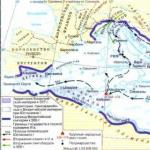

On the twenty-fifth day of the eighth month in the twenty-second year of his reign, Pharaoh Thutmose III passed the fortress of Charu (Sile), located on the eastern border of Egypt, “to repel those who attacked the borders of Egypt” and exterminate those who were “inclined to rebel against his majesty " In Central and Northern Palestine, a union of three hundred and thirty local princes was formed, the soul of which was the Hyksos, expelled from Avaris and Sharukhen. At his disposal was the king of Kadesh, who decided to resist by force of arms any attempts by Egypt to establish its dominance in Syria. It seems that only Southern Palestine remained loyal to the pharaoh. After the preparations were completed, Thutmose set out on a campaign along the great military road, which then, as now, starting at Kantara (in the area of the modern Suez Canal), ran along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. On the fourth day of the ninth month in the twenty-third year of his reign, on the anniversary of his accession to the throne, the pharaoh arrived in Gaza. The passage continued through Ashkelon, Ashdod and Jamnia, where the Egyptian army apparently abandoned the desert road linking Jamnia to Jaffa to follow the caravan route inland along the foothills and through the Carmel mountain range. Eleven days after Thutmose left Gaza, he reached the city of Ichem at the foot of the mountain. There he was informed that the enemies were located on the other side, in the Ezraelon Valley, and had chosen the fortified city of Megiddo as the center of their defense.

It was necessary to cross the mountains and engage the enemies near Megiddo. The only thing that was in doubt was the path that should be taken. There were three possibilities in total. The first and closest route led from Ichem through Aruna directly to Megiddo, passing through a narrow gorge where the army could advance slowly, “horse by horse and man by man.” In addition, there was a very real danger that the enemies could engage the vanguard of the Egyptian army as soon as it emerged from the gorge into the open, and easily destroy it before the rest of the army could arrive with reinforcements. The other two paths were longer but safer.

The king convened a military council to come up with a decision on the correct route for the campaign. Everyone believed that the nearest, but most dangerous path should be abandoned in favor of one of the other two. However, Thutmose took this advice as a manifestation of cowardice and expressed the opinion that the enemies would also attribute to fear the choice of any other than the direct path to the battlefield. In front of his army, the pharaoh exclaimed: “Because Ra loves me, and my father Amon praises me, I will go along this road to Aruna; let those of you who [desire] follow those other paths that you have named, and let those of you who [desire] follow my majesty.” So the most difficult and dangerous road was chosen. The army set out on a campaign and reached Aruna three days later. After a night halt at the top, early in the morning it descended into the Ezdrelon Valley. The king personally set out with the vanguard of his army and, walking slowly through a narrow gorge, had already descended into the valley while the bulk of his army was still in the mountains and the rearguard had not even left Aruna. And yet the terrible enemy attack did not occur. They positioned themselves in battle formation in front of the gates of Megiddo and, for some unknown reason, made no attempt to hinder the advance of the Egyptians. Accordingly, Thutmose was able to lead his army into the valley without interference and settle into a fortified camp. The soldiers rested for the night and gained strength to meet the enemies the next day. The battle began at dawn. The pharaoh climbed into his “golden chariot, adorned with his military armor, like Horus, mighty in hand, and the Theban Montu” and took his place at the head of the army. The enemies wavered before the fierce attack of the Egyptians and rushed to run to the city walls. They discovered that the inhabitants had already closed the gates, and so the fugitives, including the ruler of Kadesh, who was at the head of the rebellion, and the ruler of Megiddo himself, had to be dragged over the wall using their clothes as ropes. The losses of the enemies, thanks to their rapid flight, were very small, only eighty-three people died, whose hands were cut off and folded before the Pharaoh, and three hundred and forty were captured. However, the entire Allied camp was in Egyptian hands, including a huge number of war chariots and horses abandoned by their owners. The Egyptian soldiers were so greedy about the rich booty that they completely missed the opportunity to pursue the enemy and capture the city. Pharaoh's reproaches were useless: they came too late. So he was forced to besiege Megiddo, “the capture of which was the capture of a thousand cities,” and, through a blockade that lasted seven months, starve it into submission. Ditches were dug and ramparts were erected around the city to prevent any attempt to make a sortie. Of course, final capitulation was inevitable. The rulers personally left the city and fell at the feet of Pharaoh to “ask for breath for their nostrils.”

“Then this fallen one [the lord of Kadesh], together with the princes who were with him, caused all their children to come out to my majesty with many objects of gold and silver, all their horses with their harness, their great chariots of gold and silver with their painted parts, all their battle armor, their bows, their arrows and all their weapons - undoubtedly those things with which they came to fight against my Majesty. And now they brought them as tribute to my majesty, while they stood on their walls, glorifying my majesty, that the breath of life might be given to them.

Then my Majesty made them take an oath and say: “Never again in our lives will we do harm against Menkheperre [throne name of Thutmose III] - may he live forever - our master, for we have seen his strength. Let him only give us breath according to his desire...”

Then my Majesty granted them the way to their cities, and they departed, all of them, on donkeys. For I took their horses, and I took their inhabitants to Egypt, and also their property.”

So, the booty captured during the first attack under the walls of the city increased many times after the siege. 2041 horses, 191 foals, 924 chariots were obtained, 892 of which were of ordinary quality, while the rest were richly decorated with gold and silver, as described above, as well as a variety of useful weapons. The royal palace at Megiddo was sacked, the loot including not only 87 children of the ruler himself and allied lords, but also 1,796 men and women of lower rank, as well as others, and a large quantity of expensive household utensils, including jugs of gold and other vessels, objects furniture, statues and other things too numerous to mention. Among the animals that fell into the hands of the Egyptians, in addition to the horses already mentioned, were 1,929 oxen, 2,000 head of small livestock, and 20,500 other animals. Moreover, all the crops in the fields around the city were collected by the besiegers, and, in order to prevent their theft by individual soldiers, were carefully measured and transported by sea to Egypt.

With the capture of Megiddo, the pharaoh again defeated all of Northern Palestine with one blow, the remaining rulers of Syria hastened to express their loyalty by sending gifts to the conqueror. Even the king of Assyria sent his share of the “tribute” from his distant residence on the Tigris, consisting of large pieces of lapis lazuli and several expensive Assyrian vessels. The defeated rulers were forced to hand over hostages, who were sent to Egypt, and there is no doubt that many of the daughters of the Syrian kings were sent to the Pharaoh's harem. As an eternal reminder of this great victory, Thutmose ordered three lists of conquered cities to be carved in the great temple at Karnak. Each of them is represented by an oval in which its name is written in hieroglyphs, and is crowned with the bust of a man with his hands tied behind his back. This man, with his large hooked nose, prominent cheekbones and pointed beard, was clearly the epitome of a Syrian. In one of the accompanying scenes, the pharaoh is depicted as the conqueror of Asia wearing the crown of Lower Egypt, holding by the hair of several kneeling Asians whom he beats with a mace, while the goddess Thebes approaches him from the right, leading various captured Syrian cities bound with rope to present their king.

Despite the great victory that Thutmose III won in the battle before the gates of Megiddo in the Ezraelon Valley, his ultimate goal was the conquest of Syria as far as the banks of the Euphrates in the middle reaches and the Taurus and Amanos mountains, where the rich and powerful trading cities put up stiff resistance to maintain their freedom , - was not achieved. Warjet, which was defended by an army from neighboring Tunip, was captured, and Ardata was sacked and destroyed. Here, Egyptian soldiers feasted in rich houses and drank in the wine cellars of local residents. They got drunk every day and were “anointed with oil, as at the feasts in Egypt.” To leave the city in complete submission and powerlessness, the king ordered the destruction of all crops, vineyards and fruit trees in the surrounding area, thus putting an end to the main source of income for the population. While the pharaoh's army was returning to Egypt by land, two captured ships were transporting the booty captured during the campaign. However, Ardata, despite all the punishments, was not crushed. Therefore, the pharaoh considered it necessary the next year - the thirtieth year of his reign - to again go on a campaign against the rebellious city, which he captured and plundered for the second time. The population, more affected than before, decided to recognize the authority of the Egyptian king and regularly pay the required tribute. The fate of Ardata was shared by Simira and Kadesh.

