Oratory has always been respected in Rome. It was believed that in a word, in peacetime, a Roman serves for the good of society in the same way as in wartime with a weapon in his hands.

One of these servants of society during the period of the republic, which replaced the aristocracy, was (106-43 BC).

He went down in the history of world culture as a brilliant, prominent statesman and public figure, philosopher and writer.

Born in 106 BC. e. in a family of provincials, which, thanks to its conservative principles, patience and hard work, created the Roman Republic, remaining for a long time the “core” of the nation.

These were peasant landowners who enjoyed respect and sufficient influence in the district, even having some connections in the capital itself. But one of his ancestors, presumably, was from simple peasants - hence this plebeian nickname for the future great orator - Cicero (pea genus). But, despite this, Mark was proud of this name and promised his scoffers to glorify it on a par with the aristocratic names of Scaurov and Catulli

(E. N. Orlov. “Marcus Tullius Cicero. His life and work").

It must be said that his grandfather was a true conservative who was afraid of everything new. He was especially fearful of the influence of Greek culture on Roman culture, which took place at that time. And his fears were not unfounded, for his son - Mark's father - was a man of a completely different character - quiet, thoughtful and easily influenced. So, under the influence of books and conversations, he began to feel burdened by his small-scale life and dreamed of breaking out of it. His wife sympathized with him in this, and when their children, Marcus Tullius and Quintus, grew up and reached school age, they left the village and moved to the city so that the children could receive a decent education.

As we noted above, at that time the dominance of Greek culture in Rome began. All teachers were Greek. And, naturally, Cicero received a Greek education.

Cicero began his professional activity as a lawyer in criminal and civil cases at the age of 27. But history, unfortunately, has not preserved documentary evidence of his first performances.

His first speech that reached the modern reader was the speech “ In defense of Russia", accused of murdering his father. The success of this speech marked the beginning of his oratorical fame.

Cicero achieved even greater popularity after speaking on the case of Verres, the former governor of Sicily.

In 70 BC. e., filing a claim of extortion against Verres, the Sicilians turned to Cicero for help, remembering his oratorical talents. The praetors, bribed by Verres, delayed the proceedings to such an extent that they did not leave Cicero time to deliver an indictment before the start of the holidays. However, he so competently and deftly proved to the judges the guilt of the governor, accused of bribery, outright robbery and murder of Sicilians and Roman citizens, that his speech decided the matter, and Verres was sent into exile.

After this speech, Cicero was at the height of his glory and, not content with the victory he had won, issued all five speeches that he intended to make if Verres brought the matter to a second instance.

In 63 BC. e. Cicero is elected to the highest position of consul and makes several speeches against Lucius Sergius Catilina - the head of the conspiracy in Ancient Rome, which received its name from him.

Later, Cicero will deliver a panegyric about granting imperia (full executive power) to Gnaeus Pompey and the Senate will agree to the dictatorship, bowing its head before the great orator and great commander.

Its final chord was the fourteen philippics against the triumvir Mark Antony. Cicero himself on December 7, 43 BC. fell victim to intrigue and proscription, paying for the “elasticity” of his political views.

This, in a nutshell, is the social life of a well-known person.

If you need to write, for example, a paper about this political figure and this material is not enough for research, you can order the writing of a term paper or any work on the website 5orka.ru. And you are guaranteed an “A”!

That's all for now!

After the death of Caesar, speaking for the republic as the leader of the Senate party, he energetically attacked Antony, and he achieved the inclusion of Cicero’s name in the proscription lists. Persons included in these lists were declared outlaws, and anyone who killed or betrayed these people received a reward, their property was confiscated, and slaves received freedom.

Cicero learned that he was outlawed while he was with his brother Quintus on his estate near Tusculum. “...They decided,” writes Plutarch, “to go to Astura, the seaside estate of Cicero, and from there to sail to Macedonia to Brutus, for there were already rumors that he had large forces. They set off, overwhelmed with grief, in a stretcher; stopping at path and, placing the stretcher side by side, they bitterly complained to each other. Quintus was especially worried, thinking about their helplessness, for, said Quintus, he had not taken anything with him, and Cicero had a meager supply. So, it would be better if Cicero will outstrip him in flight, and he will catch up with him, taking what he needs from the house. So they decided, and then they embraced goodbye and parted in tears. And so, a few days later. Quintus, given out by slaves to the people who were looking for him, was killed along with son. And Cicero, brought to Astura and finding a ship there, immediately boarded it and sailed, taking advantage of a fair wind, to Circe.

