikolaevsk" (5), originally - "Vladimir Atlasov" TAPA], a constant "loser" who pleased subsequently had an even bigger accident, although not related to the boilers: on the night of 3/4/9/1932, going up the Amur from the village of Perm (now the city of Komsomolsk-on-Amur), 140 km from Khabarovsk, he collided with the towing steamer AGRP "Ivan Butin" [formerly "Stefan Levitsky", originally "Mikhail" (1)], as a result of which the latter sank irrevocably at great depths and with casualties (7 people from its crew died), and the BSF "Moscow" itself ( 4) received significant damage, but remained afloat, obviously for new major incidents (all about it in detail and with sources, see APPENDIX 3).

But the most serious accident, directly related to the conversion of a previously “coal” steamship for oil heating and the inept handling of young stokers (now listed as “boiler operators”) with its modernized boilers, was the death of a steam boiler explosion on the night of 12/13/11/1931 while towing. cargo-passenger ship "Trud" [formerly "Mikhail Mirrer", originally - "Nizhny Novgorod"], the victims of which were 15 people from its crew of 37 people. (hurrying for the winter and forcing the boilers, he, by coincidence, was already traveling without passengers - see Chapter I). So the introduction of oil heating of steamships on the Amur in the 1920s - early 1930s. occurred with great difficulties and was associated with many accidents and tragic incidents.

* * *

The increase in the number of Amur commercial self-propelled vessels on the Amur (without the “official” fleet of the MV, VV, UVP AmB and other departments of the Ministry of Railways, the Telegraph and Resettlement departments of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, etc.) according to A.S. Pavlov [Pavlov, 1992, p.60-61] in the pre-revolutionary period is characterized by the following indicators: in 1880 - 27 steamships, in 1895 - 56, in 1914 - 390 steamships, i.e. steam and motor ships together. According to our updated, but still preliminary data, which also takes into account all “state-owned” vessels, the number of “personally” identified self-propelled “pre-revolutionary” vessels on the Amur (which can then only be adjusted upward) was somewhat large and is presented below in tabular form, Where:

k1 - the number of "state-owned" steamships of all departments

k2 - the same, steam boats

k3 - the same, motor boats and (from the beginning of the twentieth century) passenger motor ships

k4 - Total, number of “state-owned” steam ships of all departments

ch1 - number of commercial ships (A/O and private)

ch2 - the same, steam boats

ch3 - the same, motor boats and (from the beginning of the twentieth century) passenger motor ships

ch4 - Total, number of commercial steam ships of all owners

с1 - TOTAL, the sum of "state-owned" and commercial ships

с2 - TOTAL, the sum of steam boats --"-- and --"--

c3 - TOTAL, sum of motor boats and passenger ships (--"--)

с4 - TOTAL, the total amount of “state-owned” and commercial steam ships

| At the end of the year |

|

|

|

Note |

|

|

|

|

4) |

| 1854-1917, total sailed at different times | 5) | |||

Notes:

1) The reduction in the number of steamships and p/c with a radical change in the structure between “state-owned” and private shipowners is explained by the fact that since the navigation of 1872, 3 steamships VV and MV and 1 p/k MV were sent to Vladivostok, and 9 steamships MV and 2 The telegraph departments, remaining on the Amur, were transferred to the new commercial TAP.

2) Including those sold to Chinese shipowners, but included in Russian censuses - 6 ships.

3) The same in the years - 19 p/x.

4) Dismantled due to dilapidation, after accidents; burned, sank irrevocably or raised but not resurrected; converted into barges; transported to other basins, incl. in World War I they were sent by rail to the European theater of operations, etc.

5) In addition, 7 steam non-self-propelled ships: 5 dredgers ("Am.-1" - "Am.-5"), and 2 passenger barges with p/machines for electric lighting

For more detailed information, starting from 1854, including the division of “state” steamships by main departments, and commercial ones by main shipping companies and types of owners, see Tables 1 and 2 (Chapter XI and Conclusion].