On the coast of Palestine a little further south, the port city of Joppa - modern Jaffa - also appears to have surrendered to the Egyptians without resistance. It was besieged and, according to later Egyptian legend, eventually captured only through stratagem. When the Egyptian general Djehuti was encamped outside the walls of Jaffa, he devised some means to induce the ruler of the city to visit him.

Having accepted the invitation, the prince, accompanied by a detachment of soldiers, appeared in the foreigners’ camp. They were well treated, their horses were well fed, and after a while the guests lay drunk on the ground. Meanwhile, the ruler of Jaffa sat and talked with the military leader Djehuti. Finally, he expressed a desire to see “the great war mace of King Thutmose III,” which Djehuti had. The latter ordered it to be brought, took it by the shaft and unexpectedly struck the “enemy from Jaffa” in the temple, who, having lost consciousness, fell to the floor and was quickly tied with a rope. After the leader of the enemy was eliminated in this way, two hundred baskets were brought, and two hundred Egyptian soldiers with ropes and wooden blocks hid in them. Djehuti then sent a letter to the charioteer of the Prince of Jaffa, who was probably waiting outside, knowing nothing of what had happened to his countrymen and his master, telling him to return to the city to announce to the wife of the Prince of Jaffa that her husband had captured the general of the Egyptians and was coming home with the loot. Of course, the long procession was indeed approaching the city: baskets laden with “loot” and accompanied by five hundred “captives” passed through the city gates. As soon as they were all inside, the “prisoners” released their comrades from the baskets and instantly won a victory over the garrison. The fortress was taken. That night, Djehuti sent a message to the Pharaoh in Egypt, reporting his success: “Rejoice! Your good father Amon gave you the enemy of Jaffa, all his people and his city. Send men to take them away as captives, so that you can fill the house of your father Amon-Ra, the king of the gods, with male and female slaves, who will be laid under your feet forever and ever.” Whatever the legendary details of this story - the Egyptian version of the story of the Trojan Horse - there can be little doubt about the authenticity of the main part concerning the capture of Jaffa by means of cunning. The hero Djehuti is a very real historical figure. He bore titles that indicate that he was something of a governor of Syria, who accompanied the king abroad and remained in charge of the conquered territories. Several items survive from his tomb, including two remarkable bowls, a beautiful dagger and several wonderful alabaster oil vessels.

Much stronger was the resistance that Thutmose III had to face in northern Syria, especially from Kadesh, a city on the banks of the Orontes, whose prince led a major revolt against Egypt in the twenty-second year of his reign, and from the distant country of Mitanni. The first attack on Kadesh occurred in the thirtieth year, when the city was captured and sacked, "its groves laid waste and its grain reaped." However, Kadesh quickly recovered from the defeat. The fortifications destroyed by the Egyptians were rebuilt and measures were taken to prevent a new attack. Then Thutmose realized that before starting the new campaigns that he had planned, serious preparation was needed. It was carried out during the seventh campaign, which occurred in the thirty-first year of the king's reign, when he captured Ullaza on the Phoenician coast and established storehouses with many supplies in "every port city" he reached. Two years later he was ready to set out on his largest campaign. Having crossed the Orontes near Homs, the pharaoh captured Qatna. At the next battle of Aleppo, he was joined by the general Amenemheb, who had arrived in Southern Palestine to suppress the uprising in the Negeb. From Aleppo the route lay northeast to Karchemish, which quickly surrendered. Then, using boats built from coniferous trees (“cedars”) in the mountains beyond Byblos and transported to the Euphrates on oxen-drawn carts, Thutmose ferried his army across the great river for his ultimate goal - the conquest of Naharina. Another great victory was won, but the king of Mitanni withdrew most of his soldiers to one of the distant provinces, leaving only 636 captives for the Egyptians. Thutmose completely devastated the unfortunate state of Mitanni, and then, having erected his victory stele on the eastern bank next to his father's stele, crossed the Euphrates again and turned southeast, winning several more victories on the way home. Sinjar was taken, and finally, three years after the first capture, Thutmose again lined up his horses and chariots under the walls of Kadesh. Still stung by the memory of his previous defeat, the ruler of the city came up with an original military stratagem. He released in front of the formation of Egyptian war chariots, each of which was harnessed to a pair of stallions and a mare. The horses immediately became restless, the entire rank trembled and were ready to mix up the battle formation. At this tense moment, the valiant Amenemheb jumped from his chariot and rushed forward to stop the galloping mare. With a deft blow of his sword, he “cut her belly, cut off her tail and threw it before the king,” while the army expressed its admiration with noisy cries. The ruse failed, but the ruler of Kadesh remained safe inside his restored fortress, not thinking about surrender. Thutmose ordered the brave Amenemheb to conquer the city. The warlord, with a few select troops, succeeded in attempting to make a breach in the wall. In his tomb preserved in Thebes, he writes that he was the first Egyptian to penetrate the wall of Kadesh. So, the attackers broke into the city and occupied the citadel. Rich booty fell into their hands. After other successes in the Takhsi region near Kadesh, Thutmose turned north again and led his troops to Niya, where he erected another commemorative stele.

When the pharaoh and his army were in this area, he was informed about a herd of elephants that were feeding and basking in the mountain lakes of Niya. To take a break from the military routine, a big hunt was organized, and the king encountered a herd of one hundred and twenty animals. During this hunt, a misfortune almost happened to Thutmose. One enraged animal attacked him and would undoubtedly have killed him if the brave Amenemheb had not rushed to the aid of the pharaoh and cut off the elephant’s trunk with a sword, “standing in the water between two rocks.”

This victorious campaign made a deep impression on the people of Northern Syria. Many gifts were sent to the pharaoh from all sides, including rich offerings from Babylonia and the country of the Hittites, huge quantities of which were transported to Egypt as tribute on ships specially built for this purpose in one of the captured ports of Lebanon.

While Thutmose III waged wars in Western Asia for several decades and pushed Egypt's northern border back to the Euphrates, his annals show that he only needed two expeditions up the Nile to establish the southern border at Napata. He built a small temple at Gebel Barkal and, in the forty-seventh year of his reign, erected a huge stele of gray granite in it to impress his Nubian subjects with all the valor and strength of their Egyptian overlord. Three years later, the king cleared a canal blocked by stones in the area of the first cataract and ordered that local fishermen constantly take care of it. On the seventh pylon of the Temple of Karnak, as an analogue to the lists of Palestinian cities that he conquered during the campaign against Megiddo, Thutmose compiled a similar “list of the southern countries and Nubian peoples that his majesty conquered.”

However, most of them came under Egyptian rule even earlier, and some never belonged to the Egyptian Empire. However, even if this list, like the others, is not to be fully trusted, there can be no doubt that Thutmose III did in fact extend his power over the powerful empire "as his father Amon had commanded him." In the name of the Theban king of the gods, the pharaoh went to war, under his protection he killed despised enemies, and, finally, the lion's share of the booty that was brought to Egypt from the conquered lands was intended for his temple.

To express the deep gratitude that the king had for Amun (see plate 12), the priests of Karnak composed a wonderful victory poem in which the returning king was welcomed and praised by his divine protector.

Come to me, rejoicing that you see my beauty, O my son, my protector, Thutmose...

I gave you courage and victory over all countries;

I have placed your power and fear of you in all lands,

And the horror before you reaches the four pillars of the sky...

The rulers of all countries are clamped in your hand -

I stretch out my hands to bind them for you;

I bind Nubian nomads by the tens of thousands and thousands,

And the northern peoples are hundreds of thousands.

I throw your enemies under your sandals, and you destroy the disobedient,

For I gave you the land from end to end,

Westerners and Easterners are under your rule.

You trample all foreign lands with a joyful heart,

and no one dares to approach you;

Because I'm your counselor and you're overtaking them.

You crossed the waters of the Great Bend of Naharina in the victory and power that I gave you.

They hear your battle cry and crawl into their holes;

I deprived their nostrils of the breath of life; I allowed horror before Your Majesty to fill their hearts.

Uraeus on your head, he burns them; he destroys with his flame the inhabitants of distant plains;

He cuts off the heads of the Asians, and none of them escape.