The helmsmen wanted to immediately sail from there, but Cicero, either because he was afraid of the sea or had not yet completely lost faith in Caesar, got off the ship and walked 100 stades, as if heading to Rome, and then, in confusion, again changed his mind and went down to the sea in Astra. Here he spent the night in terrible thoughts about his hopeless situation, so that it even occurred to him to secretly sneak into Caesar’s house and, committing suicide at his hearth, bring the spirit of vengeance upon him; and the fear of torment distracted him from this step. And again grasping at other disorderly plans he had come up with, he allowed his slaves to take him by sea to Caieta, where he had an estate - a pleasant refuge in the summer, when the trade winds blow so caressingly. In this place there is also a small temple of Apollo, rising above the sea. While Cicero's ship was rowing towards the shore, a flock of ravens, rising from the temple, flew towards him, cawing. Having settled along the shore, some of them continued to croak, others pecked at the fastenings of the gear, and this seemed to everyone a bad omen.

So, Cicero went ashore and, entering his villa, lay down to rest. Many crows sat on the window, emitting loud cries, and one of them, flying onto the bed, began to gradually pull off the cloak with which he had covered himself from Cicero’s face. And the slaves, seeing this, reproachfully asked themselves whether they would really wait until they witnessed the murder of their master and protected him, while the animals helped him and took care of him in his undeserved misfortune. Acting either by requests or by compulsion, they carried him in a stretcher to the sea.

At the same time, the murderers appeared, the centurion Herennius and the military tribune Popillius, whom Cicero had once defended in a trial on charges of parricide; There were also servants with them. Finding the doors locked, they forced them open. Cicero was not there, and the people who were in the house claimed that they had not seen him. Then, they say, a certain young man, a freedman of Quintus, Cicero’s brother, named Philologist, educated by Cicero in the studies of literature and science, pointed the tribune at people with stretchers, along densely planted, shady paths heading towards the sea. The tribune, taking several people with him, ran around the garden to the exit; Cicero, seeing Herennius running along the paths, ordered the slaves to place the stretcher right there, and he himself, as was his habit, holding his chin with his left hand, stubbornly looked at the murderers; his neglected appearance, overgrown hair and face, worn out from care, inspired regret, so that almost all those present covered their faces while Herennius killed him. He stuck his neck out of the stretcher and was stabbed to death.

He died at the age of sixty-four. Then Herennius, following the orders of Antony, cut off Cicero's head and hands, with which he wrote the Philippics: Cicero himself called his speeches against Antony the Philippics.

The same Brutus who took part in the murder of Caesar.

That is, in Antony; The name Caesar was included in the title of the supreme rulers of the Roman Empire.

CICERO (Cicero) Marcus Tullius (106-43 BC), Roman politician, orator and writer. Supporter of the republican system. Of the works, 58 judicial and political speeches, 19 treatises on rhetoric, politics, philosophy and more than 800 letters have been preserved. The works of Cicero are a source of information about the era of civil wars in Rome.

CICERO Marcus Tullius(Cicero Marcus Tullius) (January 3, 106, Arpina - December 7, 43 BC, near Caieta, now Gaeta), Roman orator, eloquence theorist and philosopher, statesman, poet, writer and translator. The surviving heritage consists of speeches, treatises on the theory of eloquence, philosophical works, letters and poetic passages.

Biographical information

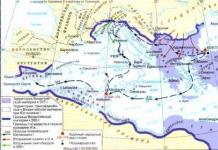

A native of the town of Arpina (120 km south-east of Rome) from a family of horsemen, Cicero has lived in Rome since 90, studying eloquence from the jurist Mucius Scaevola Augur. In 76 he was elected quaestor and performed magistrate duties in the province of Sicily. As a quaestor, having completed his magistracy, he becomes a member of the Senate and goes through all stages of the Senate career: at 69 - aedile, 66 - praetor, 63 - consul. As consul, he suppressed the anti-Senate conspiracy of Catiline, receiving, in recognition of his services, the honorary title of Father of the Fatherland (for the first time in the history of Rome, awarded not for military exploits). In 50-51 - governor of the province of Cilicia in Asia Minor.