The strategic importance of the Amur as the most important military transport (although not large-scale) communication of the Russian Empire in the Far East was determined immediately after the formation of the Amur region, which was initially part of the East Siberian General Government (in 1884 it was separated into an independent one, with its center in Khabarovsk) and the Amur Military District (PrVO). This significance was especially evident in 1900-1901, when massive transportation (and in 1901-1903 - return evacuation) of Russian troops was carried out along the Amur River during the anti-colonial "Boxer" uprising in China, for which purpose they mobilized and even over a hundred steamships of the semi-state "Partnership of the Amur Shipping Company" and private shipowners were temporarily requisitioned, and an entire military flotilla was organized - "General Sakharov's Squadron", intended for the relief of the Russian population of Harbin, surrounded by rebels and Chinese troops (the composition of the "Squadron", established by us in many ways scattered documents, see APPENDIX 6); at the same time, there were no clashes with Chinese ships at that time, due to the absence of any in the military theater (local battles with armed Chinese sailing junks, as well as Chinese shelling of Russian ships in the Blagoveshchensk area - see Chapter VIII and APPENDIX 7 - and our retaliatory landings from steamships on the Amur in the Sakhalyan-Aigun area and on the Sungari in several settlements took place).

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. on the Amur, many commercial steamers were also chartered, mobilized and partially armed by the Military and Maritime Departments, but on a smaller scale than four years earlier (about 50), and some of them were transferred to the disposal of the ROKK (as tugboats of numerous hospital ships barges) and border guard OKPS; There were no battles with the Japanese directly on the Amur, but they took place on Chinese territory, where the entire Russian Liaocheng flotilla perished, incl. three small steamships of the CER company and several private ones; but, strictly speaking, the Liao-He River does not belong to the Amur basin.

During the fierce Civil War of 1918-1922. in the Amur basin (including on Shilka and far from it, on the Ussuri River), several “red” and “white” flotillas of commercial ships armed (most often with machine guns and rifles, occasionally with field guns) were organized, as well as individual gunboats, “monitors” and armored boats that remained combat-ready from the AAF, which by that time had been partially disarmed during World War I (with the sending of guns and mechanisms to the European theater of operations), partially self-scuttled by the crews due to the threat of capture by Japanese invaders, partially all captured by the Japanese; but it is characteristic that there were actually no battles BETWEEN ships or armed civilian vessels in the Amur basin, but there were numerous cases of “fleet action against the shore” (and reverse), in the form of shelling of steamships with field guns from land, shelling of army and Cossack units from “ red" ships, as well as cases of partisan attacks on "white" ships from the shore, with the destruction and burning of the latter (see APPENDICES 1, 3, 16).

Such REAL military operations of flotillas against flotillas, ships (and auxiliary vessels) against similar enemy forces took place on the Amur twice (without touching here on the clashes in the area of Damansky Island and other islands bordering the PRC in the post-war period), namely:

- in November-December 1929, during the so-called. “Conflict on the Chinese Eastern Railway”, when in response to the provocative arrests of Soviet employees of the Chinese Eastern Railway and members of their families, to the shelling by the “White Chinese” of our passenger and cargo ships on the Amur, ships of the Amur Military Flotilla (then still DVVF) and several mobilized civilian steamships of the AGRP, which defeated the Sungari flotilla of the "Great Empire of Manchukuo" (see APPENDIX 8), which consisted of both specially built gunboats ("cruisers") and armed steamers (mainly from former Russian "licensed" tugboats of the pre-revolutionary society of the CER), and also six Chinese steamships were interned, four of which were also of Russian origin, hijacked to China in 1918-22;

- in August 1945, during the Manchurian offensive operation of three fronts of the Red Army, with the participation of the Amur Red Banner Flotilla and a large number of mobilized civilian vessels WARP, NARP and AmBUP (see Chapter IX, list note 7), which ended - in relation to the river fleet - the surrender and subsequent capture in the Harbin area of the now Japanese Sungari flotilla, which consisted of 4 new Japanese gunboats, 17 combat boats, and more than 50 mobilized civilian ships, over a hundred barges and other non-self-propelled vessels , which belonged to the puppet pro-Japanese "empire" of Manchukuo, but - from civilian ships - mostly of Russian pre-revolutionary origin, stolen by Amur shipowners to China in 1918-1922, including the steamships of the former JSC CER that survived in 1929 ( see Chapter VI, APPENDIX 10 and APPENDIX 17, clause 7.3.28). ...