I give that your victories will penetrate into all countries;

What my uraeus illuminates is subordinate to you.

No one rises up against you under heaven;

They come with gifts on their backs, bowing to your majesty, as I commanded.

I give fall to every attacker that comes close to you:

Their hearts are burning and their bodies are trembling.

I have come to let you defeat the rulers of Jaha;

I scattered them under your feet in their lands.

I let them see your majesty as the lord of the rays: you

you shine before them in my form.

I have come to let you overthrow the inhabitants of Asia;

And you smash the heads of the Asians Rechenu.

I let them see your Majesty dressed in your armor,

When you take a weapon in a war chariot.

I have come to let you overthrow the East;

And you trample on the inhabitants of God's Country.

I let them see your majesty like a comet,

That spreads its flame and spreads its tail.

I have come to let you overthrow the West;

Keftiu and isi are subject to your authority.

I let them see your majesty as a young bull,

Strong in heart and sharp in horns, completely unattainable.

I have come to let you overthrow those who live on

their distant plains:

The lands of Mitanni tremble in fear of you.

I let them see your majesty as a crocodile,

The Lord of Terror is in the water, no one comes close to him.

I have come to let you overthrow the people of the islands;

Those who live in the middle of the sea bow to yours

battle cry.

I let them see your Majesty as an Avenger,

Crowned in glory on the back of his victim.

I have come to let you defeat the Libyans;

The Uchentiu yielded to your might.

I let them see your majesty as a furious lion:

You turn them into corpses in their valleys.

I have come to let you overthrow the limits of the world;

That which surrounds the sea is grasped in your hand.

I let them see your majesty as a soaring falcon,

Who grabs what he sees according to his desire.

I have come to let you overthrow those who live in the upper part of the world;

You take the inhabitants of the sands captive.

I let them see your majesty as the jackal of the Upper

Egypt, fleet-footed,

A runner who scours the Two Lands.

I have come to let you defeat the Nubians;

Everything is in your hand until Shatiu-jeb.

I let them see your majesty as your two brothers [Horus and Set],

Whose hands have I joined with your [hand] in victory.

This song of praise, which was a model of form and style and whose structure is easily discernible even in translation, became extremely popular and was later often copied and used to glorify other pharaohs.

In the thirtieth year of his reign, Thutmose was able to celebrate for the first time his thirtieth anniversary from the day he was named heir to the throne. Since it had been the custom since ancient times to repeat this jubilee every three or four years after the first celebration, during the remaining twenty-three years that were allotted to him by fate, he enjoyed a number of these celebrations that was very unusual for an Eastern ruler. According to ancient tradition, the celebration of these anniversaries, heb-sedov, was marked by the erection of obelisks. Four of these wonderful monuments of Thutmose III have come down to us: two that were once erected at Thebes, and a pair that were originally installed in front of the temple of Ra at Heliopolis. By a surprising irony of fate, not one of them remained in its ancient place. Some of them dates back to ancient times, while others in modern times were transported to completely different places. One of the Theban obelisks, by order of Emperor Constantine the Great, was sent to Byzantium, the eastern capital of the Roman Empire, which was renamed Constantinople in his honor. Emperor Theodosius ordered it to be installed at the Hippodrome, where it is still located, but this did not happen earlier than 390. The second Theban obelisk, 32 meters high, to which Thutmose IV added the inscription during his reign, was taken to Rome and installed in the Circus Maximus around 363. However, for some reason it fell and lay under heaps of ruins for centuries, until Pope Paul V dug it up in 1588 and installed it on a new foundation in front of the grandiose building of the Basilica of St. John on the Lateran Hill. Even more remarkable are the wanderings of the two Heliopolis obelisks. By order of Prefect Barbara, in the eighth year of the reign of Augustus in Egypt (23 BC), they were delivered to the Egyptian capital, Alexandria, so that they could be installed in front of the Caesareum in the new suburb of Nicopolis. These obelisks are the famous “Cleopatra’s needles,” as the Arabs named them in honor of the great queen. However, they were both destined for further wanderings. Subsequently, one of them, about 21 meters high, which lay on the ground for more than a thousand years, was donated to the British government by Muhammad Ali and, at the expense of a private individual, a resident of London, was taken away in 1877 for installation on the Thames embankment, where it is still located, almost destroyed by smog and soot. The second Heliopolis obelisk was brought to New York in 1880 as a gift to the United States government from the Egyptians. It has now become one of the most famous landmarks in Central Park. So, in four modern cities of the Old and New Worlds, these four colossal red granite obelisks extol the glory of the ancient “conqueror of the world” Thutmose III and fulfill the wish of the greatest of the pharaohs that “his name could remain in the future forever and ever”, much better than he expected.

If, according to the Egyptian point of view, the virtue of a ruler is mainly manifested in his service to the gods and in the temples he builds for them, then Thutmose III is without a doubt one of the best pharaohs. From the spoils obtained during his wars, he made rich gifts to various priesthoods, and in Egypt there is hardly at least one large city where there are no traces of his active construction. Unfortunately, few temples that owe their existence to him have survived to this day, with the exception of those that the pharaoh built in Thebes (we will return to them later).

Almost at the very end of his reign, Thutmose III appointed his only son Amenhotep, who was born by his second wife, the “great royal wife” Hatshepsut-Meritra, as co-ruler. However, father and son did not share the throne for long, for on the last day of the seventh month of the fifty-fourth year of his reign, Thutmose III “ended his time; he flew up into the sky, united with the sun and merged with the one who created him.” He was about sixty-five. Even in the fiftieth year of his reign, he conducted his last campaign in Nubia, and shortly before his death, together with his son and co-ruler Amenhotep, he participated in a review of the army.

Thutmose III built himself a large rock tomb as his final resting place in the secluded Valley of the Kings, where his father was buried and Hatshepsut carved his own tomb. It begins with a sloping corridor over 19.8 meters long, which leads from the entrance to a huge shaft with sides approximately 3.7 by 4.6 meters and a depth of 4.6 to 6 meters. On the other side of the shaft there is a huge hall with two square columns, the walls of which are decorated with no less than 741 images of Egyptian deities. In the far corner of this hall in the floor is the entrance to the second corridor, which is a staircase with low steps and descends into the main hall of the tomb. The ceiling of this room is also supported by two rectangular columns. Its walls are covered with images and hieroglyphic inscriptions, all painted on a yellowish-gray background in black and red paint in an “italic” style. As a result, it seems as if the walls of the entire chamber are covered with huge papyrus. The viewer discovers here, unfolded before his eyes and intact, a copy of one of the most famous and most valuable books of his time - “The Book of the Underworld.” It is a kind of guidebook, the knowledge of which was necessary for the king if he wanted to successfully make a night journey through the underworld with the solar god Ra. In this room, on an alabaster base, stood a sarcophagus made of yellow quartzite, which once contained a wooden coffin with the king’s mummy. However, Thutmose III, like some of his ancestors, was not destined to rest forever in the place he chose. About five hundred years after his death, persistent robbers entered his underground burial chambers, who not only opened the stone sarcophagus and robbed the mummy, but also tore the body into three parts. It was found in this state by the guards of the necropolis, who again carefully wrapped it in the original bandages and fabrics and transported it to the “royal hiding place”, where it was discovered along with other royal mummies in 1881. Currently, the coffin and mummy of the king are kept in Cairo.

There is no doubt that Thutmose III was one of the most significant personalities who ever occupied the throne of the pharaohs. If any Egyptian ruler deserves the honor of being called “The Great,” Thutmose is a more suitable candidate than all others, and certainly more than the later Ramesses II, to whom this epithet has been unfairly assigned by some modern historians of ancient Egypt. The Egyptians were fully aware of his greatness and “how much the gods loved him.” For centuries, his throne name, Menkheperra, was considered a powerful spell for good luck and was written on countless amulets to protect their owners from misfortune. The deeds of the king who founded the Egyptian world empire were preserved in the memory of the people and were embellished with many legendary details. Only his name was forgotten. When the nephew of the Roman emperor Tiberius Germanicus in 19 AD. e. visited Thebes and wandered through the vast territory of Karnak, he persuaded one of the priests to explain what was written in the long inscriptions on the walls, which to this day have preserved almost the only record of the military exploits of Thutmose III. The helpful priest, accordingly, told him how the king with an army of seven hundred thousand defeated Libya and Ethiopia, the Medes and Persians, the Bactrians and Scythians, Cappadocia, Bithynia and Lycia, that is, almost all of Asia Minor. He also read what tribute was imposed on all these peoples, about the measures of gold and silver, the multitude of chariots and horses, ivory, grain and all other items that each of these peoples had to supply - everything that the annals of Thutmose III actually describe . However, when the priest was asked who achieved all this glory, he named not Thutmose III, but Ramesses - the same Ramesses whom the modern dragoman is still accustomed to calling every time he tells an open-mouthed tourist about the amazing wonders of the ancient monument.