Beginning at 81 and throughout his life, he gave political and judicial speeches with constant success, gaining a reputation as the greatest orator of his time. The most famous speeches can be named: “In defense of Roscius from Ameria” (80), speeches against Verres (70), “In defense of the poet Archia” (62), four speeches against Catiline (63), “On the answer haruspices", "On the consular provinces", in defense of Sestius (all three - 56), thirteen speeches against Mark Antony (the so-called Philippics) - 44 and 43.

Since the mid-50s. Cicero is increasingly immersed in the theory of state and law and the theory of eloquence: “On the State” (53), “On the Orator” (52), “On Laws” (52). After the civil war of 49-47 (Cicero joined the Senate party of Gnaeus Pompey) and the establishment of the dictatorship of Caesar, Cicero lived mainly outside Rome in his rural villas until the end of 44. These years are characterized by a special rise in Cicero's creative activity. In addition to continuing to work on the theory and history of eloquence (“Brutus”, “Orator”, “On the best form of orators”, all three - 46), he creates the main works on philosophy, among which the most important and famous are “Hortensius” (45 AD). ; preserved in numerous extracts and fragments), “Teachings of the Academicians” and “Tusculan Conversations” (all - 45); By 44 there are two works of a special genre - “Cato, or On Old Age” and “Laelius, or On Friendship”, where Cicero created idealized and on the verge of artistic depiction images of the great Romans of the previous century who were especially spiritually close to him - Cato Censorius, Scipio Emiliana, Gaia Lelia.

In March 44 was killed; in December, Cicero returns to Rome to try to convince the Senate to protect the republican system from the heirs of Caesar's dictatorship - the triumvirs Octavian, Antony and Lepidus. His speeches and actions were unsuccessful. At the insistence of Anthony, his name was included in the proscription lists, and on December 7, 43, Cicero was killed.

Basic problems of creativity

Basic problems of creativity

Origin from a small Italian municipality, where the Tullian family had been rooted since time immemorial, was the biographical basis for the doctrine of “two homelands” developed by Cicero in the treatises “On the Orator” (I, 44) and “On the Laws” (II, 5): Every Roman citizen has two homelands - by place of birth and by citizenship, and “the homeland that gave birth to us is no less dear to us than the one that received us.” Here a fundamental fact of the history and culture of the ancient world was reflected: no matter how extensive the later state formations, monarchies or empires, the socially and psychologically real initial unit of social life remained the city-state - the civil community - that continued to live within them (“On Responsibilities” I, 53). Therefore, the Republic of Rome, which by the time of Cicero covered vast territories, was not exhausted for him by its military-political and state-legal content. He saw in it a form of life, an intensely experienced immediate value, and considered its basis to be the solidarity of citizens, the ability of everyone, having understood the interests of the community and the state, to act in accordance with them. The whole point was to correctly explain these interests to them, prove and convince them with the power of words - eloquence was for Cicero a form of spiritual self-realization, a guarantee of the social dignity of a citizen, the political and spiritual greatness of Rome (Brutus, 1-2; 7).

Two paths led to the heights of eloquence. One consisted of serving the state and its interests with words on the basis of selfless devotion to them, civic valor (virtus) and extensive knowledge of politics, law, philosophy (On finding material I, 2; On the speaker III, 76); another way was to master formal techniques that allowed the speaker to convince any audience to make the decision he needed (On finding material I, 2-5; On the speaker 158; speech in defense of Cluentius 139); the art of this latter kind was designated in Rome by the term rhetoric, which was Greek in origin. Cicero’s desire to combine high spiritual content with practical techniques in teaching an orator, as in any teaching in general, ensured him an important place in the theory and history of pedagogy. However, in the specific conditions of Ancient Rome, both these sides of the matter became less and less compatible: the crisis of the republic in the 1st century, which led to its replacement by the empire, was precisely that its political practice was increasingly focused on the interests of only the ruling elite of the city of Rome and came into increasingly sharp conflict with the interests of the development of the state as a whole and with its conservative value system. The moral perspective, on the one hand, and ensuring the immediate interests, be it of the state leadership, the client in court or one’s own, on the other, were in constant and deepening contradiction, and the unity of virtus and political - even broader: life - practice was increasingly revealed as a feature not of the real, but of the ideal Rome, as its artistic and philosophical image.