And here we come close to what can be called “The Riddle from N.M. Przhevalsky”, and first we will consider its formulation in full, at least that part of it that concerns the history of the early stage of shipping on the Amur (in the life of N.M. Przhevalsky generally has many mysteries, which we will not mention, since they do not relate to our topic).

The famous Russian traveler, colonel of the General Staff of the Russian Military Department, who served in the military topographical department (that is, a professional intelligence officer in the field of economic-statistical and natural-geographical description of countries adjacent to Russia), N.M. Przhevalsky, after his trip to Dalniy Vostok in 1867-69, published a book in 1870 describing the “legal” part of his trip entitled “Travel in the Ussuri Territory”, where, in particular, he briefly but concentratedly indicated the quantitative state of the shipping company on the Amur during this period, not citing, however, the exact year of his reports(but he himself, according to the materials of the same book, began sailing in the Amur basin on June 9, 1867, boarding a steamship he did not indicate on Shilka in Sretensk).

And, thereby leaving a “mystery” for future historians, he set a TASK, the exact statement of which we will quote in full below: “In general, all water communications along the Amur are carried out by 12 state-owned and 5 private steamships; in addition, there are 4 more steamships here Telegraph and 3 Engineering Departments, so that there are a total of 24 steam ships,... including 2 state-owned steamships on the Ussuri River and Lake Khanka" [Przhevalsky N.M. Travel in the Uss. region. 1867-1869. - St. Petersburg, 1870, pp. 5-6; the same (reprint): M., 1937, pp. 12-13].

And this is practically all about shipping on the Amur. Przhevalsky, having published his information in the form of a brief quantitative “formula” (12+5+4+3 = 24 ships), did not indicate a single ship by name, nor the exact year of his report, nor the source of information.

Subsequently, this “summary” by N.M. Przhevalsky, arbitrarily linking it in time to 1867 (or approximately to the end of the 1860s), was referred to by almost all those historical authors who described the state of navigation on the Amur in the initial period, who completely “formula” - 12+5+4+3=24, for example, the first were Alyabyev in 1872 [Alyabyev, p.6] and F.F. Shperk in his work of 1885 [Shperk, 1885, p.484]; then, with various options for summing - either semi-generally (12 + 5 + 7), or generalized (19 “official”, 5 private), or “totalitarian” (“total - 24”) - many other authors of the pre-revolutionary period - prof. . V.E. Timov [Timonov, 1897, p. 204], engineer R. O. Yurgenson [Yurgenson, 1897, p. 82], V. I. Kovalevsky and P. P. Semenov, authors of the collection “Siberia and the Great Siberian Railway" [Siberia and.., 1893, p. 268; 1896, p.244], A.I.Dmitriev-Mamonov [Guide to.../Dmitriev-Mamonov, 1900, p.446], A.Lubentsov [Lubentsov//Priam.ved. (Hab.), 1901, No. 395 (July 22)] and many others, including a compilation, but still cited by A.V. Dattan [Dattan, 1897, p. 17] with the formula (12+7+5), as well as from the Soviet period - B. Shcherban [Shcherban, 1954], F.F. Kovalev [Kovalev, 1973] and others, mostly not historians, but “retired watermen”, veterans of the Amur River Shipping Company.