Pharaoh Thutmose III. Around 1460 BC.

The image is reprinted from the site

http://slovari.yandex.ru/

Commander

Thutmose III (reigned ca. 1525-1473 BC), Egyptian pharaoh, commander. From 1503 he waged wars of conquest; During his reign he made a number of campaigns, ch. way to Palestine and Syria. In history he is known as the first commander to carry out an offensive according to a pre-planned plan. A characteristic feature of his military approach was the desire not to scatter his forces, but to deliver consistent and concentrated attacks on the most important strategic points. Having quite a large number of (up to 20 thousand people) and a well-organized army, Thutmose III in 1492-1491 BC. defeated Mitanni (an ancient state in Northern Mesopotamia) and captured its lands 3. from the Euphrates, won victories at Megiddo, Kadet, Carchemish, etc. (see Ancient Egypt). As a result of the victorious campaigns of T. III, Egypt expanded its borders and became the largest state. Libya, Assyria, Babylonia, the Hittite Kingdom and Fr. became dependent on Egypt. Crete, who paid him tribute.

Materials from the Soviet Military Encyclopedia were used. Volume 8: Tashkent – Rifle cell. M. 1980.

Egyptian pharaoh

Thutmes III - son of Thutmes II, sixth pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (1525-1491 BC). For twenty-two years he was co-ruler of his stepmother Hatshepsut, but had no real power. Having become the sole ruler of Egypt in 1503, Thutmes III destroyed the memory of Hatshepsut. With his accession to the throne, a short period of peace ended and the era of great conquests began.

Thutmes III made his first trip to Western Asia. The reason for this campaign was the uprising of Syrian cities, which formed a coalition hostile to Egypt, led by the ruler of the city of Kadesh. The Syrians concentrated their forces near the city of Megiddo. In order to surprise them, Thutmes III moved to Megiddo by the shortest, but most difficult route, which lay through a difficult mountain pass. The Egyptian chronicle says: “And he himself went ahead of his army, showing the way to every man. And horse followed horse, and His Majesty was at the head of his army.” Having crossed the pass, the Egyptians found themselves close to the enemy camp. The next morning a bloody battle began. The pharaoh personally led the army into the attack, driving a war chariot. The Syrians were unable to provide adequate resistance and fled. Instead of pursuing the fleeing enemy until complete destruction, the Egyptians began to plunder the enemy camp and collect weapons abandoned on the battlefield. This allowed the Syrians to take refuge in Megiddo. It was not possible to take the city by storm, since the Egyptians in those days did not know how to storm fortresses; a long siege began. For seven months the army of Thutmes III stood at the walls of Megiddo. Finally, exhausted by hunger and thirst, the city surrendered. Thutmes III received huge booty, which he sent to Egypt, and he himself moved further to the north. His army reached the southern slopes of the Lebanese Mountains, capturing several cities and many villages along the way. To gain a foothold in the occupied territory, Thutmes III left strong garrisons in the cities and erected a fortress, which he gave the name “Thutmes Binding Foreigners.”

Subsequently, Thutmes III annually led an army to Syria. He captured a number of large cities, including Kadesh, Halpu and Carchemish. He also managed to conquer a significant part of Phenicia and thus gain a foothold on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. In the city of Byblos, by order of the pharaoh, a large fleet was built. The ships were transported to the Euphrates on large ox-carts, and Thutmes III and his army sailed down the river. Having reached the borders of Mitanni, the Egyptians began to capture and destroy Mitanni cities and villages. The Mitanians tried to resist, but were defeated in several battles and retreated far beyond the Euphrates.

Thutmes III also fought in the southern direction, in Nubia. He advanced to the fourth cataract of the Nile. As a result of his campaigns of conquest, Egypt became a powerful world power, stretching from north to south for 3,500 km. Enormous wealth flowed into Egypt. Thutmes III generously distributed military awards, lands and slaves to his warriors. A significant part of the loot ended up in temples, primarily in the temple of Amun-Ra in Thebes, since the warlike pharaoh needed the support of the priesthood.

Thutmes III died in the 54th year of his reign, passing power to his son Amenhotep II.

Book materials used: Tikhanovich Yu.N., Kozlenko A.V. 350 great. Brief biography of the rulers and generals of antiquity. The Ancient East; Ancient Greece; Ancient Rome. Minsk, 2005.

Thutmose III, King of Egypt of the Ancient 18th Dynasty, reigned 1490-1436. BC

Thutmose III, one of the most famous conquering pharaohs in the history of Ancient Egypt, was the natural son of Thutmose II by his concubine Isis. During his father's life, he occupied a very modest position in the state-wide temple of Amun in Thebes. But when the old pharaoh died, Thutmose was elevated to the throne by the priests without any difficulty. However, all real power over the country was immediately concentrated in the hands of his aunt-stepmother, Queen Hatshepsut, who ruled Egypt autocratically for 20 years, leaving her stepson-nephew only nominal rights. The importance of Thutmose in these years was so insignificant that dignitaries did not even come to him with reports. Only the death of Hatshepsut returned Thutmose to his due importance. Having seized supreme power after two decades of forced inaction, he tried to destroy all memory of his stepmother. Hatshepsut's name was erased from her monuments. Thutmose ordered the magnificent obelisks erected by her to be built up with a stone wall. Her magnificent statues in the memorial temple of Deil el-Bahri were overthrown and broken. Even the names of Hatshepsut's associates and associates were erased from many inscriptions. But the main thing was not even this - Thutmose radically changed foreign policy. If his stepmother ruled in peace and tranquility, then he spent his entire reign in difficult wars of conquest. (You can get an idea of the appearance of the greatest of the ancient Egyptian conquerors from his mummy and sculptures. He was a short, stocky man, with a low forehead, a large mouth, full lips, a sharply defined chin and an aquiline nose. He was very strong and passionately loved hunting. Being a soldier to the core, the pharaoh was not, however, completely alien to science and art.)

Already in 1468 BC, Thutmose made his first trip to Palestine. Thanks to the detailed inscription on the wall of the Karnak Temple of Amun, we know about all the vicissitudes of this war. Setting out from the border fortress of Jarou, the Egyptian army reached Gaza ten days later, and then spent another seven days moving through the desert to the town of Ihem. Here Thutmose learned that the Syrian kings, under the leadership of the ruler of Kadesh, had formed a strong coalition against him and that their united army was located not far from the powerful fortress of Megiddo. Pharaoh could have taken three roads to this city. The direct route led through the Carmel mountain range and was a narrow path. The other two routes ran north and south of the mountains, respectively. At the council, the military leaders suggested that Thutmose choose one of the bypass roads, but the pharaoh rejected this prudent advice, fearing to be branded a coward among the enemy. Vowing to take the straight path, he offered his comrades the right to choose - to follow him or take bypass roads. Everyone chose to stay with the king. The crossing of the mountains, as one might expect, turned out to be dangerous - the Egyptian army was stretched out on narrow paths for half a day's journey. With one bold blow, the Syrians could completely defeat him. But they did not dare to do this and freely allowed the Egyptians to enter the plain in front of Megiddo. The next day a decisive battle took place. Moreover, after the first onslaught of the Egyptians, the Syrians fled, abandoning their horses and chariots. Thutmose ordered Megiddo to be surrounded by a wall and began a difficult siege that lasted seven months. Finally, having exhausted all options for defense, the Syrians surrendered. The winners received huge spoils. Pharaoh turned all the townspeople into slaves and ordered them to be driven to Egypt. But he treated the captive kings quite mercifully - he took an oath of allegiance from them and sent them home. Having destroyed the city, the victors returned to Thebes in triumph.