All the key moments of Cicero’s activity and his work, as well as the perception of him by subsequent centuries, are connected with this contradiction.

The moral code of the Roman Republic was based on conservative loyalty to the traditions of the community, on legality and right, and respect for the success achieved on their basis. Cicero strove to be faithful to this system of norms and, as a statesman and orator, repeatedly followed it. But faithful to the code of the Senate nobility, which more and more clearly sought - and with great success - to use this code in its own favor, Cicero just as often turned to purely rhetorical techniques and built speeches in defense not of moral norms, but of profit: see agreement to speak in two years before the conspiracy of Catiline in his own defense, a speech in defense of the undeniably criminal Gaius Rabirius or Annius Milo and others. This inconsistency was blamed on him and was considered as his fundamental feature by the humanists of the Renaissance and learned historians of the 19th century (T. Mommsen and his school).

Against the background of the practical activities of a politician and a judicial orator in Cicero, the need to overcome this fundamental contradiction lived and grew. One of the ways was for Cicero to constantly enrich his theory of eloquence with Greek philosophy, and the Roman tradition and value system as a whole with the spiritual experience of Hellas. He lived for long periods in Greece three times, translated a lot from Greek, constantly refers to Greek thinkers, calls him “our deity” (Letters to Atticus IV, 16), sees the dignity of a Roman magistrate in his ability to be guided in his activities by the practical interests of the Senate republic, but in at the same time and philosophy (letter to Cato, January 50), “and since the meaning and teaching of all the sciences that show a person the right path in life is contained in the mastery of that wisdom, which the Greeks call philosophy, then its I considered it necessary to present it in Latin” (Tusculan Conversations I, 1). The content of Cicero's works in the 40s. politics and eloquence of a special kind become - saturated with philosophy and law, images of Rome and the Romans of bygone times become, summing up in an idealized form the spiritual traditions of Greco-Roman antiquity. During the years of civil war and dictatorship, this ideological position was finally revealed as a norm of culture independent of life practice (Letters to Atticus IX, 4, 1 and 3; “Cato” 85; “Laelius” 99 and 16), but called upon to live and correct it. This side of Cicero’s thought and activity became in the 20th century. basis in the assessment and study of his heritage (after the appearance of a collective article about him in the “Real Encyclopedia for the Study of Classical Antiquity” by Pauli-Wissow (1939) and the works based on it.

Marcus Tullius Cicero... There are not enough epithets of the Russian language to describe the great statesman, the amazing sage.

About achievements

Thanks to the works that Marcus Tullius Cicero wrote - about the state, about the policies of emperors and kings, modern researchers can accurately describe the events of the past.

The great Roman sage preached philosophy in its special interpretation, namely, he introduced a huge number of new concepts. For example, a definition is a set of explanatory characteristics of a subject; progress - ascension, advancement, and so on.

The beginning of the era of stoicism

One of the most prominent representatives of the philosophy of Stoicism was Marcus Tullius Cicero. The speaker talked a lot about how the only source of happiness is nothing other than human virtue. In his understanding of virtue, Cicero invested such personality qualities as wisdom, courage, justice, and moderation in all endeavors.

Thus, through his teachings and thoughts, the ancient Roman sage tried to understand what the solution to the problem of confrontation between personal gain and moral duty was. Understanding this issue, Marcus Tullius Cicero came to the conclusion about the need to study practical philosophy.

Culture of Ancient Rome: aesthetics, beauty and eloquence

The moral-cognitive position of the philosopher included an inextricable unity between eloquence and the highly moral moral content of the individual. Based on the presence of these personal qualities, according to Cicero, he could have turned out to be quite a good speaker.

The development of Roman philosophy was based on a solid foundation of ancient Greek culture. Marcus Tullius Cicero spoke about comprehending the truth about the concept of its deep issues, which depend on genuine eloquence - every self-respecting Roman should have it. Learning the art of speech is something that was necessary for the society of Ancient Rome.

Along with eloquence, the philosopher emphasized the importance of moral beauty. “It is impossible to achieve deep thoughts and true knowledge if your thoughts pursue base goals,” said Cicero.

Literary heritage

In addition to deep reasoning, Marcus Tullius Cicero left a rich literary heritage. It is impossible to describe the volume of all the writings, speeches and letters; many were recognized during his lifetime, many were published only several centuries later. Most of the works are addressed to specific individuals - the speaker's friends Titus Pomponius and Marcus Tullius Tiron. In total, about 57 manuscripts have survived; according to unofficial data, the same number were lost.