But none of these authors made an attempt to establish, in one way or another, exactly which steamships N.M. had in mind. Przhevalsky did not try to solve his “riddle”, decipher his “formula” and, having checked it, also establish its relatively exact date. There are two possible ways to solve this problem: it is possible that somewhere in Przhevalsky’s papers, in his diaries and working drafts of the book, this information was preserved, but we did not search for his archive, trying to follow the second, deductive-paleontological path - in To restore all components of Przhevalsky’s quantitative summary based on the primary sources of that period, independently of him. That is, try to compile YOUR list of Amur steamships from the beginning of steam navigation on it until the time of the author’s journey in 1867, with all the changes in time, and also extending it a little further, until the milestone year on the Amur in 1872, when dramatic changes took place in the Amur basin , associated with the liquidation of the river part of the Siberian Flotilla of the Maritime Department and the formation of the private, but subsidized by the state, "Partnership of Express Shipping Company on the Rivers of the Amur Basin", abbreviated as "Partnership of the Amur Shipping Company" with the constant abbreviation "TAP", "Highly established" on September 15, 1871 by the Emperor Alexander II [PSZ, 1871, vol. XLVI, - St. Petersburg, 1874, No. 49971] and began its operations with the navigation of 1872, and TAP included many early Amur steamships, listed “unnamed” in N.M.’s report. Przhevalsky.

With this “deductive” approach, many unexpected points arose: firstly, by the approximate date of his summary (1867), many of the first “state-owned” steamships had already retired (mostly, they were dismantled or turned into barges); secondly, some ships were initially private, and only then were transferred “to the treasury”, and some were taken away from the basin, so their number (both in general and by type of owner) varied from year to year, which, as it turned out, forces us to clarify the date (year) of Przhevalsky’s summary, considering his very “formula” (12+5+4+3) immutable; thirdly, the same “formula” clearly excludes all steam boats (some of which were no smaller in size than the small steamers included in it); so in total, in the minimum period under consideration - up to 1867 inclusive (not touching in this case 1872) - not 24, but over 30 steam ships were launched into the waters of the Amur, the history of each of which must be considered equally. ...

Among the first steamships implied in the quantitative summary of N.M. Przhevalsky, there was also a small tug-passenger steamer, better known under its second name - “Cossack Ussuriysky”, with a long further service life, but which practically remained unknown under many of its subsequent ones (“white " and Soviet) names, since it is almost not mentioned with them in publications about shipping on the Amur after 1917. ... or, on the contrary, considering the YEAR of the report immutable, propose your own “formula”, with the same total number of ships themselves - 24, but with a slightly different distribution among departments (see Chapter XI).

Chapter 12 Amur flotillas 1857–1917

As you know, Russian explorers first appeared on the Amur in the middle of the 17th century. These were separate detachments of Cossacks who collected tribute to the treasury. And only in the middle of the 19th century. economic life in Far Russia significantly revived thanks to the energetic activities of the Governor-General of Eastern Siberia N. N. Muravyov-Amursky. In 1849–1855 The Amur expedition under the command of Captain 1st Rank G.I. Nevelsky (several officers and 60 sailors) began hydrographic descriptions of the river.

The spring of 1852 was marked by the beginning of steam navigation in the waters of Far Russia. The Argun steamship, built at the Shilkinsky plant, sailed to the Amur. On May 14, N.N. Muravyov-Amursky set out from Nerchinsk on 77 ships on his first military expedition. A month later, the caravan safely arrived at the Mariinsky post, not far from which a hundred cavalry Cossacks of the Transbaikal army founded the village of Suchi. The ships of the caravan also brought the necessary tools, materials, ammunition and food for two years.

In the spring of 1854, the second raft also transported a hundred horsemen with the necessary two-year supplies. The commander of the detachment, Yesaul Skobeltsyn, was supposed to examine the mouth of the Burey River in order to select a place for new settlements of a six-hundred-strong cavalry regiment and four foot Cossack battalions.