The first campaign was only a prelude to new conquests. To strengthen his power in Syria, Thutmose had to equip more and more expeditions there almost every year. Each of them had a specific purpose. In 1461 BC, the Egyptians took the Uarchet fortress. In 1460 BC, Kadesh was captured for the first time. In 1459 BC, the Phoenician city of Ullaza fell. In 1457 BC, Thutmose approached Karchemish and defeated a strong army of Syrians, whose allies were the Mitannians, on the western bank of the Euphrates. Following this, the Egyptians took possession of the stronghold of Karchemish. To continue the war, the pharaoh needed ships. A large number of them were urgently built from Lebanese cedar in Phenicia and brought to the Euphrates on carts drawn by oxen. However, having crossed to the other side, Thutmose no longer found the Mitannians there - they fled in horror. “Not one of them dared to look back,” wrote Thutmose, “but they ran on, like a herd of steppe game.” Having boarded the army on ships, the pharaoh moved down the river, destroying cities and villages. “I set them on fire, my majesty turned them into ruins,” wrote Thutmose. “I took all their people taken captives, their cattle without number, as well as their things, I took their grain, I tore out their barley, I cut down all their groves, all their fruit trees." On the way back near the city of Niya, west of the Euphrates, Thutmose almost died during a great elephant hunt. In 1455 BC, a new battle took place with the king of Mitanni near the city of Arana. Thutmose personally inspired the warriors. Unable to withstand the onslaught of the Egyptians, the Mitannians wavered and fled to the city, abandoning their horses and chariots. After this, Kadesh remained a stronghold of the dissatisfied in Syria for some time, and was retaken by the Egyptians only in 1448 BC. With the fall of this Syrian stronghold, the power of the Egyptians spread to the entire country.

Throughout the Syrian wars, Nubia remained calm. Only once - in 1440 BC - Thutmose made a trip to the south and imposed tribute on the Ethiopian tribes who lived up to the 4 Nile rapids. By the end of the reign of this pharaoh, Egypt reached the highest power in its history and became for a short time the most significant power of the Ancient World. Rich tribute was paid to Thutmose not only by the conquered Nubians, Libyans and Syrians, but also by the kings of Babylonia, Assyria, the Hittites and the inhabitants of the country of Punt located on the shores of the Red Sea. The huge number of prisoners and taxes flowing in from everywhere allowed Thutmose to launch extensive construction. Majestic temples were built during his reign not only in Egypt, but also far beyond its borders - in Ethiopia, Syria and Palestine.

Materials from the book by K. Ryzhov were used. All the monarchs of the world. The Ancient East. M., "Veche". 2001.

Wars of conquest of Thutmose III

Immediately after the death of Hatshepsut, in the 22nd year of his reign, Thutmose III moved his troops to Palestine and Syria. At Megiddo, in Northern Palestine, his path was blocked by the allied Syrian-Palestinian rulers. The soul of the union was the ruler of the Syrian city of Kadesh (Kinza). Contrary to the entreaties of his companions to take a roundabout route, Thutmose, fearing to be branded a coward among his enemies, went to Megiddo straight through a gorge so narrow that soldiers and horses had to follow it in single file. The enemy, standing opposite the exit from the gorge, did not dare to attack the Egyptians when they came out onto the plain one after another. Perhaps the allies were afraid to leave their location near the city. The pharaoh also did not intend to launch a surprise attack. At the request of the military leaders, he waited until the entire army had left the gorge, then from noon until evening he walked along the plain to the stream, where he settled down for the night. The battle that broke out in the morning ended quickly. A random gathering of Syrian-Palestinian squads under the command of numerous leaders could not resist the onslaught of the Egyptian army and fled to the city. But here the Egyptians, to the chagrin of the pharaoh, did not take advantage of the created situation. The enemy abandoned the camp and chariots, and the Egyptian army, busy with robbery, did not break into the city after the fugitives. It then took a seven-month siege for the city of Megiddo to surrender.

The pharaoh managed to deal with Kadesh no earlier than 20 years after that.

In those days, it was convenient to wage war only in the summer, when the weather was favorable and feeding the troops, carried out at the expense of other people's harvests, did not cause trouble. Campaigns in Palestine and Syria followed one after another: in 20 years, between the 22nd and 42nd years of his reign, Thutmose III made at least 15 of them, stubbornly securing what he had conquered and occupying more and more cities and regions. But the Egyptian army was poor at taking fortified cities. Often it departed with nothing, leaving everything around it devastated. This was the case with Kadesh, until finally, on one of the last campaigns, the Egyptians broke into it through a gap in the wall. The northern border of the campaigns of Thutmose III was, apparently, the city of Karkemish on the Euphrates, at the junction of Syria, Mesopotamia and Asia Minor.

The conquest of Syria could not but lead to a clash with the kingdom of Mitanni, located in Northern Mesopotamia. This kingdom, which then stood at the height of its power, laid claim to Syria. All Syrian states saw Mitanni as a stronghold in their struggle against the pharaoh. Having forced the Mitannian army to leave the Euphrates in the 33rd year of his reign, Thutmose III transported the ships built in the Phoenician city of Byblos by land and crossed the river. The Mitannians retreated further, and Thutmose sailed down the Euphrates, taking cities and destroying villages. A new defeat befell the power of Mitanni in the 35th year of the reign of Thutmose III. However, Mitanni continued to interfere in Syrian affairs even after this. Another 7 years later, in only three towns in the Kadesh region, which Thutmose III took in the 42nd year of his reign, there were over 700 Mitannians with fifty mines.

Thutmose III also fought in the south. The power that he created with such tenacity already stretched from the northern outskirts of Syria to the fourth cataracts of the Nile.

His successors did not go beyond the milestones achieved by Thutmose III. Ethiopia, Syria and Palestine paid annual tribute. Libya was also considered a tributary. Gifts arrived from the Southern Red Sea to the pharaoh. They were brought to the pharaoh and embassies from the Mediterranean islands. The Egyptian governor of Syria and Palestine - “chief of the northern countries” - under Thutmose III was considered his confidant on the islands of the Mediterranean Sea. The kings of Babylon, the Hittites, and Assyria, forced to reckon with the extremely increased importance of Egypt in international affairs, sent respectful gifts to the pharaoh, which he considered tribute. He re-appointed the defeated Syrian and Palestinian rulers to their cities with the condition of prompt payment of tribute. The children of these rulers were taken hostage to Thebes.

Quoted from: World History. Volume I. M., 1955, pp. 344-346.

Ancient East Struve (ed.) V.V.

Thutmose III's campaign in Asia

Thutmose III's campaign in Asia

In the fourth month of winter, the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III set out from the border fortress of Djaru and entered Palestine. On the fourth day of the first summer month of the twenty-third year of his reign (1503 BC) he arrived at the fortified city of Gaza. Here the pharaoh, settling in the palace of the local prince, ordered to call upon the officials who were entrusted with reconnaissance. The news was alarming. Almost all the cities of Palestine, Phenicia and Northern Syria rose up against Egypt. Vast Asian possessions from Iraza in the south to the distant lakes of the north and the mighty “backward flowing river” were lost. Local kings stopped recognizing the power of the Egyptian pharaoh and lost faith in his strength.

Thutmose was furious. He cursed his stepmother Hatshepsut, who died several months ago. He was sure that she was guilty of everything. For twenty-two years the power-hungry queen occupied the throne, not allowing her stepson to participate in government affairs. Wearing a double crown and tying up an artificial beard, she appeared in the throne room and solemnly received nobles and dignitaries.

Over time, the Asian kings began to act independently and stopped paying tribute to the Egyptian treasury. Thutmose had long sought to demonstrate his power and once again instill fear in his northern neighbors of Egyptian weapons, but during the life of his power-hungry stepmother there was nothing to think about this, so he looked forward to her death.

But the long-awaited day has come. Crowds of mourners announced the death of the queen. The luxurious gilded sarcophagus with her mummy was placed on a sled, and the bulls dragged it across the hot desert sand to the cliff-lined Valley of the Kings. The architect Hapuseneb and his assistants had long ago carved out four chambers and a narrow corridor of an underground tomb here.