Several works of philosophical content are a huge world heritage: the books “On the Orator”, “The Orator” and “Brutus”. Here Cicero discusses the ideal methods of teaching and instilling the skills of oratory, and also thinks through questions about the individual style of the speaker.

It is worth especially noting the works of political content. The most famous works today are “On the State” and “On Laws”. Here Marcus Tullius Cicero, whose biography contains management experience, discusses the structure of an ideal state. The ideas that he laid down in each of his works were realized through the Roman constitution: a successful combination of such bodies as the senate, consulate and popular assembly.

For writing later works, Cicero used as the main one, through which he tried to find solutions to the problems of ancient Greek philosophers. A lot of information can be gleaned from the philosopher’s correspondence that was addressed to famous personalities. In total, about 4 collections of letters have survived.

The value of philosophical teachings in the future

Thanks to the philosopher of the Roman era, classical Latin prose was born, imbued with the wisdom of oratory, as well as deep philosophical thoughts. If initially little attention was paid to this literary direction, then in subsequent centuries it was considered exemplary and the most correct.

After his death, Cicero was compared with a huge number of orators, among whom was the famous Demosthenes, a representative of Greek culture and oratory. More than 100 years later, this comparison is one of the most controversial and interesting.

The philosophical teachings of Marcus Tullius were valued not only in the modern era, but also in the fastidious Middle Ages, as well as in the vibrant modern era, where recognition of the views of the past as relevant was rare. Cicero believed that the main criterion of a person’s value is his education, which can only be gifted by Greek culture. He was the first to use the term humanitas to designate a well-mannered, well-read and generally educated person with the proper moral qualities.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) is an outstanding figure of Ancient Rome. He was a philosopher, politician, lawyer, brilliant orator, political theorist, and at the peak of his career became consul. Thanks to his principles and devotion to the republican system, he made many powerful enemies. Among them are Gaius Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. He was declared an enemy of the state and executed, but the memory of this amazing man has survived centuries. Nowadays, Cicero is known and remembered by everyone, and his influence on European culture exceeds that of any other prominent historical figure.

Brief biography of Cicero

Cicero was born in January 106 BC. e. in the city of Arpinum (100 km southeast of Rome) in the family of a Roman horseman. His father was a wealthy man and well connected in Rome. Little is known about Helvia's mother. She was an ordinary wife of a wealthy Roman citizen. She was responsible for running the household and was considered a thrifty housewife. Mark had a younger brother, Quintus Tullius Cicero. He was born in 103 or 102 BC. e. The brothers were friends all their lives and both were killed in 43 BC. e. by decision of the second triumvirate.

Mark and Quint's father became disabled at an early age, and therefore was unable to make a political career. He decided to embody his unfulfilled dreams in his sons. In 91 BC. e. he moved with his family to Rome so that the boys would be in the thick of political events and receive a good education.

At that time, culture meant knowledge of not only Latin, but also Greek. And Mark, having studied this language, became acquainted with the works of ancient Greek philosophers, poets and historians. In addition, he translated many ancient Greek works into Latin for a wide audience. It was his education that made it possible to get into the traditional circle of the Roman elite.

According to Plutarch, it is known that Cicero was an extremely capable student. This gave him the opportunity to study Roman law under Quintus Mucius Scaevola himself (one of the most popular lawyers in Rome). There he met and became friends with fellow students Servius Sulpicius Rufus and Titus Pomponius. The first became a brilliant lawyer, and Mark considered him superior to himself in knowledge of legal issues. The second's sister married Quintus, and Titus, according to Cicero himself, became his second brother. He corresponded with both friends all his life.

At that time, there were certain rules for people seeking to make a career. They had to go through military and political positions. As a result of this, Marcus Tullius Cicero in 90-88. BC e. served in the army of Sulla, who in his beliefs was the predecessor of the Roman emperors. During his reign, the Allied War was unleashed, and during this period Mark realized that he had no taste for military life. He is an intellectual and gravitates towards philosophy, law and rhetoric.

Cicero began his career as a lawyer around 83-81. BC e. His defense brought him fame in 80 BC. e. Sextus Roscius, accused of parricide. A recording of Cicero's speech at this trial has survived to this day. At that time, parricide was considered one of the most terrible crimes, and Roscius' accusers were Sulla's favorites. Therefore, the defense of the young lawyer was an indirect challenge to the dictator.