In the spring of 1857, the resettlement of the Cossacks became more intense, as the steamships of the Siberian flotilla “Amur” and “Lena” were assembled and launched in Nikolaevsk-on-Amur. By the end of the year, 17 villages were founded on the Amur, which housed 3 cavalry hundreds and two army battalions with a field artillery division. The number of Cossacks amounted to 1850 souls of both sexes. During the next 1858, the number of settlers amounted to 2,350 souls, and the number of villages - 32. The cavalry regiment was fully formed and the resettlement of foot Cossacks began, who founded, by the way, the village of Khabarovka (now Khabarovsk).

From 1857 to 1863 The flotilla of state-owned steamships and barges on the Amur River reached significant sizes and was mainly engaged in economic transportation to supply military posts and Cossack villages with everything necessary. The backbone of the flotilla consisted of steamships of the War Department, some of them could be armed with artillery. The personnel of all departmental ships was staffed by sailors of the Amur naval crew (Table 1).

In 1878, to strengthen the defense of the mouth of the Amur River, torpedo boats were transported by rail to Nikolaevsk-on-Amur, which became part of the Siberian flotilla (Table 2).

In 1885, the commander of the troops of the Amur Military District first raised the question of creating the Amur River Flotilla. For economic reasons, the decision did not take place, but in 1897 the small Amur-Ussuri Cossack flotilla began to operate. However, burdened with servicing the villages, the two steamships of this flotilla could only in exceptional cases help protect the borders and fight Honghuz gangs. Therefore, in 1898–1900. The issue of creating a powerful river flotilla was considered in an interdepartmental commission that worked on the initiative of the War Ministry. The Amur River, due to its enormous length, before the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway, was the only route of communication between Nikolaevsk, Khabarovsk and Blagoveshchensk - in the summer by ships, in the winter by sleighs. By the end of the century, 46 years after the start of steam navigation, 160 steam ships and 261 barges were already sailing on the waters of the Amur Basin. In addition, 1 steamship, 15 sailing ships and 20 barges sailed along the Selenga. This significance of the Amur River came into sharp relief in 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion, when the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) was under construction and materials were delivered by rafting along the rivers. In addition, to pacify the uprising of the Boxer and Honghuz gangs, troops with military supplies had to be transported on commercial ships and barges, on which temporary protection was provided from bags of earth and sand.

The steamships of the Amur-Ussuri Cossack Flotilla and the Ministry of Railways: “Selenga”, “Sungari”, “Gazimur”, “Amazor”, “Khulok” and others were armed with light artillery and machine guns. The commander of the Vladivostok port allocated for this purpose ten 4-pound guns of the 1867 model, three 47 mm and one 37 mm five-barrel Hotchkiss gun. Hastily armed steamships were of great use as reconnaissance, escort and patrol vessels.

Table 1 Flotilla of state-owned steamships on the river. Cupid 1857–1867

| Class and name | Length, m | Width, m | Draft, m | Displacement, t | Machine power, hp | Number of guns | Construction plant | Descent time | Note |

| Steamships of the War Department | |||||||||

| "Zeya" | 38,40 | 4,88 | 0,31 | - | 40 | - | Beit & Co. Hamburg | 07/10/1860 | Swimming district - r. Shilka, travel speed 15–16 versts per hour |

| "Onon" | 38,40 | 4,4 | 0,38 | 140 | 30 | - | Beit & Co. Hamburg | 07/21/1860 | |

| "Ingado" | 38,40 | 4,4 | 0,38 | - | 30 | - | Beit & Co. Homburg | 08/03/1860 | P-on swimming - r. Shilka, travel speed 13 versts per hour |

| "Chita" | 36,62 | 3,81 | 0,61 | - | 40 | - | Beit & Co. Hamburg | 08/13/1860 | P-on swimming - r. Shilka, travel speed 16–17 versts per hour |

| "Konstantin" | 45,72 | 8,23 | 0,61 | - | 100 | - | Cockerill Island | 05/17/1864 | P-on swimming - r. Amur |

| "General Korsakov" | 39,62 | 7,62 | 0,96 | - | 70 | - | London | 1860 | Acquired from the Amur Company in 1863, navigation area - r. Amur |