Thutmose rejoiced. Now he will show foreigners the power of Egyptian weapons. The pharaoh calmly listened to the news of the alliance concluded by the king of the city of Kadesh with 60 kings of Palestine, Phenicia and Northern Syria “Were these the real rulers? - thought Thutmose. - After all, each of them ruled in his own city and surrounding district. Beet they hated each other, but only the fear of Egypt forced them to join forces. But how can they act in harmony? Anyone will envy their neighbor and rejoice at their losses in their hearts. Will they listen to the orders of a single military leader? No, everyone will give their own orders. There is nothing to fear from such enemies. The nobles, unaccustomed to military exploits during the years of peace, are cowards in vain.”

Having dismissed the messengers and spies, the king ordered four copper boards and the royal bow to be brought. He decided to try his skill again. The copper boards were placed in a row, at a short distance from each other. The king, slowly, took the huge compound bow and examined it complacently. The best gunsmiths did a great job. The strong wooden base was equipped with two skillfully carved grooves. Flexible plates of antelope horn were inserted into it, and the sinew of an ox was attached to the outside, and the whole thing was tightly wrapped with palm bast.

It is not easy to bend such a bow, but Thutmose had great strength and dexterity. With a habitual movement, he grabbed the bow, squeezed it with his strong fingers and instantly bent it. A taut, strong bowstring rang. Pharaoh took aim and fired. The arrow pierced three copper boards and got stuck in the fourth. With a satisfied smile, the king gave the order to fold the tents and set off.

Soon after, the Egyptian troops entered enemy territory, safely emerged from the mountain gorges onto the plain and approached Megiddo, where the enemy troops were fortified. Ahead stood the city walls and towers sparkling in the sun. The enemy army was nowhere to be seen. Scouts reported that the main enemy forces were concentrated to the south at Taanak.

Thutmose, moving in the front ranks of his army, had time to form it into battle formation. The chariots stretched out in a continuous line. A detachment of archers was moved forward. Behind were the infantry, followed by 500 selected chariots drawn by horses as fast as the wind. They were intended for the chase.

However, the enemy did not accept the battle that day. By evening the Egyptians set up camp. The military leaders posted sentries and walked around the warriors’ tents, announcing: “Get ready, arm yourself. A battle with the enemy is approaching. Be courageous."

The next morning the main enemy forces began to approach the camp. 3,000 chariots rushed forward. The bodies of some of them were decorated with gold and silver plates. The horses' harness also shone with gold and silver. The charioteers were dressed in heavy woolen multi-colored caftans, sleeveless, descending from shoulders to toes. Some had clumsy triangular wooden shells covered with leather to protect their chests and bellies. Some shot with arrows, others threw darts. A detachment of Egyptian archers moved forward and showered the enemies with a cloud of arrows. The enemy formation wavered. Some horses rushed forward, breaking the line, and came under flanking fire. The more timid turned their chariots back.

At this time, the Egyptian chariots had already lined up. The archers parted, opening the way for them. The Pharaoh's charioteers moved in a continuous avalanche. None of them moved forward. The horses, covered with light blue blankets, tied with red and yellow belts, moved at a measured trot. The charioteers, bending slightly and resting their knees on the front bar of the body, pulled their bows. The shield bearers standing nearby covered their commanders with small rectangular wooden shields rounded at the top. With their left hand they held the reins, holding back the fast horses. The warriors were dressed in long linen aprons. Their chests were protected by short leather and sometimes bronze armor. Arms and shoulders were completely bare.

The Egyptian chariots approached the enemy, and hundreds of charioteers simultaneously lowered their bowstrings on command. The enemy's battle formation was completely disrupted. Everything was mixed up: overturned bodies, corpses of horses and soldiers, charioteers who jumped off their chariots. The screams of military leaders and the groans of the wounded were heard everywhere.

Now the Egyptian infantry attacked the enemy chariots. In the left hand of the infantrymen there was a shield covered with leather, in the right - a bronze, sickle-shaped sword or a heavy spear. Soon the enemy's retreat turned into a stampede. Everyone tried to be the first to reach the fortress walls.

Thutmose ordered his commanders to pursue the enemy. He hoped to follow the fugitives into the fortress. But he failed to realize this intention. The victorious Egyptian army ceased to obey its commanders. The charioteers and infantrymen thought only of robbery. Some cut off the traces and jumped on captured horses, others broke the bodies of chariots, tearing off the gold and silver plates that decorated them, others finished off the wounded and tore off their expensive multi-colored clothes, untied belts decorated with gold buckles, and took away daggers in silver frames. Some tied up prisoners in pairs and drove them to the camp.

Pharaoh could not do anything. His army turned into a discordant, violent crowd. The king's voice was lost in the continuous hum of triumphant shouts, and Thutmose realized that he had to give in.

The retreating troops managed to reach the fortress. They shouted for the gates to be opened for them. But the ruler of Megiddo set up selected guards, ordering all the locks to be guarded. The fugitives were asked to climb the walls. Ropes, belts and just old clothes were lowered from above. The defeated warriors, throwing their weapons into the ditch, climbed up the sloping lower part of the wall, and then, having reached the steep upper part, made of smooth bricks, grabbed the edges of the lowered ropes. The warriors standing on the wall pulled them up.

If the Egyptians had not been distracted by the robbery, it is unlikely that any of the fugitives would have escaped.

Thutmose was unhappy. The victory did not please him. He was annoyed that he could not take advantage of the confusion that gripped the enemy and capture the city. Frowning his brows, the king looked around the fortifications of Megiddo. They seemed impregnable. A deep ditch bordered the fortress. The lower part of the wall was made of large stone blocks, and the upper part was made of flat bricks. Dozens of towers moved forward, sparkling with white battlements. Sharp shooters looked out from there, threatening to hit anyone who dared to approach.

At first, the Egyptians hoped to take the fortress by climbing its walls at night. By order of the pharaoh, wooden ladders were placed against the wall. But the besiegers did not manage to climb even to the middle of the wall. They were shot down and retreated with heavy losses.

Warriors carry the king on a stretcher (New Kingdom).

I had to start a siege. The enraged Thutmose ordered to cut down all the olive trees and fig trees in the surrounding gardens and build a wooden fence around the city. The posted guards did not let a single person through. The city, crowded with fugitives, had few food supplies. Hunger and disease began. Dead bodies were thrown into the ditch, and they rotted there under the hot rays of the summer sun - there was nowhere to bury the dead. An unbearable stench filled the city. Finally, messengers from the ruler of Megiddo came to Thutmose with a plea for mercy. The city gates opened and Egyptian soldiers rushed into the city. The robbery began. The Egyptians grabbed everything: furniture, clothes, jewelry, household utensils. Bound women and children, filling the air with sobs, were taken to the Egyptian camp. The captured warriors were shackled in bronze shackles and delivered to the pharaoh. He indicated which of them should be sent as a gift to the god Amon to Thebes to work on temple estates and workshops, and which should be given as a reward to distinguished military leaders and nobles.

The Egyptian army was returning home. The chariots were followed by wide carts loaded with booty, followed sadly by emaciated captives and female captives in dirty rags, barefoot, disheveled, with their hands twisted behind their backs.

The military leaders and charioteers were triumphant, but the ordinary infantrymen walked with their heads down, grumbling in a low voice.

Many Egyptian warriors cursed the ill-fated campaign and remembered with bitterness the murdered comrades buried in a foreign land. How many hardships the royal army had to endure - and all this so that the nobles and military leaders filled their houses with Asian gold and so that new crowds of foreign slaves began to work in the fields of the pharaoh and his entourage.

Many warriors had aching wounds that had not yet healed, others had scars burning on their backs and legs from recent blows with sticks, inflicted on the orders of picky military leaders. This was all they received as a reward for their victories.