Russia was acquitted, and Mark in 79 BC. e. left for Athens and then to the island of Rhodes, fearing the wrath of Sulla. There he continued to study philosophy and improve his oratory. He was so successful in this latter activity that he was subsequently considered the second orator of the Ancient World after Demosthenes.

Personal life

In 78 BC. e. Sulla died and Mark returned to Rome. In the “eternal city” he found himself a rich wife named Terence (98 BC - 6 AD). Everyone said it was a marriage of convenience. But it is well known that arranged marriages are the strongest. Young Cicero needed money, and his young wife needed a husband with a promising political career. The interests of the young people coincided, and they lived together for 30 years. At the time of their wedding, Cicero was 27 years old and Terence 18 years old. Plutarch characterized Terence as a strong-willed and purposeful woman who took an active part in her husband’s career.

In 45 BC. e., shortly before his death, Marcus Tullius Cicero became infatuated with a young girl named Publilia, whose guardian he was. A divorce from his wife followed, but the relationship with the young creature did not last long. But the famous orator loved his daughter Tullia (79-45 BC) very much. When she suddenly fell ill and died, her father was plunged into a state of deep sorrow, and even his enemies sympathized with him.

But the son Mark, born in 65 BC. e., outlived his father by many years. The great orator himself wanted his son to become a philosopher, but he gravitated towards military service. As a young man, he joined the army of Pompey, and after the defeat of the latter he was pardoned by Caesar. The father sent his son to Athens to learn the basics of philosophy, but the son, having gotten rid of the watchful eye of his father, began to drink and have fun.

In 43 BC. e., after the murder of his father, he joined the rebellious politicians Cassius and Brutus. But at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC. e. the rebels were defeated. Octavian pardoned Cicero's son and subsequently made him an augur. In 30 BC. e. he was nominated for the post of consul. It was Cicero’s son who announced in the Senate the death of Mark Antony, who was the main culprit in the execution of the great orator. Thus, the son indirectly avenged his father's death. Later he was appointed proconsul to Syria and Phrygia (a Roman province in Asia). The year of death of this person is unknown.

Cicero's political career

Cicero's political career began in 75 BC. e. At the age of 31 he became a quaestor, then at the age of 37 in 69 BC. e. was appointed aedile, and at the age of 40 in 66 BC. e. became praetor. At the age of 43 in 63 BC. e. Mark was elected consul. This was the highest elected office in the Roman Republic.

One of the losing candidates was Lucius Sergius Catilina. He put forward his candidacy for the following year, but realizing that he had no chance, he began to prepare a plot to seize power. Cicero learned of the impending conspiracy and began to denounce Lucius in his speeches. A total of 4 speeches were made against Catiline. All of them were examples of oratory. Catiline fled from Rome, and his like-minded people were arrested, taken to prison and strangled there.

In 60 BC. e. Gaius Julius Caesar invited Cicero to become the fourth in an already existing partnership with Pompey and Crassus. But Mark refused the offer, declaring his loyalty to the Republic and democracy. After his refusal, Caesar, Pompey and Crassus formed the first triumvirate, the goal of which was to seize power.

Marcus Tullius Cicero gives a speech in the Senate

However, the refusal to ally with the powers that be turned out to be disastrous for Mark. He was opposed by such a powerful opponent as the people's tribune Publius Clodius. At one time, Cicero testified against him in court, which was the reason for the hostility. In 58 BC. e. Clodius achieved the adoption of a law that condemned to exile an official who executed a citizen of the Roman Republic without trial. There was a moment in Mark’s biography when he participated in the murder of like-minded people of Catiline. They were strangled without trial, although they were citizens of Rome.

Nobody wanted to help Marcus Tullius Cicero in this sensitive matter. And he was forced to go into exile, leaving for Thessalonica (Ancient Greece) at the end of May 58 BC. e. At the same time, the real estate and property of the great speaker were confiscated. But the exile lasted just over a year. The newly elected tribune of the people, Titus Annius Milo, who was a supporter of Pompey, called on the Senate to vote for the return of Cicero. Everyone voted in favor, only Clodius was against it. And already in August 57 BC. e. the returning speaker was greeted by a cheering crowd.

End of political career and death

In the “eternal city” Marcus Tullius found himself in a difficult situation. He owed his return to Pompey, and, therefore, had to support the triumvirate, ignoring the interests of the Republic and democracy. This contradicted Cicero's views, and he stopped engaging in politics, concentrating on legal and literary activities. But it was not so easy to escape from the world of intrigue and struggle for power.

In 51 BC. e. the great orator was appointed proconsul to Cilicia (Asia Minor), and he went to the distant land with the greatest reluctance. There he conscientiously performed his duties from May 51 BC. e. to November 50 BC. e. Arriving at his place of duty, the new proconsul discovered that most of the state property was being stolen. The theft was stopped, and the money went to the needs of the city. He managed to defeat the robber tribes that settled on Mount Amanus, and for this the legionnaires began to greet him as emperor.

Upon returning to Rome, Cicero again found himself in a difficult situation. A struggle began between Pompey and Julius Caesar. Marcus Tullius took the side of Pompey, seeing in him a defender of the Senate and republican traditions. At the same time, he avoided open opposition to Caesar and tried to reconcile political opponents, realizing that if a civil war broke out, it would end in tyranny.

In the end, Marcus Tullius had to make a choice and join Pompey. But he was defeated at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC. e. and fled to Egypt. After this, the great orator came to Rome, and Caesar forgave him. Cicero had no choice but to adapt to the new situation, hoping that Caesar would revive the Republic and its democratic institutions. But the murder of Caesar in 44 BC came as a complete surprise to him. e.

Marcus Tullius Cicero was not among the conspirators, but they treated him with sympathy. Immediately after killing the dictator, Marcus Junius Brutus raised his bloody dagger and shouted Cicero's name, asking him to restore the Republic. The great orator became a popular leader during a period of instability, but republican principles did not triumph.

In Rome, Julius Caesar's closest associate, Mark Antony, quickly gained strength. He became the unofficial executor of the public will of the murdered dictator. Brutus and Cassius fled Italy, and Cicero was left alone with the man who hated him. The reason for the hatred was that during the suppression of Catiline's conspiracy, Anthony's stepfather was killed without trial. Caesar's associate blamed Marcus Tullius primarily for this death.

Soon there was an open conflict between Anthony and Cicero. This happened at a meeting of the Senate on September 2, 44 BC. e. The great orator made a speech denouncing Caesar's associate. He called it “philippic,” alluding to Demosthenes’ speech against the policies of Philip of Macedon. Subsequently, he pronounced 3 more “philippics” and called on the Senate to name Anthony an enemy of the state. The authority of the great orator was so high that many authoritative people united around him.

Marcus Tullius also enlisted the support of Octavian, who was Caesar's adopted son. He was considered the heir of the murdered dictator and initially supported Cicero. As a result of all this, Mark Antony left Rome, and the great orator became the head of the Republic. But politics is an unpredictable thing. In the month of October 43 BC. e. Octavian, Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus created the second triumvirate. It was approved by the People's Assembly of Rome, and this union received the status of a legal body.

After this, the great orator himself and all his supporters were ranked among the enemies of the state. Legions of triumvirs entered Rome, and Cicero had no choice but to flee. He was caught on December 7, 43 BC. e., when slaves carried the great orator from his villa to the ship that was supposed to sail to Macedonia.

Seeing his pursuers approaching, Marcus Tullius ordered his slaves to place the palanquin on the ground and waited until the centurion Gerenius and the tribune Popilius approached him. He said: “There is nothing special about you wanting to kill me, but do it properly.” After these words, the great orator bowed his head and made it clear that he was ready for death.

According to Plutarch, the centurion Gerenius cut off Cicero's head and hands, with which he wrote the philippics. The severed body parts were brought to Rome by order of Mark Antony and nailed to the forum platform from which the speakers spoke. According to the Greek historian Dio Cassius, Antony's wife Fulvia pulled the tongue out of the mouth of the death's head and stuck several pins into it, thereby emphasizing her hatred of the great orator of Ancient Rome.

This is how one of the most outstanding people of antiquity, Marcus Tullius Cicero, ended his life. Contemporaries characterized him as an honest and deeply decent person. He advocated democracy, but lived at a time when the Roman Republic began to steadily transform into an empire. This process did not find understanding in the soul of the great orator, and he became a victim of political intrigue, paying for his ideas and views with his life.