From the book Geographical Discoveries author Khvorostukhina Svetlana Alexandrovna by Harold Lamb From the book Suleiman. Sultan of the East by Harold LambChapter 4. CAMPAIGNS TO ASIA The mystery of the poem Seven years ago, in June 1534, Suleiman was not yet bitter against the Europeans. His goals for Europe remained the same. But something drew him to Asia and made him essentially an Asian. After the fourteen years' war in Europe, Suleiman

From the book World History Uncensored. In cynical facts and titillating myths author Maria BaganovaGateway to Asia Alexander's first major victory was won at the Battle of the Granik River, called by contemporaries the “gateway to Asia.” Many were frightened by the depth of the river, the steepness and steepness of its opposite bank. Biographers write that Alexander threw himself into the river and led the army

From the book History of the Crusades author Michaud Joseph-FrancoisBOOK II FIRST CRUSADE: THROUGH EUROPE AND ASIA MINOR (1096-1097

From the book Geographical Discoveries author Zgurskaya Maria PavlovnaOn the way to Asia And it seems that in the world, as before, there are countries where no human foot has gone, where giants live in sunny groves and pearls shine in the clear water. And dwarfs and birds argue over nests, And the girls’ facial profiles are tender... As if not all the stars have been counted, How

From the book Scythians. "Invincible and Legendary" author Eliseev Mikhail BorisovichCampaigns in Asia The invasion of the Scythian tribes into the Northern Black Sea region and the expulsion of the Cimmerians who had ruled there for a long time was the prologue to their invasion of Asia. It was from this time - the 8th century. BC e. - they become known in the Ancient world as a formidable military force with which

From the book Crusades. Medieval Wars for the Holy Land by Asbridge ThomasTHROUGH ASIA MINOR Without Alexei's wise leadership, the Franks had to cope with many organizational and command difficulties. In essence, their army was a composite force, one large mass made up of many small units united by a common faith -

From the book Alexander the Great author Shifman Ilya SholeimovichChapter VI. CAMPAIGN TO CENTRAL ASIA AND INDIA Those few months that passed from the Battle of Gaugamela in the fall of 331 to the death of Darius III in the summer of 330 were probably the best times in Alexander’s short life. He destroyed the most powerful kingdom, conquered a great multitude

From the book History of the Far East. East and Southeast Asia by Crofts AlfredMigration to Southeast Asia From the earliest times, Chinese from Guangdong and Fujian settled throughout the southern regions. Their frugality, prosperity and isolation often caused hatred towards them. They were often persecuted, sometimes they were brutally dealt with

Chapter 7 Conquests of Thutmose III On the twenty-fifth day of the eighth month in the twenty-second year of his reign, Pharaoh Thutmose III passed the fortress of Charu (Sile), located on the eastern border of Egypt, “to repel those who attacked the borders of Egypt” and exterminate those who

From the book When Egypt Ruled the East. Five centuries BC author Steindorf GeorgChapter 8 The Golden Age: Successors of Thutmose III With the death of Thutmose III (about 1450 BC), his son Amenhotep II became the sole ruler of the Egyptian Empire (see plate 13). It is quite natural that Thutmose should have paid special attention to the education of the heir to the throne.

From the book Suleiman the Magnificent. The greatest sultan of the Ottoman Empire. 1520-1566 by Harold LambChapter 4 CAMPAIGNS TO ASIA The mystery of the poem Seven years ago, in June 1534, Suleiman was not yet bitter against the Europeans. His goals for Europe remained the same. But something drew him to Asia and made him essentially an Asian. After the fourteen years' war in Europe, Suleiman

From the book Egyptian Temples. Dwellings of the mysterious gods author Murray MargaretThe last Asian campaign of Thutmose III was necessary not to seize new lands, but to rein in the inhabitants of the already appropriated territories. The Syrian cities - primarily Tunip and Kadesh - were gripped by an uprising, which Thutmose urgently needed to suppress.

Thutmose led the army himself. First, the Egyptians decided to strike at Tunip, located to the north: this way the Pharaoh’s army could divide the rebellious cities and prevent them from acting together. In addition, Prince Tunipa was considered the most authoritative among the other city leaders, so the destruction of his city could cool down the rest of the rebels.

Burial chamber of Thutmose III

However, everything was so simple only in words. In fact, the siege of Tunip lasted several months. It ended in the fall, so enterprising Egyptian soldiers not only plundered the city, but also harvested crops in its surroundings. From now on, Kadesh was left without possible support from another strong Syrian city, which Thutmose decided to take advantage of.

Before approaching Kadesh, the pharaoh attacked three cities nearby. After this, it was the turn of Kadesh itself, a city that had just been recreated - nine years before the events described, Kadesh had already been attacked by the Egyptians, who literally razed it to the surface of the earth.

The ruler of the city decided to act with cunning: after waiting for the approach of the pharaoh's chariots, he sent one of his best horses towards them in order to cause confusion in their ranks. However, the idea was not crowned with success. As researchers learned from the story described in the tomb of Amenemheb, the pharaoh’s closest associate, Amenemheb himself, on his own two feet (!), rushed in pursuit of a frisky mare, caught her, pierced the horse’s stomach, cut off its tail and delivered it to Thutmose. Amenemheb then led a force that eventually took Kadesh by storm.

Statue of Thutmose III in the Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna)

The last Asian campaign of Thutmose III helped him completely defeat the rebels and strengthen the power of the Egyptians that already existed in the Syrian and Phoenician lands. The most important cities of the rebels - Tunip and Kadesh - were in ruins.

Thanks to Thutmose's numerous campaigns, Egypt grew to such a size that historians who study in detail the reign of this pharaoh even call him the “Napoleon of the Ancient World.” For example, archaeologist James Henry Breasted wrote: “His personality is more individual than that of any other king of Early Egypt, with the exception of Akhenaten... The genius manifested in the once humble priest makes us remember Alexander and Napoleon. Thutmose created the first true empire and is therefore the first world personality, the first world hero... His reign marks an era not only in Egypt, but throughout the entire East, known at that time. Never before in history has one man controlled the destinies of such a vast nation and given it such a centralized, strong and at the same time mobile character that for many years its influence was transferred with constant force to another continent, imprinted there like the blow of a skilled craftsman a heavy hammer on an anvil; It should be added that the hammer was forged by Thutmose himself.”

They made Egypt the first world power of antiquity.

Thutmose's first campaign

At the end of the 22nd year of Thutmose’s reign, on April 19, the Egyptian army, led by the pharaoh, set out from the border fortress of Charu (Greek Sile) on its first campaign in a long time. Nine days later (April 28), Thutmose celebrated his 23rd anniversary of accession to the throne in Gaza (Azzatu). On the 24th day of the campaign (May 14), the Egyptian army reached the foot of the Carmel ridge. According to Egyptian information, the entire country to the far north was engulfed in “an uprising against (that is, against) His Majesty.” On the other side of the mountains, in the Ezdraelon Valley, near the city of Megiddo, the allied army of the Syrians was waiting for the Egyptians. “Three hundred and thirty” Syro-Palestinian rulers, each with his army, decided to jointly block the path of the Egyptian king here. The head of the alliance was the ruler of Kadesh on the Orontes, who managed to rouse almost all of Syria-Palestine to fight Egypt.

Contrary to the persuasion of his companions to take a roundabout route, Thutmose, not wanting to be considered a coward among his enemies, went out to the enemy troops along the most difficult, but at least the shortest road, right through the gorge, where, if desired, the entire army of the Egyptians could easily be destroyed. This gorge was so narrow that the warriors and horses were forced to move along it in a column one at a time, one after another, with Thutmose himself leading his warriors. The enemy, who did not expect such a rapid advance of the Egyptians, did not have time to block the mountain gorges and the entire army of the pharaoh unhindered entered the plain in front of the city. Such strange behavior of the Syrians can be explained, perhaps, by the fear of leaving the camp near the city, behind whose walls they could hide in case of defeat.

In the battle that took place on the 26th day of the campaign (May 15), the rebel coalition was defeated, and the enemy warriors and their commanders fled to the protection of the walls of Megiddo, abandoning their horses, their chariots and their weapons. However, the gates of the city, in fear of the Egyptian soldiers, were locked and the city residents were forced to lift their fugitives onto the walls using tied clothes and ropes. Although both the king of Megiddo and the king of Kadesh were able to escape in this way, the son of the king of Kadesh was captured. The Egyptians, however, were unable to take advantage of the advantageous moment and take the city on the move, as they began collecting equipment and weapons abandoned by the enemy and plundering the camp they had abandoned. The Egyptians captured 3,400 captives, more than 900 chariots, more than 2,000 horses, royal property, and many livestock.

The rich booty captured by the Egyptians in an abandoned camp did not make any impression on the pharaoh - he addressed his soldiers with an inspiring speech, in which he proved the vital necessity of taking Megiddo: “If you had then taken the city, then I would have accomplished today (the rich offering) to Ra, because the leaders of each country who rebelled are locked in this city and because the captivity of Megiddo is like the capture of a thousand cities." The Egyptians were forced to go on a long siege, as a result of which Megiddo was surrounded by an Egyptian siege wall, called "Menkheperra (throne name of Thutmose III), who captured the plain of Asia." The siege of the city lasted quite a long time, as the Egyptians managed to harvest the crops in the surrounding fields. During the siege, the rulers of Syrian cities who had escaped encirclement in Megiddo arrived with tribute to Thutmose. “And so the rulers of this country crawled on their bellies to bow to the glory of His Majesty and beg breath into their nostrils (that is, to give them life), because the strength of his hand is great and his power is great. And Pharaoh forgave the foreign kings.”

During the first campaign, Thutmose also captured three cities in the Upper Rechenu: Inuama, Iniugasa and Hurenkara (the exact location of which is unknown), where more than two and a half thousand prisoners and enormous valuables in the form of precious metals and artificial things were captured. To top it all off, Thutmose founded a very strong fortress in the country of Remenen, he called “Men-kheper-Ra binding the barbarians,” and he uses the same rare word for “barbarians” that Hatshepsut applies to the Hyksos. From this it is clear that Thutmose considered his campaign against the Syrian princes as a continuation of the war with the Hyksos, begun by his ancestor Ahmose I. In light of this, it becomes clear why Manetho (as reported by Josephus) attributes the victory over the Hyksos to Thutmose III, whom he calls Misphragmuthosis ( from the throne name of Thutmose - Menkheperra).

After which Thutmose returned to Thebes, taking with him to Egypt as hostages the eldest sons of the kings, who expressed their submission to him. Thus, Thutmose III gave rise to a practice that the Egyptian administration used throughout the New Kingdom, since it both neutralized the possibility of anti-Egyptian unrest and ensured the loyalty of the local rulers of the cities of the Eastern Mediterranean, raised at the Egyptian court, to the power of the pharaoh. On the wall of the Third Pylon, an almost complete list of Syrian-Palestinian cities included in the alliance defeated by the pharaoh at Megiddo has been preserved.

In honor of his grandiose victory, Thutmose III organized three holidays in the capital, lasting 5 days. During these holidays, the pharaoh generously presented gifts to his military leaders and distinguished soldiers, as well as temples. In particular, during the main 11-day holiday dedicated to Amun, Opet, Thutmose III transferred to the temple of Amon three cities captured in Southern Phenicia, as well as vast possessions in Egypt itself, on which prisoners captured in Asia worked.

Fifth campaign

In the annals of Thutmose nothing was preserved about the 2nd, 3rd, 4th campaigns. Apparently, at this time Thutmose strengthened his power over the conquered territories. In the 29th year of his reign, Thutmose undertook his 5th campaign in Western Asia. By this time, the Syrian-Phoenician principalities had formed a new anti-Egyptian coalition, in which both the coastal Phoenician cities and the cities of Northern Syria began to play a significant role, among which Tunip emerged. On the other hand, Egypt, mobilizing both its own resources and the resources of the previously conquered regions of Palestine and Southern Syria (Khara and Lower Rechen), began to prepare for a new large military campaign in Western Asia. Realizing full well that Egypt would never be able to dominate Syria unless it had a strong foothold on the Phoenician coast, Thutmose III organized a fleet whose task was to conquer the cities of the Phoenician coast and protect the sea communications leading from Phenicia to Egypt. It is very possible that this fleet was commanded by precisely that old associate of not only Thutmose III, but also Thutmose II, the nobleman Nebamon, whom Thutmose III appointed as commander. The fifth campaign of Thutmose III was intended to isolate Kadesh from its strong allies on the Phoenician coast and thereby create favorable conditions for a complete blockade and further capture of Kadesh.

At present, it is not possible to identify the name of the city of Uardjet (Uarchet), which, as the chronicler indicates, was captured during this campaign. Judging by the further text of the Annals, one can think that Warjet was a fairly large Phoenician city, since, according to the chronicler, there was a “warehouse of sacrifices” and, obviously, in addition, the sanctuary of Amon-Horakhte, in which the pharaoh made sacrifices Theban supreme god. Apparently, this large Phoenician city was home to a fairly significant Egyptian colony. There is reason to believe that Uarchet was located relatively close to Tunip, and was part of the sphere of influence of this large city of Northern Syria, since the pharaoh, during the occupation of Uarchet, captured, along with other large booty, “the garrison of this enemy from Tunip, the prince of this city.” It is quite natural that the ruler of Tunip, economically and politically closely connected with the cities of the Phoenician coast, fearing an Egyptian invasion, sent auxiliary troops to Uarchet in order to jointly repel the onslaught of the Egyptian troops.

Egypt’s desire to capture not only the cities of the Phoenician coast, but also sea communications is emphasized in a passage from the Annals, which describes the capture by the Egyptians of “two ships equipped with their crew and loaded with all sorts of things, male and female slaves, copper, lead, white gold ( tin?) and all the beautiful things." Among the booty captured, the scribe noted slaves, female slaves, and metals as the most desirable values for the Egyptians.

On the way back, the Egyptian pharaoh devastated the large Phoenician city of Iartita with “its grain reserves, cutting down all its good trees.” The victories won by Egyptian troops over the enemy on the Phoenician coast gave a rich agricultural region into the hands of the Egyptians. According to the chronicler, the country of Jahi, occupied by Egyptian troops, abounded in gardens in which numerous fruit trees grew. The country was rich in grain and wine. Therefore, the Egyptian army was abundantly supplied with everything that it was supposed to receive during the campaign. In other words, the rich Phoenician coast was given over to the Egyptian army for plunder. Judging by the fact that in the description of the fifth campaign of Thutmose III in Western Asia, only the capture of one city of Warjet and the devastation of only the city of Iartitu are mentioned, the remaining cities of the Phoenician coast were not captured by the Egyptians. That is why the Egyptian scribe, describing the riches of the country of Jahi, lists only the orchards, wine and grain that fell into the hands of the Egyptian soldiers, which made it possible to supply the army with everything necessary. The listing of those offerings that were delivered to the pharaoh during this campaign is consistent with this. In this list of offerings, attention is drawn to a large number of large and small livestock, bread, grain, wheat, onions, “all the good fruits of this country, olive oil, honey, wine,” that is, mainly agricultural products. Other valuables are listed either in very small quantities (10 silver dishes) or in the most general form (copper, lead, lapis lazuli, green stone). Obviously, the entire local population hid with their valuables behind the strong walls of numerous Phoenician cities, which the Egyptian army could not occupy.

Thus, the most important result of the fifth campaign of Thutmose III was the capture of the country of Jahi (Phoenicia) - a rich agricultural region that provided several strongholds on the Phoenician coast. This bridgehead would allow larger military forces to be landed here during the next campaign with the aim of penetrating the Orontes Valley and capturing the most important cities of inner Syria. Undoubtedly, the mood of the Egyptian army must have been high, since, according to the chronicler,... With such naive words and very openly, the Egyptian scribe described the material security of the Egyptian army, which won a number of major victories in Phenicia.

Most likely, an interesting historical novel of a late edition, which tells about the capture of Joppa by the Egyptian commander Dzhuti (Tuti), belongs to this campaign. This Dzhuti allegedly called the king of Joppa and his soldiers to his camp for negotiations, and there he got them drunk. Meanwhile, he ordered one hundred Egyptian soldiers to be placed in huge wine pots and these pots to be taken to the city, supposedly the spoils of the king of the city. Of course, the hidden soldiers in the city jumped out of the pots and attacked the enemy; as a result, Joppa was taken. It is impossible not to see in this legend a motive in common with the story of the Trojan Horse.

Sixth campaign